The official drink of the movement. (Source)

By now, it has become a commonplace among the Catholic literati that, as one reporter put it, “The Kids are Old Rite.” Traditionalism is on the rise among Millennial Catholics. Several overlapping clans of young, traditional Catholicism have arisen over social media, especially Twitter. Traditional orders get more and younger vocations; older, more progressive orders face extinction in the near future. The Pope himself has taken notice and expressed concerns about this trend. Of course, most of the young trads prefer a pope closer to their own age.

Several unrelated items recently have come up in my news-feed that have collectively crystallized the issue for me.

I

First, a three-part study of FOCUS (The Fellowship of Catholic University Students) has just appeared in the National Catholic Reporter. While I’m often wary of NCR’s coverage on just about anything, I’d encourage you to read it. Sometimes the magazine’s liberal bias gets the best of it, as in a mostly uninteresting examination of FOCUS’s ties to Neo-Conservative and generally right-wing organizations in Part II.

But there are also genuine insights. A lot of the issues raised reminded me of my own somewhat mixed experience with a FOCUS-dominated campus ministry. I certainly made friends, some of whom I still consider important mentors. My first-year Bible Study leader, a fellow student who had been “discipled” by the FOCUS missionaries, was a great influence in my first year of Catholicism (and beyond). But I more or less left the ministry fairly early on, like most of my trad or trad-lite friends. The NCR study gets into some of the reasons why.

For instance, in Part 1, we read:

A FOCUS women’s Bible study group gave Elisa Angevin purpose and strengthened her values — at first. As a freshman at New York University, she met a missionary, who became a mentor and a friend.

But as she met different people outside that community — some of whom were “rubbed the wrong way” by FOCUS — Angevin began to distance herself from the group because it felt exclusionary, rigid and not open to different ways of being Catholic.

“Once you become part of FOCUS, it has a very structured approach,” recalled Angevin, now 25 and a social worker in New York. “It created a lot of passion. But a lot of student leaders looked down on other people who didn’t have the same passion.”

Angevin attended some of FOCUS’ mega-conferences, such as the Student Leadership Summit, and was inspired by the speakers and sense of community. “It was empowering to see people my age who were as excited as I was,” Angevin recalled. “But as I started to get older, the newness had worn off … and it felt very closed.”

A lot of this rings true. Speaking from my own experience, I always got the very strong impression that FOCUS represented a fairly “mainstream” form of Catholicism, the JP2 consensus. Banal liturgy coupled with social conservatism. But there really isn’t any room for traditionalists – or even just those who are friendly to the Old Mass and the piety it sustained. I remember being called “judgmental” for my views. Other trads were sidelined as well.

I also think that the program’s reliance on *very young* missionaries often leads to a dumbing-down of the vast spiritual and intellectual inheritance that is Catholicism. There’s some call for this at a campus ministry, where ministers have to reach as many people as possible. Not everyone can or even should be St. Thomas Aquinas. Undergraduates don’t often go to ministries looking for lectures, but for some escape from the academic life. Still, must it all be so infantilizing? Perhaps you can see what I mean here:

At the Chicago event, held at the sprawling McCormick Place convention center, FOCUS founder Curtis Martin struts onto the stage, hands in the air, shouting “Woo!” and “Awesome!” to the applauding summit attendees who had been enjoying a contemporary Christian band before his keynote address. Two days earlier, actor Jim Caviezel — Jesus in the Mel Gibson film “The Passion of the Christ” — made a surprise visit to the conference.

“This is how awesome you are,” Martin said. “When the guy who pretended to be Jesus walked in the room, you all stood up and clapped, but when Jesus showed up, you all fell down and knelt. You know the difference. How cool is that?”

What an ineffably stupid way of addressing adults. Mr. Martin manages to strike at once a patronizing and self-congratulatory tone, a true rhetorical feat.

