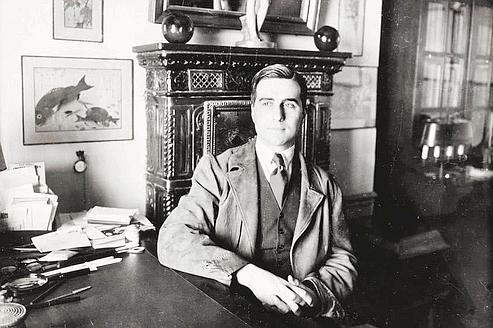

Julien Green (1900-1998), c. 1935. One-time student at the University of Virginia. Source.

As a student of the University of Virginia, I have been bombarded with official propaganda about the history of the Great Men (and, much later, Women) who “wore the honors of Honor.” Poe in particular is a favorite example, and certain elements of UVA culture such as the Jefferson and Raven Societies are suffused with the memory of his presence. We even commemorate him by setting apart a room on the West Range which we claim, without proper evidence, to be his. No matter. The great poet did live in the Academical Village before he dropped out, and he’s too important a figure not to use in a marketing ploy. The presence of William Faulkner is more understated, though an outstanding exhibition currently on offer at the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library is correcting that imbalance. So, too, members of the Jefferson Literary and Debating Society recall fondly that he accepted honorary membership of their esteemed organization, once delivering an address with John Dos Passos in attendance.

I might also add, for those who enjoy fine beverages, that Faulkner’s grandson owns and runs a superlative small winery on the outskirts of town. The resemblance is uncanny.

But one author who left his footprints on Mr. Jefferson’s Grounds has gone sadly unnoticed by the vast majority of students. That man is Julien Green. I imagine that, if I were to ask any passing student about Julien Green, they would have no idea who he was. Yet in his own day, he was a major player in the French literary scene, interacting with such characters as André Gide, Jacques Maritain, Lucien Daudet, Gertrude Stein, Georges Bernanos, and many more. He even reached the pinnacle of literary achievement in France, eventually becoming the first American ever elected to the Académie française.

This oversight becomes more egregious in that, unlike Poe and Faulkner, Green wrote prolifically about his time at UVA. Indeed, he even set one of his novels at the University—including a scene in front of a specific Lawn Room, 34 East. In the same book, he gives one of the most beautiful descriptions of the old Rotunda library that I have read; it still makes me proud to be a student at UVA, although the building has changed radically since that age. I am sure that in the years to come, I will return to that passage with no small dose of nostalgia.

Green’s Van Vechten portrait, Nov. 11, 1933. Source.

The scion of two old Southern families—one from Georgia, one from Virginia—Green was born in Paris in 1900. He spent his youth hearing stories of the old Confederacy, which his mother romanticized incessantly. After World War I broke out, he served in both the American Red Cross and the French Army. When the fighting finished, he shipped off to college in the United States, a land he had never before seen.

Green was a student at the University from 1919-1921. By all accounts, he did not enjoy his time in Charlottesville. He was a remarkably proficient student, able to complete all of his academic duties by ten before spending the rest of the day with his books in the Rotunda. He was particularly fond of The Critique of Pure Reason. As a teenage convert to Catholicism, Green also felt alienated from his WASP peers. The University had no Catholic chaplaincy, so he had to trudge all the way down into the city to the rickety wooden mission parish (now Holy Comforter).

As the only Catholic parish in Charlottesville at the time, the “Church of the Paraclete,” later Holy Comforter Parish, must have been where Green received the sacraments. But he describes it as a wooden church, not the brick structure that we know it to have been. This is a puzzle which more research could, perhaps, solve. (Source).

Anti-Catholicism wasn’t the only religious prejudice that infected the University’s culture. Green muddled through an independent study of Hebrew with a noticeably unpopular, albeit good-humored, Jewish student whom he calls “Drabkin.” Antisemitism must have been an entrenched, unquestioned part of student life then. Green was not an antisemite, and he would later return to the language after many years. In his later life, he relished the texts of the Old Testament (Diary 1928-1957 65-66).

The Lawn. Date Unknown. Source.

