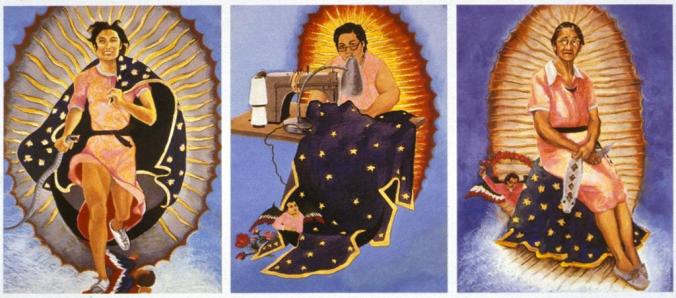

The Guadalupe Series, by Yolanda Lopez. 1978. (Source)

Recently, Fr. James Martin SJ posted these three images on his Facebook page with the following caption: “Mira! Look at these beautiful images of Our Lady of Guadalupe, reimagined as contemporary women. Remember that Our Lady lived a real life in Nazareth.” He then included a link to a website about the artist, Yolanda Lopez.

When some of his followers responded negatively, Fr. Martin wrote the following comment, quoted in full:

Some of the comments on this post are truly ridiculous. Yes, there is one beautiful and holy image, given by Our Lady, to Juan Diego at Tepeyac (which I posted earlier today). But reimagining Our Lady has been done since the earliest days of the church. Most of the images we are used to are images in which she was imagined as a woman of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, in which the Blessed Mother is dressed in contemporary dress (not as a woman in first-century Galilee would have been dressed). The artist, as I see it, was trying to remind us that Mary (Our Lady) was a real woman. And that the artist sees her in those around her, especially in Mexican women. People need really need to calm down, stop picking apart her art, and stop using words like heresy and blasphemy. Of course you don’t have to like it (art is very subjective of course) but you also don’t have to hurl accusations. I’m as devoted to Our Lady as you are, and if I didn’t like something I’d just nod and move on. Not everything has to end up as a crusade.

There are all kinds of problems with the Jesuit’s post, from his Mariology to his aesthetic philosophy. And while he may have been annoyed that his followers dared to turn his humble offering into the occasion of “a crusade,” I’m afraid that he really leaves us no choice. His post is a scandal for a number of reasons.

It bears mentioning that Fr. Martin is right to suggest that our images of Mary are always shaped in part by culture. But there is a difference between the unconscious ethnocentrism of the Medieval imagination and deliberate efforts to portray Mary or Jesus as something other than what they were. If an artist is (a) going to go down that path, and (b) do so as a well-formed Catholic, then there are a few principles that he should probably stick to along the way.

First, all changes to the subject’s probable historic appearance or culture should serve to illustrate the subject’s deeper identity as well as to magnify his or her glory.

African Madonna, Studio Muti, South Africa. c. 2013. (Source)

A good example of this kind of art is African Madonna, by Studio Muti. This Marian image works well both because it is constructed in dialogue with the tradition of Christian art – specifically, processional statues of the Virgin – and it powerfully captures the dignity of the sacred subject. We could probably guess who this is, even without some of the ordinary symbols of the Mother of God to aid us.

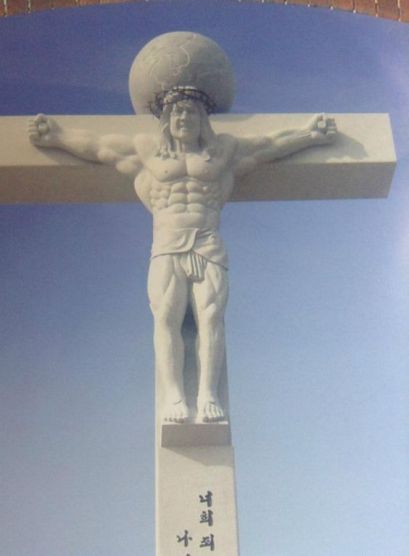

Second, kitsch should be avoided. If the work is devotional or liturgical in any sense (that is, destined for a worship space or context of veneration), then gimmicks become flatly inappropriate. Need we turn to the infamous “Korean Jesus” of 21 Jump Street?

Just….why? (Source)

Finally, these kinds of renditions should ordinarily come from the people themselves. Unfortunately, much of it has been produced by well-meaning white liberals like Br. Robert Lentz OFM or Fr. John Giuliani.