One thing I learned in the NCR articles is that FOCUS missionaries only get four weeks of training the summer before they begin. And some of that is dedicated to learning how to fund-raise. (Source)

Yet my unease with FOCUS wasn’t just with that sort of standard, if irritating, campus ministry procedure. As a recent convert who had grown up in an Evangelical Protestant school, I found a lot of FOCUS’s Protestant-lite discourse unsatisfying. It was more than just the use of emotivist praise and worship music at Benediction (as grating as that was). It was more than just the way FOCUS mission trips seemed to mirror the sort of make-work vacation mission trips I recognized from my time in the Evangelical world. I got the distinct sense that FOCUS borrowed heavily from the discourse of Evangelicalism, even down to the language it deployed when talking about conversion. Here’s an example from Part III:

As former FOCUS employees (called “missionaries”) or as students involved with the organization on their college campuses, they were taught its “Win, build, send” formula.

“Win” means to build “authentic friendships” with people, with the ultimate purpose of evangelization, while “build” requires helping those friends grow in faith and virtue through what FOCUS calls “the big three” virtues: chastity, sobriety and excellence.

First, we have the shallow reduction of evangelization to a business-like slogan, as if the work of the Holy Ghost could be charted like a marketing campaign. This type of lingo is, in my experience, very common in Evangelical discourse. Paired with it we find the language of authenticity. The first step in FOCUS’s three-part strategy is to “build ‘authentic friendships.'” Authenticity is like obscenity – you can’t define it, but you know it when you see it. The problem, of course, is that you can’t actually plan an “authentic friendship.” The planning is precisely what makes it artificial. Friendships come about organically, and no two look alike. The same can be said of conversions. At best, FOCUS should rather resemble what St. Philip Neri imagined the Oratory to be, though he never constructed any firm plans for the Congregation’s foundation or development. At worst, students get the sense of entering faux, farmed, and framed friendships. Those attract precisely no one.

In the emphasis on “chastity, sobriety, and excellence” as, risibly, “‘the big three’ virtues,” we find a synecdoche of the very strong note of philistine, puritanical prudery ensconced in FOCUS. Encountering this tendency also made me recall the moralistic Calvinism of my youth. Everything in Christianity seemingly came back to sex, drinking, and drugs. No one who ponders the state of American students could seriously suggest that these issues don’t matter, but to hammer on about them to the exclusion of two other triads – Faith, Hope, and Charity, and the Good, the True, and the Beautiful – makes Christianity dull.

Protestant Sunday worship, or Catholic conference? Hard to tell…and therein lies the rub. (Source)

But why does FOCUS make “chastity, sobriety, and excellence” its threefold mantra? The FOCUS promotional video in Part 1 offers some insight into their worldview. The narrative told there is one of nostalgia and decline. Various clips from the 1950’s are shown in contrast to the sex, drugs, technology, and mass media of today. The message is obvious: society was better back then, and it’s worse now. But it’s not fundamentally true. First of all, evil has always existed. FOCUS’s Manichaean view of the past may not be unusual, but it’s also deeply lopsided. All the terrible things FOCUS decries about our modern society – pornography, addiction, suicide, the disenchantment of consumerist technology – all of these things existed prior to the 1960’s. And lots of bad things about the society of the 1950’s have disappeared or been greatly mitigated in various ways (need I point out segregation as the elephant in the room?). Yet none of those advances are mentioned. It’s not surprising that social justice Catholics, like trads, find themselves ill at ease with FOCUS. Is it all that shocking that “a lack of racial, ethnic and economic diversity among students served by FOCUS is another criticism?”

The FOCUS video also fails to note the role the Church herself played in clearing the way for, hastening, and abetting the worst changes. Nary a peep do we hear about how leaders of the postconciliar Church abandoned her sacred mission to convert a sinful world, nor the way that such a surrender was intimately tied to the loss of the Mass of Ages.

I don’t intend for this post to be a simple laundry-list of my grievances with FOCUS, philosophical and otherwise. After all, I know plenty of wonderful people who got a lot out of their connection with the organization. The FOCUS missionaries themselves were always perfectly pleasant, and seemed orthodox enough. But I also knew others who felt excluded and patronized by the model they brought to campus ministry. I confess a very deep ambivalence about their hopes to expand ministry to parishes (though the veritable clerisy of middle-class lay ministers that Marti Jewell envisions in Part III of the report is hardly any better).

