Our Lady of Guadalupe, pray for us. (Source)

“Your deed of hope will never be forgotten by those who tell of the might of God. You are the highest honor of our race.”

Thus does the whole Church sing at Mass today, on the Feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe. And no mean words are they! The Psalm is drawn from the Book of Judith – a frequent verse for feasts of Our Lady – and it lands on our ears like a shout of proleptic joy in this season of preparation and penance. The liturgy draws two special comparisons between Mary and the women of the Old Testament: Mary as the new Eve, and Mary as the second Judith. Today’s feast draws its special energy, its exegetical verve, from the mystical connection between Mary and Judith.

Our Lady of Guadalupe painted by the Trinity. An image worth meditating on. (Source)

The particular verse that the Church applies to Mary comes from Uzziah’s praise of Judith after she has already beheaded Holofernes the Assyrian. Let us turn briefly to the immediately preceding passage.

Then she took the head out of the bag, showed it to them, and said: “Here is the head of Holofernes, the ranking general of the Assyrian forces, and here is the canopy under which he lay in his drunkenness. The Lord struck him down by the hand of a female! Yet I swear by the Lord, who has protected me in the way I have walked, that it was my face that seduced Holofernes to his ruin, and that he did not defile me with sin or shame.” All the people were greatly astonished. They bowed down and worshiped God, saying with one accord, “Blessed are you, our God, who today have humiliated the enemies of your people.” (Judith 13:15-17).

Then come our Psalm verses.

Judith Beheading Holofernes, Caravaggio, c. 1602. (Source)

Why would the Church draw our attention to this violent episode on a feast of Our Lady falling so soon after the Immaculate Conception? Haven’t we just contemplated her Sophianic existence? Haven’t we just basked in the light of the Holy Spirit resting upon her Immaculate Heart? Why must we leave those pleasant snow-caps of the spirit? Why turn instead to this grisly tale of murderous deliverance?

We must recall that, although Mary is all sweetness and concord to those who love her Son, she is the terror of demons. Her litanies and devotions include many titles that evoke the clamor of warfare: “Tower of David,” “Tower of Ivory,” even “Gate of Heaven.” She crushes the head of the Serpent. The sword that pierces her heart becomes, by the union of her suffering with that of her Son, a fearful weapon in her mighty hands.

“Hail Mary, full of grace, punch the devil in the face.” (Source)

The story of Guadalupe is just one example of Our Lady exercising this power. Her appearance on Tepeyac, and the miracle wrought on the tilma of St. Juan Diego, was the beginning of the end of Aztec paganism. The demons that held that great people in thrall to the murderous rites of human sacrifice were totally vanquished. Like Judith, Mary rode out from Heaven into the very camp of the enemy. Like Judith, she conquered. Like Judith, she proclaimed her victory with a visible sign – only, Our Lady’s sign was far more glorious. Judith held up the head of the vanquished foe, the bloody remains of a wicked oppressor. The Mother of God gave us her own image, miraculously imprinted into the convert’s cloak.

Judith delivered the Jews from the army of the Assyrians. Mary came forth to Tepeyac to convert the Mexican people, lifting from them the demonic yoke of a bloodthirsty paganism. What a glorious victory she won! Nine million Aztecs converted within the first ten years of the apparitions. Even today, she continues to spur us to conquer those terrible forces of injustice that oppress so many of God’s people. The collect prayer for today’s feast reads:

O God, Father of mercies, who placed your people under the singular protection of your Son’s most holy Mother, grant that all who invoke the Blessed Virgin of Guadalupe, may seek with ever more lively faith the progress of peoples in the ways of justice and of peace. (Source; emphasis mine)

These days it is rather in vogue to lament a certain kind of triumphalism that is built on self-centered pride. But too often we forget that there is another triumphalism, the shout of a people who have seen their salvation coming from the Lord:

Blessed are you, daughter, by the Most High God,

above all the women on earth;

and blessed be the LORD God,

the creator of heaven and earth

(Judith 13:18).

The Church herself enjoins us to celebrate the works and ways of God through His chosen instruments. And in today’s Mass, we are called to join that praise to the sacrifice of Christ in the Eucharist.

