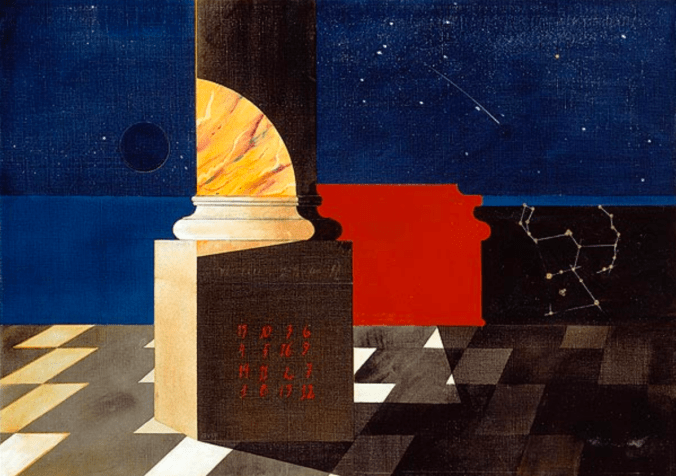

Wulf Barch’s prize-winning piece, The Labrynth, or the Book of Walking Forth by Day. 2011. (Source)

One of my recent discoveries has been the Mormon art world, formerly a dark continent for me. With the passing of the late Mormon president, I thought I might offer a window into an aesthetic realm that, I suspect, is still largely unknown to many. Most non-LDS people will have heard of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir. Some may be aware of the imaginative Book of Mormon illustrations by Arnold Friberg. And anyone who’s been on the internet long enough will recognize the utterly bonkers right-wing propaganda produced by Jon McNaughton. However, few know the very impressive offerings by contemporary Mormon artists.

Abinadi before King Noah (Abinadi Appearing before King Noah). Arnold Friberg. Note the curious mixture of Biblical motifs and Central American aesthetics. We have here a typically Mormon image. (Source)

Apparently, BYU has an excellent Fine Arts department. The jewel in their crown is Wulf Barsch, a Bavarian émigré who studied under the Bauhaus Masters, themselves trained by Klee and Kandinsky. After some flirtations with the Viennese school of Fantastic Realism, best represented by Ernst Fuchs, Barsch, we read, “studied Egyptian and Islamic culture and history.” These influences would come to the fore in his later work. He was baptized a Mormon in 1966, went to BYU to study Fine Art, and stayed there for some forty years.

Barsch’s work is marked by a few cardinal motifs. He always uses vivid colors, often structured by two juxtaposed elements: a blurred realism and a lightly sketched geometric design. This combination gives his work the slightly dizzy air of a dream – or, better yet, of a mystic vision, of some terrible sacral truth unveiling itself. The viewer becomes the prophet.

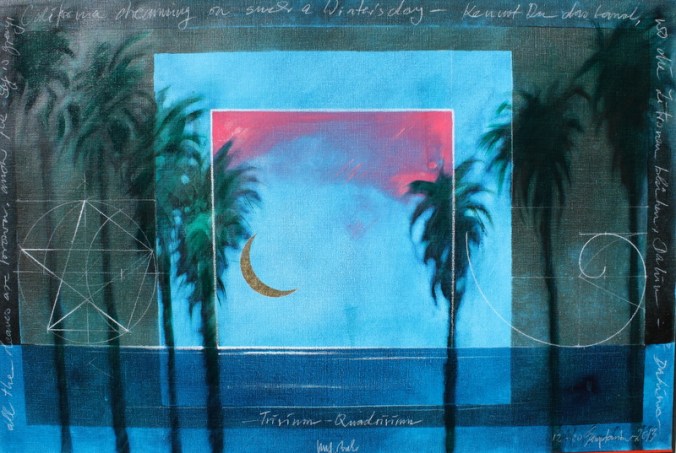

The Real Voyage of Discovery, Wulf Barsch. (Source)

Barsch’s study of Islamic art and its long tradition of sacred geometry has borne much fruit throughout his career.

The Measure of All Things, Wulf Barsch. 2009. (Source)

Barsch’s prophetic accents are heightened and canalized by a keen ritual sensibility. On those occasions when he does depict architectural details, they usually reflect the norms of temples: Classical, Masonic, and Mormon.

