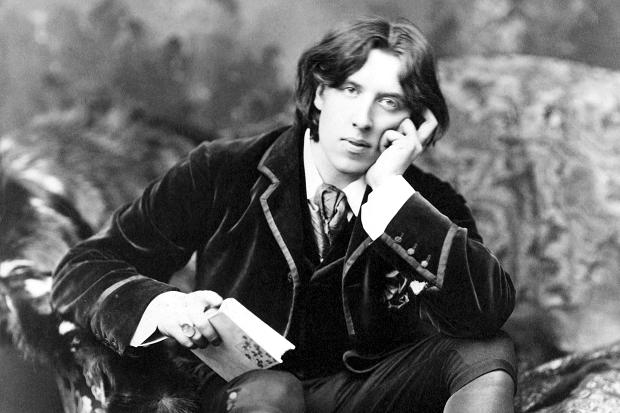

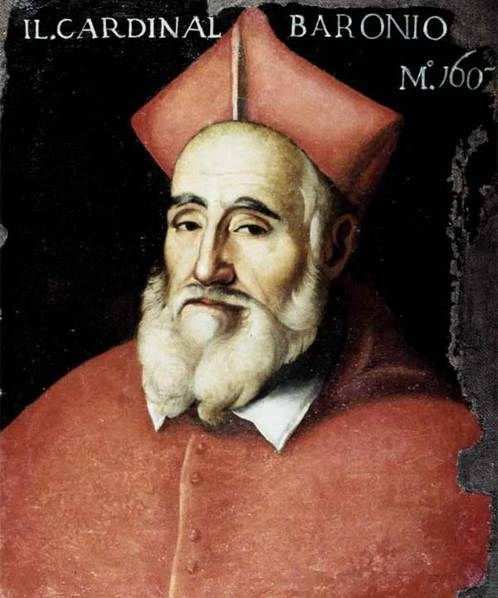

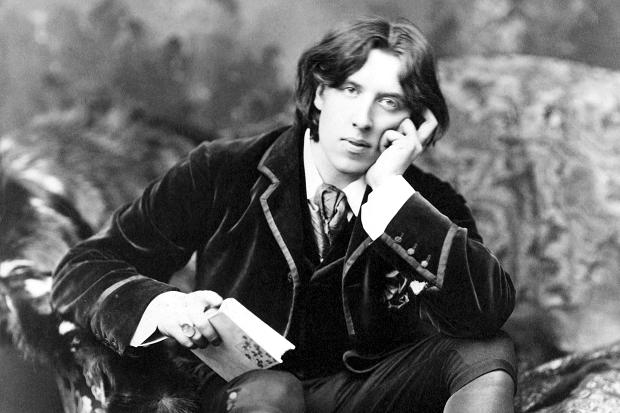

Oscar Fingal O’Flahertie Wills Wilde (Source).

As I mentioned in my last post, during the month of August, I am dedicating myself to daily acts of creativity in honor of Mary’s Immaculate and Sophianic Heart. As Providence would have it, the Holy Father’s intentions for August include prayers for artists. Thus, I’m going to make my blog especially aesthetic for the rest of the month.