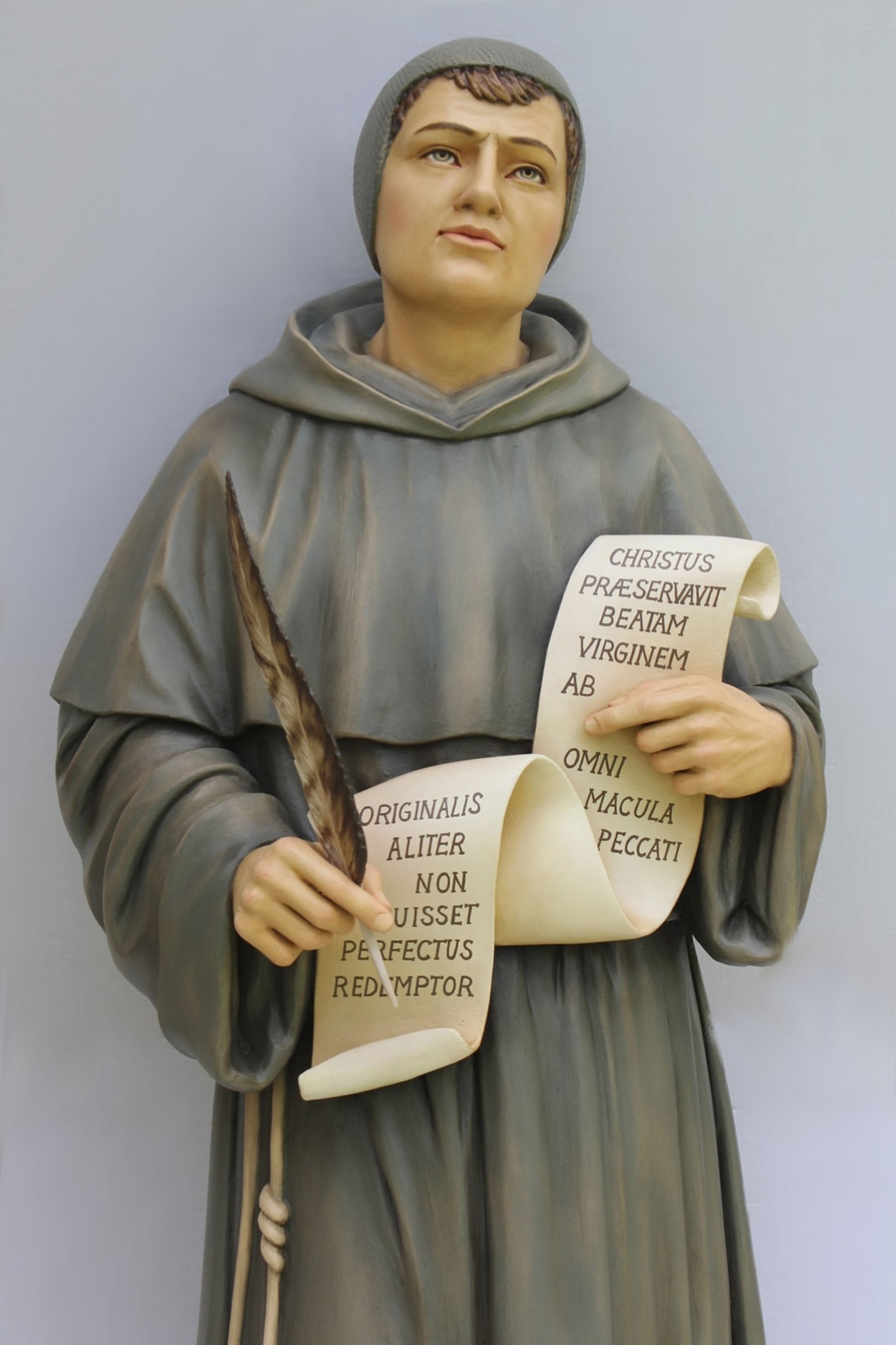

Our Lady of Guadalupe, Victrix over All Heresies and Demons. (Source)

In considering Our Lady of Guadalupe and the zeal with which she overcame the forces of evil and in contemplating the beauty of her miraculous portrait, a verse of Scripture comes to mind.

“Who is she that cometh forth as the morning rising, fair as the moon, bright as the sun, terrible as an army set in array?” (Cant. 6:10 DRA)

We who have seen the tilma through the eyes of faith know the answer.

Our Lady of Guadalupe, Mystical Rose. (Source)