The COVID-19 crisis is impacting all of us at some level. Yet we are not alone in the midst of our fear and pain. In His grace, the Good Lord provides so many ways for us to grow in holiness in the midst of this affair. I offer a few ideas here for the general edification of the faithful.

- Offer up your suffering for the salvation and sanctification of sinners

The life of a Christian is the death of Christ. We can therefore unite all our sufferings – physical, emotional, mental – to the Cross. When we do so, we can impetrate tremendous graces for ourselves and others. If you are afflicted by the disease – offer it up. If you are worried for those you know who are ill – offer it up. If you are mourning – offer it up. If you are struggling with troubles related to work (or the lack thereof) – offer it up. If you are bored in quarantine – offer it up. Even minor inconveniences can become springs of grace when we offer them to the Great High Priest on high. A terrible crisis like the one we are now facing is also a marvelous opportunity to grow in holiness, to help others spiritually, and to nurture our abandonment to Divine Providence. Especially as we move through Lent. - Devote time to pious reading, especially of the Holy Scripture

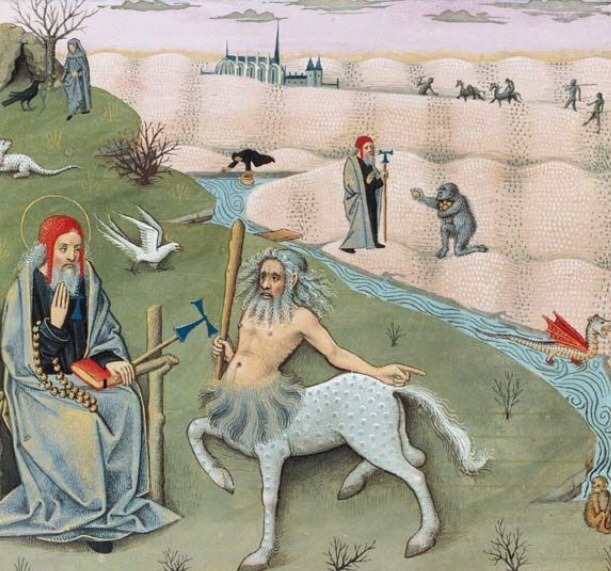

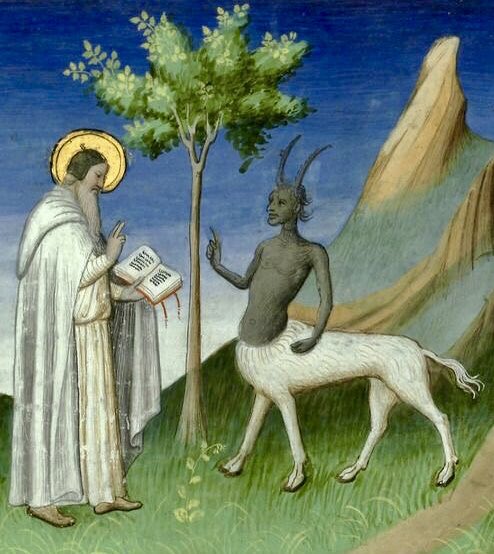

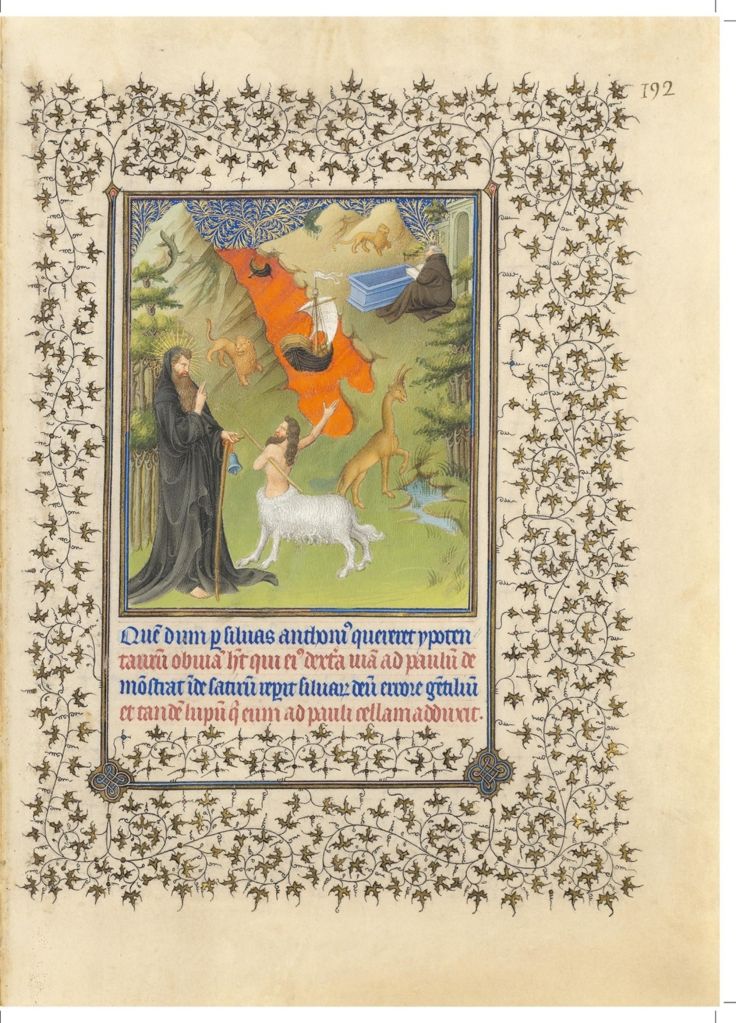

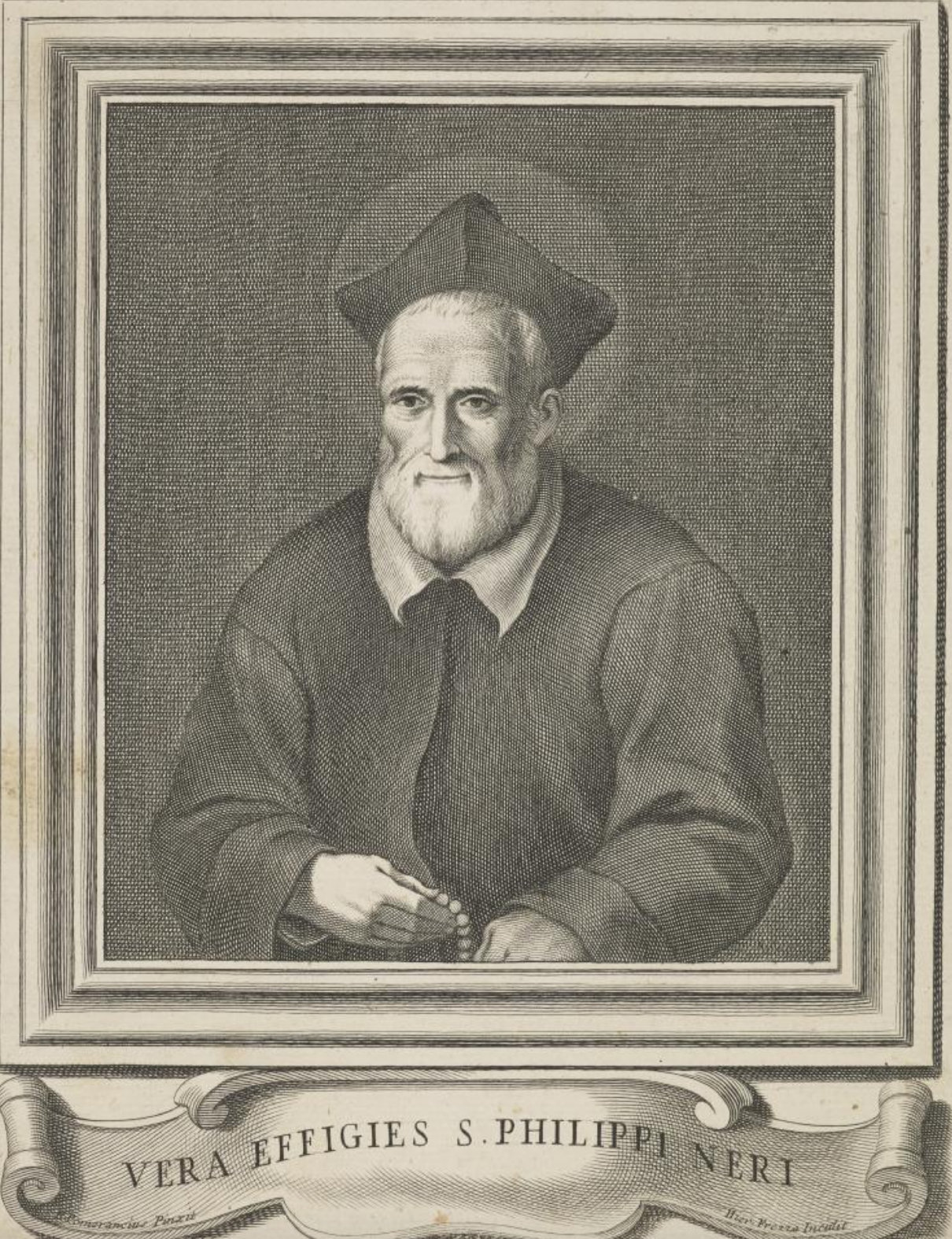

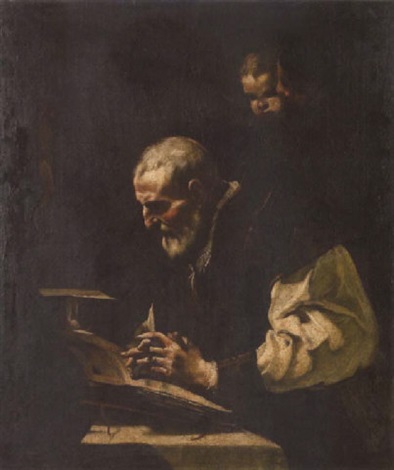

It is the duty of every Christian to be conversant with the Holy Scriptures, especially the Gospels. The stories and teachings of the Divine Physician may be especially comforting in this difficult time. On the other hand, I can hardly think of circumstance more apt to induce us to read the Prophecies and Apocalyptic books of the Bible. Beyond the Scriptures, one might turn to such edifying texts as In Sinu Jesu, All For Jesus, or Revelations of Divine Love. - Develop a friendship with one or more of the plague saints

There are many saints whom Catholics have called upon to help them in times of plague and pestilence. I listed a few here. You might find yourself drawn to St. Rosalia, or St. Sebastian, or St. Charles Borromeo. I have set up a candle in my own prayer corner dedicated to St. Roch. He has been a good intercessor for me in times past, and as the patron of bachelors (I am unmarried) and of animals (my family has many pets), I think he is a very appropriate saint to honor while I am stuck at home during this crisis. - Keep an extra day of special fasting, beyond Lenten Fridays

Wednesday was historically a day of penance in addition to Fridays. You might set aside Wednesday (or Thursday, in honor of the Blessed Sacrament, or Saturday, in honor of Our Lord’s entombment) as a sort of “second Friday.” You don’t have to give up meat; you could add an extra penance you only keep on this second day, such as giving up alcohol, or sweets, or praying an extra set of prayers. - Pray the Seven Penitential Psalms

The Divine Office is superior option to sanctify the hours, but for those who may lack the resources or time to do so, praying the Seven Penitential Psalms is a great alternative. Psalms 6, 31, 37, 50, 101, 129, and 142 (6, 32, 38, 51, 102, 130, and 143 for those of you using Protestant translations) are a moving, profound way to express sorrow for one’s own sins and for those of the whole world. - Pray the Rosary and the Divine Mercy Chaplet