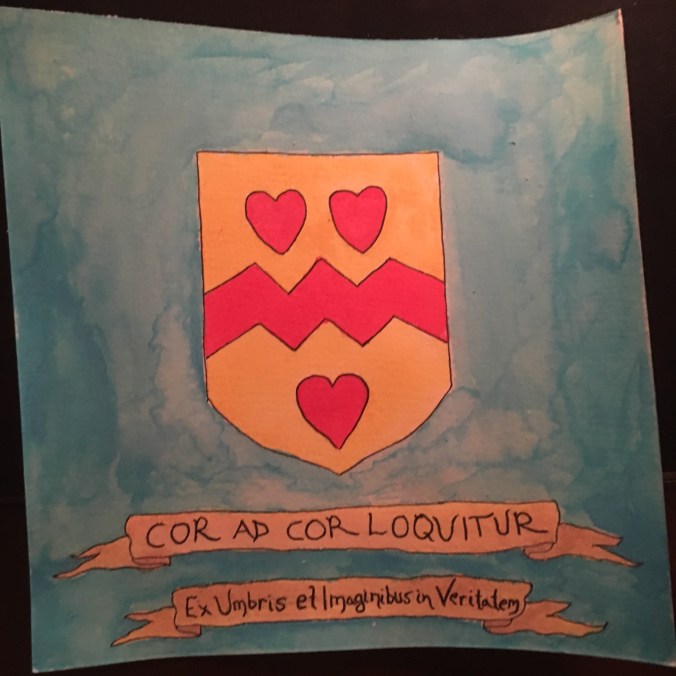

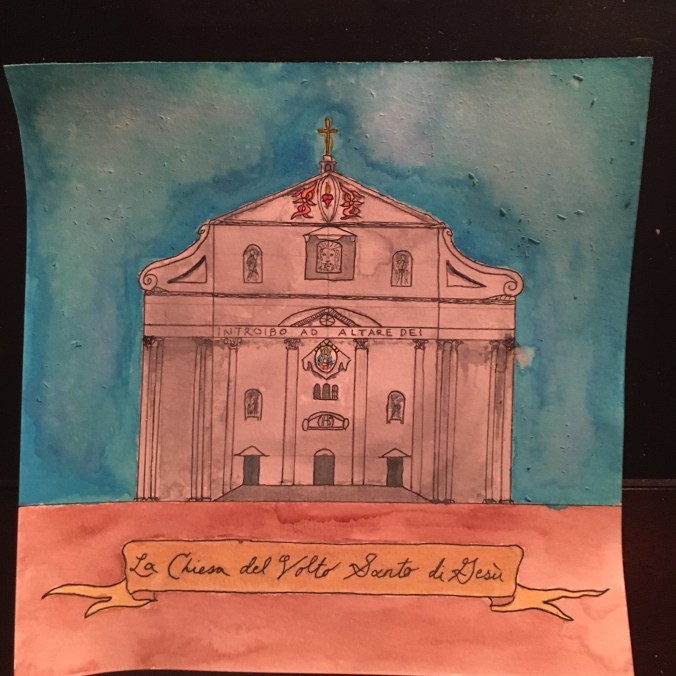

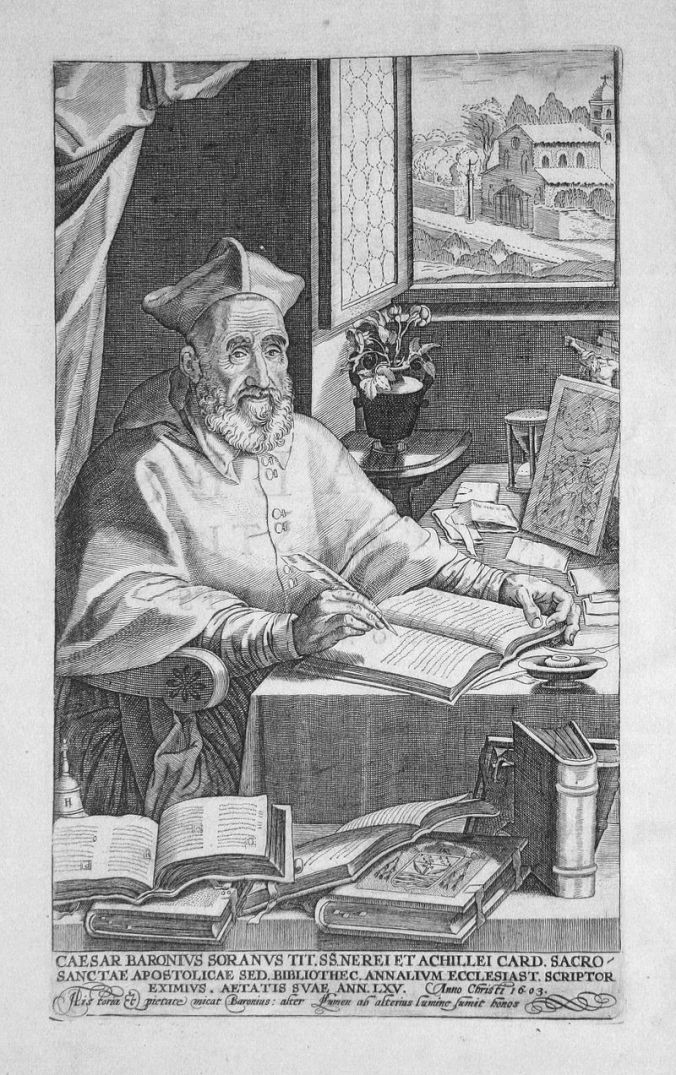

And what better way to start than examining work by one of the modern era’s great philosophers of art, Oscar Wilde? It is not often remembered today that Oscar Wilde was a Catholic. True, he was only formally received on his death bed. But Wilde maintained a lifelong flirtation with the faith. Catholicism infused his imagination from very early on in his productive career. When he was a student at Oxford, he visited Rome and wrote quasi-Catholic poetry that even Cardinal Newman admired. In some of the work, the influence of Dante is manifest. The aesthetics and romance of Catholicism appealed to Wilde, and he was nearly converted by Fr. Sebastian Bowden of the London Oratory. Only much later did he definitively turn to the Lord, in his last hour. However, many members of his circle also converted…a topic I shall, perhaps, explore some other day.

Ave Maria Gratia Plena

Was this His coming! I had hoped to see

A scene of wondrous glory, as was told

Of some great God who in a rain of gold

Broke open bars and fell on Danae:

Or a dread vision as when Semele

Sickening for love and unappeased desire

Prayed to see God’s clear body, and the fire

Caught her white limbs and slew her utterly:

With such glad dreams I sought this holy place,

And now with wondering eyes and heart I stand

Before this supreme mystery of Love:

A kneeling girl with passionless pale face,

An angel with a lily in his hand,

And over both with outstretched wings the Dove.

Sonnet on Approaching Italy

I reached the Alps: the soul within me burned

Italia, my Italia, at thy name:

And when from out the mountain’s heart I came

And saw the land for which my life had yearned,

I laughed as one who some great prize had earned:

And musing on the story of thy fame

I watched the day, till marked with wounds of flame

The turquoise sky to burnished gold was turned,

The pine-trees waved as waves a woman’s hair,

And in the orchards every twining spray

Was breaking into flakes of blossoming foam:

But when I knew that far away at Rome

In evil bonds a second Peter lay,

I wept to see the land so very fair.

Urbs Sacra Æterna