If we want to win the youth with “authenticity,” then look no further than the Latin Mass. Or even just the Novus Ordo celebrated according to Fortescue, as you see at the English Oratories. That which is unmistakably Catholic and orthodox has the best chance of bringing about conversion of heart. I would be curious to know how Juventutem compares to FOCUS in terms of outreach, vocations, etc. Regardless, my own view of how this program of evangelization might best function is in my essay, “The Oratorian Option.” Nothing has changed since then, except that I’ve gotten the chance to attend an Oratorian parish consistently, an experience that has corroborated my original theories. The Eucharist and the worthy celebration of the Mass are at the heart of it all.

It’s just unfortunate that FOCUS, at least as I’ve known them, aren’t interested.

II

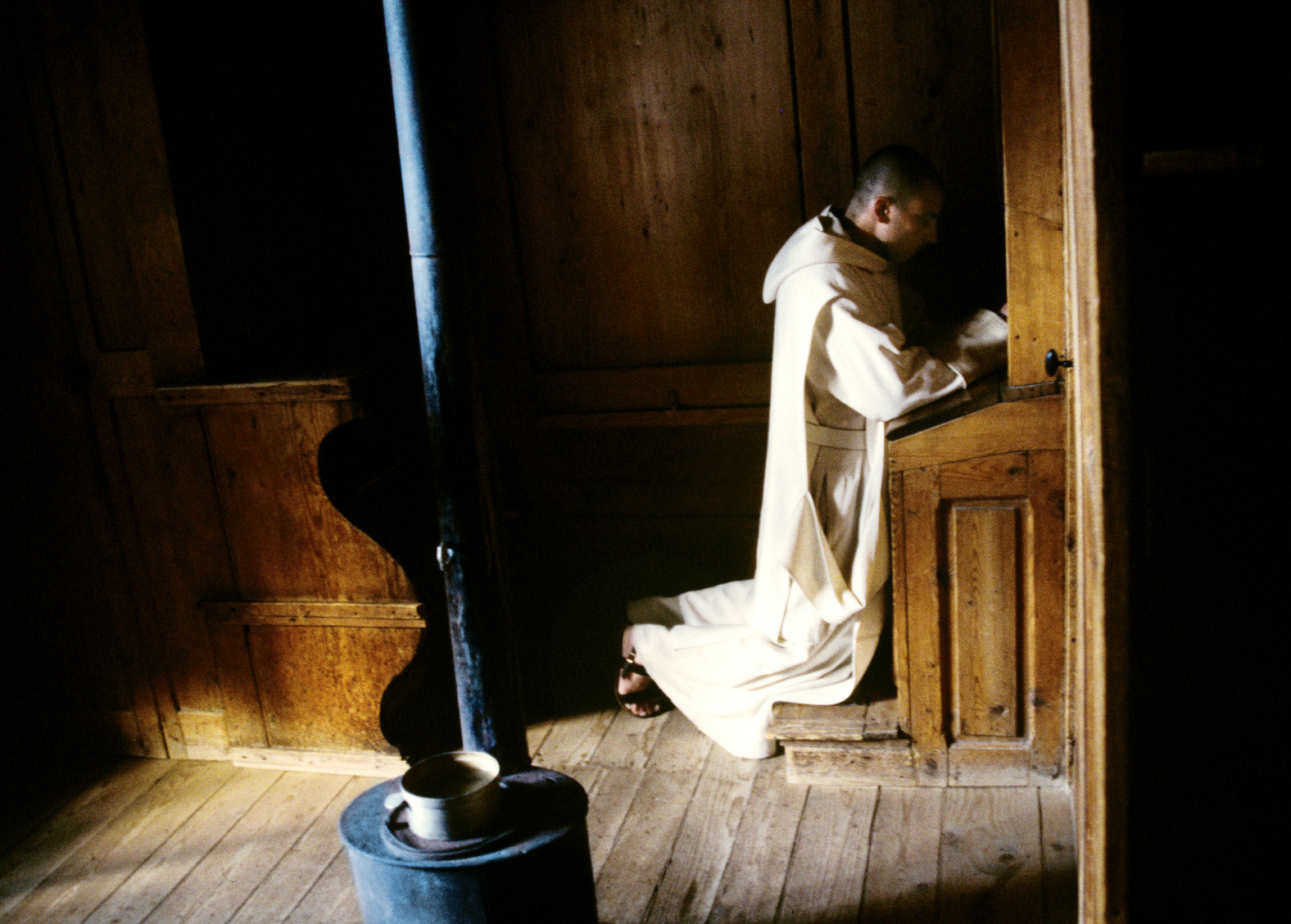

The New York Times published a piece on the Trappists of Mepkin, monks in my own home Diocese of Charleston. They’re good, quiet priests who farm mushrooms on a prime piece of real estate next to the Cooper River. The Times profile is nice enough, though I think its central flaws are aptly pointed out by my friend, Fr. Joseph Koczera SJ, in his response over at The City and the World. To wit:

Despite the NYT‘s suggestion that the Mepkin “affiliate program” represents “a new form of monasticism,” the monks themselves realize that it does not. As NYT reporter Stephen Hiltner observes, “the monks at Mepkin are cleareyed about the likelihood that their new initiatives — which will probably attract young, interfaith and short-term visitors — will fail to attract Roman Catholics who are interested in a long-term commitment with the core monastic community.” Mepkin’s abbot also frankly admits that the monastery may not survive: “I’d rather be in a community that has a vital energy and a good community life. And if that means closing Mepkin, that means closing Mepkin.”