Virginia students will recognize certain eternal experiences that Green records in the third volume of his Autobiography, entitled Love in America (the cover shows the Rotunda from University Avenue). He likely lived in the block where Boylan, Fig, and Mellow Mushroom stand now, though possibly as far as Wertland. He describes a scene in his boarding house, which gave him a view “over the main avenue which led to the University, as well as the bridge across which the express train would rumble four or five times a day” (Love in America 71). Later, he moved to a house at the end of Chancellor Street, owned by an old woman named Ms. Mildred Stewart (Love in America 172-73).

The view of the bridge looking towards the University, c. 1906. This approximates the view that Green describes from his first accommodations. (Source).

While in Charlottesville, he admired the University’s physical beauty, writing,

Life at University was slow to start again, for no one was ever in a hurry there, but by the end of the first week classes were full once more, and students yawned in the pleasant September weather. At Cabell Hall, the scent of honeysuckle hung over each window casement, and in the hall the plastercast of Hermes in all his majestic immodesty rose above the heads of the boys who walked past the level of his knees. (Love in America 131).

Evidently Old Cabell, before it was “Old,” had a few classical (nude) statues positioned around the staircases. One can only imagine what Green would think of the beautiful but controversial mural that now adorns its walls. He did go to attend convocation and other functions in its concert hall, where even then a large reproduction of “The School of Athens” graced the stage (Love in America 133).

The University’s first copy of “The School of Athens,” then in the Rotunda Annex (prior to 1895, when the Annex burned down). By Green’s day, a replacement had been placed in Cabell Hall. Interestingly enough, the chairs in the photo resemble those in Hotel C, and the motto hanging at the top—Haec Olim Meminisse Iuvabit—matches that of the Jefferson Literary and Debating Society. (Source).

The Old Cabell mural by Lincoln Perry. Source.

And of course, he writes about the Rotunda. In 1937, Green was back in Charlottesville. In his Diary, we read that he would often ponder whether Poe studied at the same tables in the same “old library,” i.e. the Rotunda (72). As I mentioned earlier, Green would go on to compose one of the best literary depictions of the Rotunda in his 1950 novel, Moira:

A few minutes later he was mounting the library steps and pushing open the heavy door…The warmth of the large, round room was pleasant and he stood there for a few seconds, his face relaxing. Finally he took off his overcoat and looked for a table, but the best places were taken. Everywhere there were students reading, or snoozing, overcome by the warmth under the great dome. In the silence he heard the hissing of the radiators. Joseph walked almost right round the library on tiptoe before he found a place behind a great pile of overcoats and scarves on a table. With a sigh of weariness he sank into an armchair…How comfortable it was! A delicious warmth flowed into his hands, his legs, all through his body. With his elbows on his legs, he linked his fingers over his stomach and looked curiously out of the window. Everything was hidden in snow. The tips of the magnolia leaves near the library could just be seen like black tongues. The little brick path had been cleared. Joseph had often heard it said that nothing ever changed at the University, but this morning, for the first time, he felt a sort of gratitude for everything that did not alter. Generations of young men had sat there in that corner and, like him, looked out over the little brick path. In the spring and autumn the wistaria hung all over the arch on the right. This morning the snow allowed only a few black and twisted branches to be seen, but there would be wistaria again. The snow would melt, but under the snow were all those dead leaves…(Moira 221-22).

Green certainly based the scene on his own recollections. The Rotunda was one of the very few places where he could be happy, alone among the quiet genius of dead men. In his Autobiography, he calls it a “pink Pantheon” and tells us,

If I looked to the left, I could see the curves of Houdon’s bronze bust of Washington. To the right were the clumps of laurel trees, still green after the first snows. Like those who frequent certain cafes, I had my particular place, my preferred alcove. What dreams did I not drift into there? (Love in America 57-58).

Morning in the Academical Village. The magnolias that Green describes were taken down in the recent renovations. Photo by the author, Mar. 16, 2017.

Cover of a Spanish edition of Moira (1950), implicitly set at the University of Virginia. Source.