Rome! what a scroll of History thine has been

In the first days thy sword republican

Ruled the whole world for many an age’s span:

Then of thy peoples thou wert crownèd Queen,

Till in thy streets the bearded Goth was seen;

And now upon thy walls the breezes fan

(Ah, city crowned by God, discrowned by man!)

The hated flag of red and white and green.

When was thy glory! when in search for power

Thine eagles flew to greet the double sun,

And all the nations trembled at thy rod?

Nay, but thy glory tarried for this hour,

When pilgrims kneel before the Holy One,

The prisoned shepherd of the Church of God.

Sonnet on Hearing the Dies Irae Sung in the Sistine Chapel

Nay, Lord, not thus! white lilies in the spring,

Sad olive-groves, or silver-breasted dove,

Teach me more clearly of Thy life and love

Than terrors of red flame and thundering.

The hillside vines dear memories of Thee bring:

A bird at evening flying to its nest

Tells me of One who had no place of rest:

I think it is of Thee the sparrows sing.

Come rather on some autumn afternoon,

When red and brown are burnished on the leaves,

And the fields echo to the gleaner’s song,

Come when the splendid fulness of the moon

Looks down upon the rows of golden sheaves,

And reap Thy harvest: we have waited long.

Holy Week at Genoa

I wandered through Scoglietto’s far retreat,

The oranges on each o’erhanging spray

Burned as bright lamps of gold to shame the day;

Some startled bird with fluttering wings and fleet

Made snow of all the blossoms; at my feet

Like silver moons the pale narcissi lay:

And the curved waves that streaked the great green bay

Laughed i’ the sun, and life seemed very sweet.

Outside the young boy-priest passed singing clear,

‘Jesus the son of Mary has been slain,

O come and fill His sepulchre with flowers.’

Ah, God! Ah, God! those dear Hellenic hours

Had drowned all memory of Thy bitter pain,

The Cross, the Crown, the Soldiers and the Spear.

San Miniato

See, I have climbed the mountain side

Up to this holy house of God,

Where once that Angel-Painter trod

Who saw the heavens opened wide,

And throned upon the crescent moon

The Virginal white Queen of Grace,–

Mary! could I but see thy face

Death could not come at all too soon.