Jupiter Square, Wulf Barsch. Note the use of a Magic Square. (Source)

Et in Arcadia Ego, Wulf Barsch. 2010. The tiled floor, the pair of broken columns, and the orientalist flavor of the pyramids and palms all suggest a Masonic aesthetic. (Source)

He will sometimes write on the painting, adding a secondary symbolic layer to the image.

Title Unknown, Wulf Barsch. No doubt this will be of particular interest to fans of a e s t h e t i c s (Source)

Title Unknown, Wulf Barsch. (Source).

Observe, if you will, the piece above. Looking at this painting, we are struck by the contrast between the garlanded, barely visible columns and the stark yellow and red scene beyond. The most immediate impression comes from the color, which forms, as it were, the raw material of the art-world we see. Yet we can also glimpse geometric drawings in the yellow field and the outline of the columns. That which is artificial melts away before the manifestation of the absolute. Lesser being fades, even as it is heightened beyond its limitations under the demands of human artifice. Yet even in contemplating the absolute, we recognize something like our own reason. There is an intelligence there, an ideal that is only dimly mirrored in this dark world below. In short, Barsch has presented a model of mystical experience.

Or take another painting. Below, we see is, at first glance, little more than a tropical landscape. We can feel the heat through the stereoscopically blurred palm fronds. Yet upon further consideration, we find a celestial scene in the blue window – an impossibly delicate set of constellations in a field of bright bleu celeste. There is at once a sense of familiarity and otherness. Are we inside or out? We experience a de-familiarization of the scene. This sensation comes, appropriately enough, through the viewer’s discovery of heaven in the painting. Likewise, the soul feels a similar sudden reversal upon the discovery that there is a God. The subtle intrusion of the transcendent changes the way we look around us.

Title Unknown, Wulf Barsch. (Source)

Barsch is intensely interested in the way the numinous appears through creation. His vision is almost sacramental, with one important caveat. The presence of the transcendent that he describes is not resting in the material realm but in its ideal configuration. He represents this ideal world, as well as our access to it, by use of the Labyrinth, a frequent symbol.

The Labyrinth, Wulf Barsch. 2006. Note that it lies within the cliff, under the trees. (Source)

The same idea animates his Magic Square (2006). The titular magic square appears in the silhouetted palm tree, as if exposing its underlying mathematical nature. It’s as if Barsch is showing us God’s blueprints.

Magic Square, Wulf Barsch. 2006. (Source)

Barsch has won multiple awards, including the prestigious Rome Award, over his long and prolific career. He has also carried his talents across media. For example, here is one of his lithographs.

Title Unknown, Wulf Barsch. (Source)

Barsch continues to exert a major influence on the oeuvre of younger Mormon artists. Whitney Johnson, David Habben, and Nick Stephens all exhibit signs of Barsch’s lingering artistic vision.

A very different representative of contemporary Mormon artistic trends is Brian Kershisnik. An American who originally trained in ceramics at BYU, Kershisnik later moved to painting. He now produces spiritually sensitive figurative images that somehow capture the freshness and simplicity of the American West.

Descent from the Cross, Brian Kershisnik. Currently on display at BYU Museum of Art as part of their exhibit, “The Interpretation Thereof: Contemporary LDS Art and Scripture.” (Source)