He spent time on the Lawn, a place that would hold tremendous personal meaning for him, as we shall see. Green writes of the Lawnies and their rooms,

These privileged individuals did not live just anywhere. On either side of the long lawn, built into the brick walls, there were the dark green doors [they are red today] that I mentioned before, each with its brass number and frame that held a visiting card. Once one had gained access through one of these doors, you found yourself in a sort of cell. Daylight came in through a sash window and in cold weather the room was heated by lumps of coal which smoked in the fireplace, exactly as in English Universities…The obligatory rocking-chair could be seen in one corner, but when the weather was fine, one dragged it outside on the Lawn and studied beneath the trees [I and many others have continued this tradition]. These two galleries which faced each other were known as East Range and West Range [I have no explanation for why Green would write this, except that perhaps all the rooms in the Academical Village were once called by the title now only given to those that face away from the Lawn]. I never think of them without sadness after so many years. I little knew how much pain awaited me there. (Love in America 55).

There are other similarities between his time and ours. Green knew the irritation of construction, as he was there for the start of work on the Amphitheater (Love in America 194). He went to something very much like Foxfield: “One day, I was taken to the races at Warrenton in the north of Virginia. Everyone in the South knew Warrenton. Once a year, the races took place there and people came from all around” (Love in America 125). He published a story in one of the University magazines, Virginia Quarterly (Love in America 168). He even read The Yellow Journal, which he describes in the following terms:

…little more than a scandal sheet, designed to make people laugh. All sorts of personal insinuations were made, but in such a way that those who complained only did harm to themselves. The editors were diabolically cunning [still absolutely true]. People tolerated The Yellow Journal with good humor that occasionally turned to anger, for people were terrified of appearing in it. (Love in America 191).

Cabell Hall Peristyle, c. 1920. Green would have passed by these columns every day. Today, the hulking mass of Bryan Hall looms behind them, and no ivy grows there. (Source).

He took History classes in the Rotunda under a Professor Dabney, very probably the Richard Heath Dabney who gave his name to one of the Old Dorms (Love in America 170). In one of the more humorous points of the Autobiography, Green tells us that the fervently Protestant Dabney, having heard that there was a devout Catholic student in his lecture, went out of his way to emphasize the depredations of Romanism. Many years later, when Dabney learned that Green had become a novelist and not a priest, he is reported to have said, “Anyway, it’s due to me that he remained a layman” (Love in America 170-71). There is also an extremely amusing episode in his Autobiography in which Green is hit up for donations to President Alderman’s funding drive.

One evening, as I was studying in my room by the light of the oil lamp…the door was pushed open and I saw two large boys whose build suggested they played football…

“Good evening,” said one of them. “Are you Green, Julian Green?”

“Yes, I am.”

“Do you love this University?”

“Well…”

“Of course he loves it,” said the other. “It’s his Alma Mater. So you’re going to give a nice present to your Alma Mater, a present of one dollar, and then you will sign there,” he added, placing a printed card before me.

I read it without knowing what it said. “I don’t understand,” I said.

“That doesn’t matter. Just give a dollar like a gentleman.”

I gave them a dollar.

“Good. The rest is merely a formality. You commit yourself to paying two dollars every year.”

“For how long?”

“Until the Lord calls you to him…There, do you see this dotted line? That’s where you sign, like a true Virginian gentleman. Otherwise…”

“Otherwise what?”

“Otherwise the University will realize it has been mistaken about you.”

I signed.

“Good evening,” they said as they left. “It’s been a pleasure chatting to you.”

(Love in America 159-60).

Did someone mention the Class Giving Campaign? (I kid..I kid…)

Green was known for his books that combined penetrating psychological portraits with Catholic spirituality and an exploration of sexual guilt. He also made a major impact on French letters through his multi-volume Diary, which stands as one of the most important pillars of 20th century French literature. It is an invaluable source for scholars of several major writers. Source.

The Amphitheater, c. 1920. Green was there when construction began. (Source).