O crowned by God with thorns and pain!

Mother of Christ! O mystic wife!

My heart is weary of this life

And over-sad to sing again.

O crowned by God with love and flame!

O crowned by Christ the Holy One!

O listen ere the searching sun

Show to the world my sin and shame.

Madonna Mia

A lily-girl, not made for this world’s pain,

With brown, soft hair close braided by her ears,

And longing eyes half veiled by slumberous tears

Like bluest water seen through mists of rain:

Pale cheeks whereon no love hath left its stain,

Red underlip drawn in for fear of love,

And white throat, whiter than the silvered dove,

Through whose wan marble creeps one purple vein.

Yet, though my lips shall praise her without cease,

Even to kiss her feet I am not bold,

Being o’ershadowed by the wings of awe.

Like Dante, when he stood with Beatrice

Beneath the flaming Lion’s breast, and saw

The seventh Crystal, and the Stair of Gold.

E Tenebris

Come down, O Christ, and help me! reach thy hand,

For I am drowning in a stormier sea

Than Simon on thy lake of Galilee:

The wine of life is spilt upon the sand,

My heart is as some famine-murdered land,

Whence all good things have perished utterly,

And well I know my soul in Hell must lie

If I this night before God’s throne should stand.

‘He sleeps perchance, or rideth to the chase,

Like Baal, when his prophets howled that name

From morn to noon on Carmel’s smitten height.’

Nay, peace, I shall behold before the night,

The feet of brass, the robe more white than flame,

The wounded hands, the weary human face.

At Verona

How steep the stairs within Kings’ houses are

For exile-wearied feet as mine to tread,

And O how salt and bitter is the bread

Which falls from this Hound’s table,–better far

That I had died in the red ways of war,

Or that the gate of Florence bare my head,

Than to live thus, by all things comraded

Which seek the essence of my soul to mar.

‘Curse God and die: what better hope than this?

He hath forgotten thee in all the bliss

Of his gold city, and eternal day’–

Nay peace: behind my prison’s blinded bars

I do possess what none can take away,

My love, and all the glory of the stars.

On the Massacre of the Christians in Bulgaria

Christ, dost Thou live indeed? or are Thy bones

Still straitened in their rock-hewn sepulchre?

And was Thy Rising only dreamed by her

Whose love of Thee for all her sin atones?

For here the air is horrid with men’s groans,

The priests who call upon Thy name are slain,

Dost Thou not hear the bitter wail of pain

From those whose children lie upon the stones?

Come down, O Son of God! incestuous gloom

Curtains the land, and through the starless night

Over Thy Cross a Crescent moon I see!

If Thou in very truth didst burst the tomb

Come down, O Son of Man! and show Thy might

Lest Mahomet be crowned instead of Thee!

Queen Henrietta Maria

In the lone tent, waiting for victory,

She stands with eyes marred by the mists of pain,

Like some wan lily overdrenched with rain:

The clamorous clang of arms, the ensanguined sky,

War’s ruin, and the wreck of chivalry,

To her proud soul no common fear can bring:

Bravely she tarrieth for her Lord the King,

Her soul a-flame with passionate ecstasy.

O Hair of Gold! O Crimson Lips! O Face

Made for the luring and the love of man!

With thee I do forget the toil and stress,

The loveless road that knows no resting place,

Time’s straitened pulse, the soul’s dread weariness,

My freedom and my life republican!

On Easter Day

The silver trumpets rang across the Dome:

The people knelt upon the ground with awe:

And borne upon the necks of men I saw,

Like some great God, the Holy Lord of Rome.

Priest-like, he wore a robe more white than foam,

And, king-like, swathed himself in royal red,

Three crowns of gold rose high upon his head:

In splendor and in light the Pope passed home.

My heart stole back across wide wastes of years

To One who wandered by a lonely sea,

And sought in vain for any place of rest:

“Foxes have holes, and every bird its nest,

I, only I, must wander wearily,

And bruise My feet, and drink wine salt with tears.”

Wilde did just that until he lost his duel with the wallpaper on November 30th, 1900. But having received the last rites of the Church, perhaps he is already in heaven as a saint. One can only imagine what he would think of his portrait bedecked with a golden halo.