Navaho Madonna, Br. Robert Lentz OFM. (Source)

When consciously non-white or non-Western depictions of Christ and the Virgin are created by white and Western artists, the danger of cultural appropriation is at its highest. See Lentz’s canned reduction of Navajo culture in his artist’s statement for the above “icon.” See also Fr. Giuliani’s statement that he “intends that his work celebrate the soul of the Native American as the original spiritual presence on this continent, thus rendering his images with another dimension of the Christian Faith.” One detects in these images a dollop of self-important White Savior mentality beneath the breathless exoticism. It’s all very patronizing.

A much better example comes from Daniel Mitsui, who draws upon the artistic traditions of his own Japanese heritage to lovingly craft intricate renditions of Jesus, Mary, and Biblical scenes in a distinctively Asian setting.

Wedding at Cana, Daniel Mitsui. (Source)

But all of this theorizing applies only to art which depicts sacred subjects. The art that Fr. Martin posted doesn’t do that. His interpretation is simply wrong. As some of the commenters noted, the very link he posted with the three images shows how off his view is. I will quote the source in full:

Yolanda Lopez has received the majority of her fame through the creation of her Guadalupe series. This groundbreaking series has transformed the way in which the iconic image of the Virgin of Guadalupe is viewed into a much more personal and political ideal. Lopez claims that in creating the Portrait of the Artist as the Virgin of Guadalupe she questioned this common icon of the ideal woman in the Chicano culture. The goal of Lopez was to demonstrate and consider the new types of role models Chicanas need and not simply adopt anything just because it is Mexican. Yolanda stated that by doing these portraits of her mother, grandmother, and herself she wanted to draw attention and pay homage to working class women, old women, middle-aged over weight women, young, and self assertive women. By naming each drawing individually Lopez emphasizes the uniqueness of each woman and accentuates the society that allows women of color to go unnoticed.

In the Portrait of the Artist as the Virgin of Guadalupe, Yolanda illustrates the strength and the power by the muscular legs and the long strides as well as the leap she has taking from the crescent moon. Through this long leap Lopez demonstrates that Chicanas are free from the oppressive social stigmas that limit women’s form of expression. In Margaret F. Stewart: Our Lady of Guadalupe, Lopez depicts her mother at work but proposes a new type of beauty. This new beauty is not the typical beauty that is depicted by others as the slender body type, white, young, and glamorous but as the older an fuller woman hard at work. Lastly in Guadalupe: Victoria F. Franco, Lopez illustrates her grandmother as a sad but strong old woman. In each portrait Lopez incorporates a serpent but the serpent in her grandmother’s portrait has been skinned and the grandmother holds the serpent skin in her left hand and the knife that was used in on her right hand. Lopez states “ She is holding the knife herself, because she’s no longer struggling with life and sexuality. She has her own power.” According to Dr. Davalos (author of Yolanda Lopez) the first two portraits represent lived realities of Chicana women and the last portrait address death.

(emphases in bold mine)

The Guadalupe paintings are not, as Fr. Martin insists, “beautiful images of Our Lady of Guadalupe, reimagined as contemporary women.” They are just portraits of the artist, her mother, and her grandmother incorporating the symbolism of Our Lady of Guadalupe. Lopez takes great pains to emphasize that, in her paintings, she is interrogating the received iconography of Guadalupe. The focus is on the poor Chicana as an icon in her own right, an icon that can surpass the role of Our Lady as a role model for contemporary women. This treatment of Guadalupe as an image of primarily moral and social significance is at odds with its presentation and reception by the Faithful. it is basically heretical. However, it’s hardly an uncommon practice today (though it must have been truly radical, if not exactly novel, in 1978). Our Lady of Guadalupe has become a symbolic nexus of all manner of discourses: Catholic, feminist, leftist, Immigrants’ Rights, Latinx, etc. But it doesn’t follow that every image of Guadalupe that engages those questions is properly understood as a “reimagining” of Our Lady.

Simply reading the source statement would have made all of this meaning clear. Fr. Martin must have either (a) not read the link he posted, (b) egregiously misunderstood it, or (c) willfully ignored it. In other words, his post was either lazy, imbecilic, or intellectually dishonest. Regardless, it was irresponsible. If he had bothered to look up some of Lopez’s other work, he might have avoided his grotesque mistake.