Yet at the end of the day, Green’s experience at the University cannot be described as all that similar to our own. He records things as they once were, and are no more. On the occasion of a return trip in 1933, he writes,

At the University. She is the same as ever, cordial with that shade of disdain that gives her so much charm. Her vast lawns bordered by Greek Revival columns reflect a peaceful soul, perfectly satisfied with herself. You call on her, a hand is extended with a smile. If you turn away from her, if the whole of America forsook her at the foot of her hills, she would none the less pursue her quiet dream, adorned with classical literature, white frontages, black foliage. From North to South, what could there be for her to envy? Isn’t she Mr. Jefferson’s daughter? (Diary: 1928-1957 47).

This romantic depiction of the University overlooks several of the very real problems, particularly racial ones (“white frontages, black foliage”), that plagued the University and the South at that time. And certainly, no one living in Charlottesville today could seriously write about UVA like this. It’s too large and worldly, and we all have a much clearer sense of collective sin than Green did. There is a certain literary irony in this blind spot, as Green was deeply indebted to that bard of guilt, Nathaniel Hawthorne.

But Green saw enough changes to realize that the University he remembered at the cusp of the 1920’s no longer existed. When he returned in 1937, he was deeply displeased with President Newcomb’s expansions.

Visited the new buildings, none of which are fine. The old University is intact, but while it used to be surrounded by woods, meadows, and ponds, as in Mr. Jefferson’s time, it now suffocates within a belt of big, commonplace houses. Useless to tell me that the buildings were very expensive, that doesn’t give them any more merit in my eyes. No, what happens to cities and universities is what happens to men: wealth kills something in them that can never again be found or replaced. Now that the University has become one of the big American universities, with a gymnasium the size of a railroad station [Mem Gym], a dormitory as big as a barracks [Old Dorms], etc., it attracts an increasing number of Northern boys, and I find no fault in this, but note that it is hardly any longer a Southern university. Its professors come from all over the country…(Diary: 1928-1957 72-73).

We who have passed our time here in the 21st century, almost a hundred years after Green left, must stifle a chuckle at his somewhat provincial complaint. It’s not hard to imagine what he would make of the Engineering School, Ruffner, New Dorms, Runk, Scott Stadium, Nau-Gibson, or New Cabell…let alone the sprawling monstrosity that is the medical complex. And you will be happy to know that Green could honestly describe Fourteenth Street in the Year of Our Lord 1921 as “rather gloomy” (Love in America 172).

Julien Green, c. 1957. Source.

But in addition to religious pressures and the ordinary stresses of student life, Green’s time at the University was deeply unhappy for another reason. It was there that he discovered something about himself that would mark his writing for the rest of life. While studying Latin with Dr. Fitzhugh (almost certainly the namesake of the crummy dorm on Alderman Road), Green had an epiphany.

The day eventually came when Dr. Fitzhugh…coming to a passage of Virgil, made the following speech to us, not a syllable of which have I forgotten:

“Gentlemen, it seems pointless for me to disguise the meaning of this passage: we are dealing here with the shame of Antiquity, by which I mean boy-love.”

These words fell on an extraordinary silence, so much so that when I closed my eyes I believed I was alone in the room…The rapt attention with which everyone listened should have apprised me, had I been capable of reasoning, but I felt so dumbfounded it was as if someone had struck me a violent blow to the head. In a second, I understood a thousand things, except for one which was essential. I realized that the strange passion of which Virgil spoke resided also in me. A blinding flash had clarified my entire life. I was frightened by this revelation which identified me with the young men of Antiquity. So I bore the shame of Antiquity, I alone bore it. Between me and these generations that had disappeared over twenty centuries ago there was this extraordinary link. In the modern world, I was alone because of it. (Love in America 49-50).

Green realized that he was a homosexual. As fellow student Mr. Thaddeus Braxton Woody (“Mr. Woody, may he always be remembered”) would later note, Green was never a very happy student. His shame compounded his sense of isolation. And it would not be long before he fell in love for the first time. That winter, when walking back from Cabell Hall towards the Rotunda, Green spotted a boy who darted past him swiftly, without even a word. It was a coup de foudre. He was totally captivated. Green tells us that, after a spell of motionless awe in what was probably the East Lawn colonnade, he went back to his room and thought, “I love him…I shall have to die” (Love in America 79). Green was “enslaved” to a love that dare not speak its name (Love in America 79). When Green would later write the story of his life, he called the mysterious student “Mark S.,” but revealed that he lived in 34 East Lawn (Love in America 90). Two students lived in that room in the Spring of 1920, so if your curiosity gets the best of you, you are welcome to search the Lawn Resident database to discover their names. It is impossible to know which of the two won Green’s unrequited love.