These popular devotions are widely-known, so I won’t go on at length here about their peculiar merits. They are to be commended for their brevity, depth, and penitential character. Both are particularly well-suited to a time when we must implore God to spare us in His mercy. The Rosary also has the added benefit of beseeching the aid of the Queen of Heaven, whose title “Health of the Sick” comes to mind as particularly apropos in view of present circumstances. - Give to the poor and to religious houses

The lack of employment and an inability to leave the house is hitting working class families especially hard in this period, not to mention the homeless, prisoners, and others among society’s most vulnerable. I don’t yet know how to directly help them in a time of social distancing, but would be happy to take and/or post suggestions in the comments to this article. That said, I do know that religious houses will be struggling as well. Please consider giving to these holy souls, many of whom rely on charitable donations to get by month to month. I would direct my readers especially to the good Fathers and Brothers of Silverstream Priory. And don’t just give – pick up one of their excellent handmade decals, books, or prayers to Mother Mectilde de Bar from their online store! I’m sure the monks could use all the help they can get in this time of economic crisis. - Dedicate one hour daily to reparatory Adoration of the Most Blessed Sacrament through mental recollection

You don’t need to go to a chapel or church to adore the Blessed Sacrament. Set aside an hour in your day as a time of adoration. It need not distract from your work or recreation (though an extra hour of prayer may be a good idea, if it does not become too laborious). We can simply say to God, “I give you the next hour,” then come back to adore Him mentally through the hour as we can recall. And why not take the opportunity to make reparation for offenses against Our Eucharistic Lord, or His neglect in the tabernacles and altars of the world? This is a sweet and easy means to preserve the presence of God. Done regularly, it will help us grow in the sense of God’s proximity and in the trust of His merciful Providence. - Make a plague cross

Those who are feeling crafty might wish to draw or paint a version of one of the old plague crosses used in Europe during the late medieval and early modern periods. Examples abound online, as a quick Google search will reveal. This prayerful activity is not only a way to invoke the aid of great saints, but also a great way to connect with the history of Catholic devotion. - Intercede for the dead and dying

Fr. Faber recommends frequent, dedicated intercession for those in their last agony and for the holy souls of Purgatory. In a time of great mortality, it is an act of charity to pray in a special way for those who are succumbing to death. Indeed, praying for the dead is one of the seven spiritual works of mercy. You might begin by offering prayers for the dead and dying of your parish, then your diocese, then your state, then your nation, then the whole church, then the world. Let your prayer cast a wide net. - Make spiritual communions and acts of reparation each Sunday

This will, sadly, be necessary until public Masses are restored. But spiritual communions are not to be understood as somehow second-rate communions. When you are away from Mass in obedience to your bishop and through no fault of your own, you can still make a good communion with Our Lord. It may not possess the full sacramental character of a good Eucharistic communion, but it still binds us to the Eucharistic sacrifice. And any grace we receive as a result is indeed infused into us by the merits of Christ’s sacrifice. So let us come to love Acts of Spiritual Communion, an underappreciated and undervalued weapon in the Catholic arsenal in good times as well as in bad. You can find a variety all over the internet. I would add to these an Act of Reparation in time of plague. - Pray for the grace of final perseverance

St. Benedict teaches us that the Christian must “Keep death daily before one’s eyes” (Rule of St. Benedict, Chapter IV). In a time like this, it is hard not to follow this advice. And yet, we can put off the reality of our mortality by the unconscious assumption that it will never be us. Surely, death will pass us by. Surely, we have blood on our door. But the fact is, we don’t know when our time will come. The more seriously we take the prospect of our own mortality, the more shall we find ourselves drawn to ponder our own judgment. Let this salutary meditation induce us to pray for the graces of final repentance and perseverance and abandonment to the will of God.

And may the grace of Our Lord Jesus Christ, and the Love of God, and the Communion of the Holy Ghost, be with us all evermore. Amen.