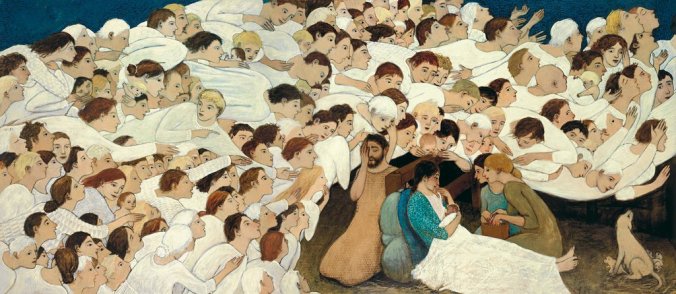

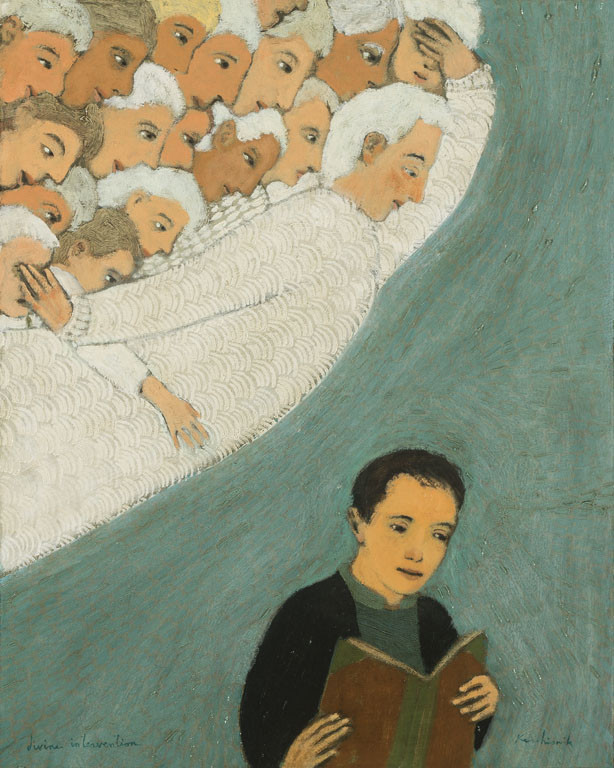

His religious art is very often in conversation with the canons of the Western tradition. Nevertheless, he infuses a certain ordinariness into scenes from the Bible. If Barsch presents a spiritual vision drawn from Mormonism’s Masonic and Orientalist past, then Kershisnik returns to its Low-Church Protestant roots. Even his crowds of angels look just like us.

Nativity, Brian Kershisnik. (Source)

Those angels, by the way, are profoundly interested in human life. Even fairly quotidien scenes betray an unseen presence.

Divine Inspiration, Brian Kershisnik. (Source)

Many of his characters are, quite literally, rough around the edges. In them, we can detect the faintest hint of Chagall. Particularly as so many of Kershisnik’s non-Biblical subjects seem to inhabit a stylized world hovering on the edge of allegory.

Dancing on a Very Small Island, Brian Kershisnik. (Source)

Kershisnik is fundamentally an artist of human dignity, and the quiet joy that springs from that dignity.

Holy Woman, Brian Kershisnik. (Source)

He also brings an understated sense of humor to much of his material, as in Jesus and the Angry Babies.

Jesus and the Angry Babies, Brian Kershisnik. (Source)

Note in A Quiet Shining Dance of Sisters how Kershisnik draws together line (the mirroring of the two profiles) and color (gold) and texture (the mosaic effect in the upper half of the image) to suggest a spiritual union that goes beyond the merely physical elements of the titular dance.

A Quiet Shining Dance of Sisters, Brian Kershisnik. (Source)

There are a few other Mormon artists worth knowing. Take, for instance, painter and illustrator Michal Luch Onyon, whose colorful and somewhat naive works are sure to delight. Or landscape artist Jeffrey R. Pugh, whose bold and strong brushstrokes evince the confidence of the West. He also created one of the more numinously beautiful depictions of Joseph Smith’s alleged vision, Early Spring, 1820. Finally, take a look at Nnadmi Okonkwo’s sculptures. The Nigerian’s graceful depictions of the human form are a testament to the respect afforded to women, and strike a beguiling balance between traditional African forms and American methods. His work is a testament not only to his considerable talent but to the great lengths which the Mormon church has traveled in its delayed acceptance of black members.

Title Unknown, Michal Luch Onyon. (Source)

Title Unknown, Michal Luch Onyon. (Source)

Mountain Aspen, Michal Luch Onyon. (Source)

A Day in the Life, Jeffrey R. Pugh. (Source)

Cumulus Creepers, Jeffrey R. Pugh. (Source)

Early Spring, 1820, Jeffrey R. Pugh. (Source)

Friends, Nnamdi Okonkwo. (Source)

Guardian, Nnamdi Okonkwo. (Source)

Title Unknown, Nnamdi Okonkwo. (Source)

The remarkable proliferation of Mormon fine art—not merely the kitschy stuff which characterizes so much religiously inflected work today—is certainly a sign of the faith’s expansion and self-confidence. Catholics should watch the continuing development of a specifically Mormon aesthetic as the LDS presence in society continues to grow.