And it was an entirely un-erotic love at that. Green was spiritually attracted to Mark. He could easily distinguish between the innocent tenderness he felt for Mark and the darker, carnal desires that characterized his thoughts about some of the other students—including Virginius Dabney, son of that zealously Protestant lecturer and later an important scholar and journalist in his own right (Love in America 91, 171-72). Only towards the end of his time at the University did Green ever pluck up the courage to speak to Mark, who welcomed him as a dear friend. He never did grasp the depth of Julien’s affections (Love in America 255-59).

Old Cabell Lobby, c. 1914. The statues in Cabell were a source of some temptation for Green, and helped him understand his homosexuality in a specifically classical context. They also appear in Moira (1950), where the Puritanical protagonist finds them repulsive. (Source).

Green never consummated his desires in Charlottesville, but by the time he left, his sexual awakening was more or less complete. He was aided in arriving at this “transformation” of awareness by a similarly-inclined student whom he calls “Nick” in his autobiography. Nick shared stories of his own encounters, introduced Green to the work of Havelock Ellis, and encouraged him to a sexual adventurism that Green was never to take up (inter alia, Love in America 202-04, 209-11, 214, 266).

Any reader of Green’s novels or diaries knows that homosexuality would go on to become one of his constant themes, even when it exists beside more conventional relationships. The memory of that first, innocent love with “Mark” would later fuel the novel he wrote about the University, Moira (1950). Mark appears in the story as “Bruce Praileau,” a handsome Lawnie who shares an unspoken sexual tension with the main character (Moira 15). In fact, most of the male characters in that book correspond to one or two of the figures in the Autobiography, including a Mephistophelean young professor of Classics who introduced Green to the sodomitical poetry of Petronius and Catullus at an evening party (Love in America 240-42). Even beyond Moira, Green’s fiction very often explores issues related to the homosexual experience in the middle of the 20th century.

Julien Green at about the age he would have attended the University. Source.

The energy and complexity of that exploration lies not only in his own relationships, but in his intense spiritual vision. Even in Moira (1950), the main internal conflict takes place between the protagonist’s repressed sexual urges (both for women as well as, implicitly, men) and his zealous, Puritanical religion. His competing fanaticisms eventually erupt into an act of violent destruction, but I won’t spoil the plot for those of you who may wish to read it.

Green’s time at the University transpired at the latter end of his first conversion. He had been received into the Catholic Church as a teenager, during the War. He would later leave the Church after his return to Paris, and spent the better part of two decades in the bohemian lifestyle which so strongly characterized the French literati of that age.

Yet even in this period, he retained a constant belief in God and a devotion to the Bible. In the late 1930’s, he returned to his Catholic faith. He would persist in it, albeit at times imperfectly, for the rest of his life. He broke off sexual relations with men, including his long-time partner and biographer, Robert de Saint Jean (though their emotional and spiritual relationship continued). He hated to be called a Catholic writer, but Green did acknowledge that his works “allow glimpses of great dark stirrings…the deepest part of the soul…the secret regions where God is at work” (Diary: 1928-1957 190). Green went so far as to write a life of St. Francis of Assisi, a saint to whom he always felt a certain inexplicable attraction. One reporter notes that “When asked, tactlessly, how he would like to die, he replied with a curious malicious twinkle in his eyes: ‘In a state of grace.'”