Portrait of the Artist as the Virgin of Guadalupe, Yolanda Lopez, 1978. (Source)

But even assuming that we take him at his word and accept that he genuinely thought these were perfectly sound “reimaginings” of the Blessed Virgin, what kind of sensibility does that judgment betray? How does Fr. James Martin think Our Lady can and should be “imagined?” It seems that the overt eroticism of Portrait of the Artist as the Virgin of Guadalupe didn’t faze him. Nor did “Mary” trampling on the angel. Nor did her highly unusual connection with the serpent. It is incredible that a priest, particularly one as culturally sophisticated as Fr. Martin, would miss these blasphemous irregularities in an image of the Mother of God. At the very least, his post fails to inspire much confidence in his sense of the sacred.

Fr. Martin’s talk of “imagination” is revealing. Imagination is one of the central components of Ignatian spirituality, as Fr. Martin himself tells us in The Jesuit Guide to (Almost) Everything (2012). He writes of Ignatian contemplation:

Using my imagination wasn’t so much making things up, as it was trusting that my imagination could help to lead me to the one who created it: God. That didn’t mean that everything I imagined during prayer was coming from God. But it did mean that from time to time God could use my imagination as one way of communicating with me. (The Jesuit Guide 146)

St. Ignatius of Loyola, Peter Paul Rubens. 17th century. (Source)

He then goes on to describe the practical method of Ignatian prayer.

There is much to recommend this spirituality, not least of which is the glorious roll call of Jesuit saints echoing down the centuries. But a danger lies hidden in Ignatian prayer. Grounded as it is upon the working of the individual psyche, it lacks the objectivity of, say, a liturgically-grounded spirituality. Without proper adherence to the mind of the Church, those engaged in Ignatian prayer can recede into a fuzzy personal relativism. In Fr. Martin’s case, it seems to have predisposed him to an overemphasis on the rights of imagination in the production of religious art. Note his use of vision discourse: “The artist, as I see it, was trying to remind us that Mary (Our Lady) was a real woman. And that the artist sees her in those around her, especially in Mexican women” (emphasis mine). Note that he never bothers to investigate the objective meaning encoded in the art itself – its formal characteristics, its use of symbols, its colors and patterns, etc.

Worse, his words imply a quietly Gnostic dissolution of both the meaningful category of physicality as well as the concrete propositions of dogma. Where does that leave us? It doesn’t matter if the Virgin Mary was a Jewish woman of the first century, nor if she was the Immaculately Conceived Mother of God. The imagination and spiritual vision of the artist is primary. Fr. Martin’s point, implicit at first and only later drawn out in reaction to his critics, is that Catholics should be affirming of those “reimaginings.”

But this is an untenable position in the face of actual art. The imagination is inevitably bound up in any artistic process, and it has often produced strange and wonderful innovations on older traditions (see, inter alia, the work of Giovanni Gasparro). But that fact does not isolate the pieces from serious criticism. We must judge; artistic discrimination is the very soul of good taste. And we must be even more critical for art that treats of the spiritual life, even at the cursory level of motifs. It aspires higher. As such, more is at stake. Fr. Martin’s banal pablum is a betrayal of the art he presents. It demands to be taken more seriously.

Pingback: FRIDAY CATHOLICA EXTRA – Big Pulpit

What specific criticisms do you have regarding these pieces? What exactly is wrong with them?

LikeLike

He was pretty clear: these are not religious images, but a kitschy mockery of religious images, and because that requires very little talent and practically no imagination, it is simply not real art. At best it might be a kind of political cartoon.

LikeLike

Fr.Martin does a lot of double talk and obfuscation of the clearly. Anti-crist and Our Lady and pro sexual, anti-moral symbolism.Talh is cheap,open your eyes and you see clearly ,this obscenity,topped off by alleged artists narcissism.She tries to create the Mother of God in HER own image!As for fr.Martin I think some time at in a Cistercian monastery would relieve him of his sudden and sacrilegious interest in profane art.Pray for them,they need it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Mr. Yoder,

You have done a masterful job taking apart Fr. Martin’s arguments defending these atrocities that clearly blaspheme the miraculous image of Our Lady of Guadalupe. How dare this artist appropriate a miraculous image of Our Lady for her own prideful purpose! And then to have one of our own priests see this work as something to praise? God save us from shepherds like these. I agree with D. Donovan. Our priests need a lot of our prayers.

LikeLike

Pingback: The Year’s Top Posts: 2017 | The Amish Catholic