So, why would I title this largely historical post “UVA’s Own Saint?” Because I shamelessly want page views, of course. But also because I believe that Green’s work exhibits a spiritual mastery which is rarely acknowledged. He has been overlooked, I think, in large part because of his homosexuality. Occasionally, even conservative Catholic activists will tip their hats to Green (see Deal Hudson’s “The 100 Best Catholic Novels I Know,” where no fewer than three of Green’s books make the list—or the 1996 Crisis Magazine article on Love in America, written in a tone that differs rather markedly from the journal’s more recent fare. Hudson has long admired Green, and even corresponded with him in the mid-90’s). On the other hand, Spiritual Friendship, a blog that has done so much to change the conversation about homosexuality in the Church while remaining faithful to Catholic orthodoxy, has never really given much thought to Green.

But it would be a colossal mistake to treat Green as a “gay” Catholic writer, as if his work can only speak to the narrow concerns of a minority within the Church. He must not be made a football subject to the ephemeral concerns of the culture warriors. Catholics should pay more attention to him because his spiritual insights speak to the depths of the human condition. What is unique in Green is the way he draws those universal ideas from his own very particular situation. Like St. Augustine in Antiquity, Green perfects the art of discerning the divine meaning of memory. Much of his spiritual vision is concentrated in his personal, autobiographical, and reflective writing. For example:

St. Augustine of Hippo. A major influence on Green. (Source)

The Eternal is the most beautiful name that has been given to God. You can think it over until you lose all feeling of the exterior world, and I think that, in a certain manner, it is in in itself a way that leads to God. If we seek what is eternal in the sensuous world, all the manifestations of matter vanish from our sight, what is most solid together with what is most ancient, until we reach the limits of what is imaginable in all possible spheres. When I was still a child, I used to think over occasionally the term for ever and ever that Protestants add at the end of the Pater, and the words finally gave me a sort of mental dizziness, as though by continuing in that direction you would reach something inexpressible, an immense void into which you fell. (Diary: 1928-1957 76).

In this passage, he echoes sentiments that Newman felt and expressed nearly a hundred years earlier in the Apologia, and anticipates several of the key themes that would mark T.S. Eliot’s spiritual poetry. But perhaps more importantly, these words reveal Green’s basically Augustinian orientation, the legacy of both his Calvinist upbringing and his Catholic reading.

That deep longing for happiness, that longing I have in me, as we all have, so much so, for instance, that I can’t listen without melancholy to a bird singing on a too fine summer day in Paris, where does it come from? It is not merely the longing to possess everything, formerly so strong in me; it is a painful and sometimes pleasant nostalgic longing for a happiness too far away in time for our brief memory to retrace it, something like a recollection of the Garden of Eden, but a memory adapted to our weakness. Too much joy would kill us. (Diary: 1928-1957 81)

All the dead are our elders. When a child of ten dies, he is my elder because he knows. (Diary: 1928-1957 124).

François Fénelon, another significant influence. (Source)

As might be expected, he had a particular concern for questions of the human body and the importance of chastity. In his Diary, he often ponders the body’s potential and limits in the spiritual life:

Vice begins where beauty ends. If one analyzed the impression produced by a beautiful body, something approaching religious emotion would be found in it. The work of the Creator is so beautiful that the wish to turn it into an instrument of pleasure comes only after a confused feeling of adoration and wonder. (Diary: 1928-1957 93).

Chastity is the body’s nightmare. The soul is certain of its vocation, but the body’s vocation is physical love. That is its mode of expression, the way it fulfills its part; that is all it thinks, that is all it thinks about. How can you expect it to understand the soul’s care? That body and soul are forcibly wedded is a mystery. The body hates the soul and wants it to die…To remain chaste does not necessarily make a saint of you, but chastity is one of the hallmarks of holiness, and if you wish to be chaste, you also wish to be holy, without daring to admit it, perhaps. (Diary: 1928-1957 203).

Sin occupies a major portion of his attention:

Blaise Pascal, a major influence. (Source)

One loses all in losing grace. Many a time have I heard this said, but it is curious to observe that a single sin disenchants the whole of the spiritual world and restores all its power to the carnal world. The atrocious chaos immediately reorganizes itself…A veil stretches over the page. The book is the same, the reader’s soul has grown dark…a single act of contrition is enough for this wretched phantasmagoria to vanish and for the marvelous presence of the invisible to return. A man who has not felt such things does not know one of the greatest happinesses to be had on earth. (Diary: 1928-1957 300).

He had an exceptionally strong sense of the ineffable mystery at the heart of Christianity, drawn in large part from his reading of Scripture:

Faith means walking on waters. Peter himself had begun to sink when Jesus stretched out His hand, reproaching him for doubting. Now, we must believe. In an atheistic world, we have received this exceptional gift. In wind and in darkness, if the ground gives way under our feet like water—and who has not felt this at some time or other?—we must go straight ahead, in spite of all, and grasp the hand that is stretched out to us. (Diary: 1928-1957 273).

It is useless to attempt to get ahead of divine action. Our soul is an abyss into which we vainly peer. We scarcely see anything, but something is happening there—a great drama, surely; the drama of Adam’s salvation. The Church puts these things to us as best it can, but in a necessarily imperfect tongue, that is, the human tongue. It makes us familiar with extraordinary ideas that lose much of their strength with time. Happy the man who, in growing older, can feel the mystery increasing beyond all expression…(Diary: 1928-1957 284).

The two great Carmelite doctors, St. Teresa of Avila and St. John of the Cross. (Source)

How I loved the word firmament when I was still a child! To me, it seemed filled with light. My first purely religious emotion, so far as I can remember, goes back to my fifth or sixth year…The room was dark, but through a window-pane I saw thousands of stars shining in the sky. This was the first time, to my knowledge, that God spoke directly to me, in that vast, confused tongue which words have never been able to render. (Diary: 1928-1957 296).

Yet, in spite of himself, he could also sum up the most profound mysteries in brief and simple words:

What then did this book [Faith of Our Fathers, by Cardinal Gibbons] tell me? It revealed to me that even if I were alone in the world, Christ would come to save me. And it was the same for each of us. Why? For what reason? For love. God is love. When one has said that, one has said everything. (Letter to Deal Hudson, 1995)

The contours of his spirituality were shaped by a number of writers. Among many others, we find the lingering presence of St. Augustine, Pascal, Fénelon, Newman, Bossuet, St. Francis of Assisi, the Carmelite doctors, the Jesuits, Jacques Maritain, Bloy, Claudel, Bernanos, and one rather important nun who is often overlooked: Mère Yvonne-Aimée de Jésus, of the Augustinian Monastery of Malestroit in Brittany. Dom Mark Daniel Kirby has an excellent post over at Vultus Christi outlining the connection between the nun and the writer.

Mère Yvonne-Aimée de Jésus. (Source)

Green maintained relationships with many communities over the course of his life. For instance, on October 25, 1947, he visited the famous Solesmes Abbey. He was impressed with the solemn chant and hymnody he heard there. Green had only the highest praise for the monastic vocation:

The monks in their black robes seem to glide over the surface of the floor like ghosts. On their faces, pax, as everywhere in this place. Peace and joy…It seems to me that Benedictine life is one hymn of happiness and love, in a rather slow mode, true enough, but what charm in this slowness and how precious it seems to me in a world that a passion for speed has made almost idiotic! A hymn, that’s what it is…It occurs to me at times that these monks live in a sort of great liturgical dream, whereas, in reality, they are the ones who see things as they are, and we are the ones who live in a dream always on the verge of turning into a nightmare. (Diary: 1928-1957 190).

No doubt, he wrote these words with a degree of wistful melancholy. In Green’s first flush of religious zeal, he had been received into the Church by one Father Crété, a Jesuit who also encouraged him to pursue a vocation as a Benedictine at Quarr Abbey, on the Isle of Wight (Kirby). That was the life he left behind when he came to America, stepped into Fitzhugh’s Latin class one day, and discovered that he bore “the Shame of Antiquity.”

Green in his later years. He died just before his 98th birthday, only a few days prior to the Feast of the Assumption. (Source)

Julien Green would be worth remembering here at UVA if only because of his accomplishments as a writer. In the words of his obituary,

Green’s earlier novels – Mont-Cinere (1926), Adrienne Mesurat (1927), Leviathan (1929), L’Autre Sommeil (1931), Epaves (1932), Le Visionnaire (1934), Minuit (1936), Varouna (1940) – with their brooding melancholy and troubling sexual undertones, are masterpieces of psychological subtlety and crystal-clear but evocatively poetic style…But undoubtedly Green will chiefly be remembered for his extraordinary journals, the longest in French literature; those so far published cover 70 years (1926-96) while Gide’s cover 62 (1889-1951). There are more to follow…His prizes and honours are innumerable. (Kirkup).

But he offers so much more than a literary legacy. Julien Green’s star is fixed in the celestial canon of the greatest Christian artists the modern world has seen. He deserves a place alongside those other artists who share his temperament and spirituality: Flannery O’Connor, Graham Greene, Shusaku Endo, Paul Verlaine, Joris-Karl Huysmans, Georges Rouault, T.S. Eliot, and Fyodor Dostoevsky. His life story sits uneasily in the restrictive and politicized categories we draw to understand the sometimes dizzying diversity within the communion of saints. He and his work challenge us. Catholics—particularly Catholics at the University of Virginia—should embrace that challenge.

But perhaps the most basic plea I can make is that Julien Green is one of us. He was a student at the University of Virginia. His experience in Charlottesville profoundly marked his soul and his art. It may not have been a happy time in his life, but it changed him forever and left him with a profound gratitude for Mr. Jefferson’s University. How many of us can say the same?

Green’s diary reveals that, years after he left UVA, he came to appreciate it in a much deeper way. On December 6, 1933, in anticipation of a return trip, he writes,

It has been eleven years since I left [the University], and I wonder if I will be sad or happy to see it once more. No doubt I did not know how to benefit from all it offered me; I did not quite understand the University, and it did not condescend to explain itself. It was only once I left that I realized how deeply I loved it and was unknowingly immensely indebted to it. But in 1920 I missed France too much. At twenty, in one of the most beautiful landscapes in the world, without a worry for the future, I contrived every day to think myself unhappy. Ah! if everything had to be lived over again, with the experience that I have acquired since! How many friendships were offered me and discouraged by my lack of sociability! (Diary 1928-1957 45).

For an undergraduate about to walk the Lawn at graduation, I can’t help but relate to Green’s introspection. The words he wrote on what was, I believe, his last visit, June 12, 1941, are particularly poignant. He composed that entry while in exile during World War II, but the questions he poses loom before all of us who are soon to move on. I would like to offer them for your consideration.

At the University, toward the close of the same day. All the students have gone; everything is given up to solitude and to memory. We strolled on the big lawn that spreads before the Rotunda: great trees whispered above our heads, rows of white columns glimmered in the twilight, and I had never been struck as now by the simple beauty of the “ranges.” I would have liked to linger there for years, but we had to leave, one always has to leave, no matter what or where. And then, what would I have done at the University? Where is my place? Where am I going to live? Where am I going to die? (Diary: 1928-1957 113).

Julien Green in his productive old age. (Source)

Thank you for this wonderful tribute to a man who changed my life (for the better, I hope)! I devoted a chapter to him in my conversion memoir, An American Conversion: One Man’s Search for Truth and Beauty in a Time of Crisis (Rowman and Littlefield, 2004). I’ve read all of his books that have been translated, which is quite a few. My French, learned to pass an exam, hardly suffices! I will send you a photograph of the note he wrote to me in response to mine to him.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Pingback: Julian Green in Klagenfurt | Sancrucensis

Pingback: Elsewhere: More on Julien Green’s Life, Death, and Love of God | The Amish Catholic

Pingback: The Year’s Top Posts: 2017 | The Amish Catholic

I knew Julian Green and published an interview with him in THE GUARDIAN . (London) and wrote an introduction to his AVARICE HOUSE . Quartet 1991. To this day I still vividly remember him saying that he envied me my Catholic boyhood and being an altar boy as he converted too late… I really appeciate your article and you are right to praise LOVE IN AMERICA as it is one of the very best books about love between two people. I knew him in the late 80s and into the early 90s. I have a MA from Hollins College where I was a student 1969-70 with George Garrett who of course came abck to UVA

LikeLike