“New” and dubiously monastic programs substituted for genuine, old-fashioned monasticism? We’ve seen this before. Mepkin’s well-intended program differs even from, say, the Quarr internship insofar as it isn’t primarily targeted to candidates who might plausibly have a vocation, single Catholic men from the ages of 18 to 25. And unlike Quarr, a monastery which retains its Solesmes heritage, Mepkin seems to be failing in part because it holds too tightly to the Spirit of the Council. Mepkin’s new affiliate program is open to women as well as men, “of any faith tradition.” It seems that the solution they’ve come up with to their vocational crisis is to become less Catholic, not more.

Fr. Koczera continues at length:

As Terry Mattingly points out at GetReligion, the NYT article is very one-sided, focusing on monasteries that are dying without ever asking questions about monasteries that actually are drawing vocations. Most Trappist monasteries in the United States seem to be in straits similar to those of Mepkin, at least judging by yearly statistics published by the Trappist Order. On the other hand, it isn’t difficult to find monasteries in the United States (albeit those of other orders) that continue to attract (and retain) young vocations: one thinks of the Benedictines at Our Lady of Clear Creek Abbey in Oklahoma or Saint Louis Abbey in Missouri, or of the Cistercian Abbey of Our Lady of Dallas (a monastery I’ve written about once or twice before)…Despite the evident sincerity of the monks at Mepkin Abbey, their sense of what young people want belies data about what young Catholics in particular are looking for. As the monks acknowledge, seeking to provide a haven for ‘spiritual but not religious’ types will not lead to an influx of new vocations. The monks may realize, too, that Millennial Catholics who take their faith seriously are also serious about commitment and likely to be unimpressed by a strategy that is specifically tailored to seekers who are “interested in the spiritual life journey, but not in institutional religion.” In this sense, it’s interesting to contrast the NYT story on Mepkin Abbey with a NBC News story from just last week that highlighted the rising number of American Millennials who are choosing to enter religious orders – and who enter looking for a solid sense of identity and commitment that is countercultural. They represent a generation of Catholics who find themselves, as Tracey Rowland writes, “in full rebellion from the social experiments of the contemporary era” as they seek “to piece together elements of a fragmented Christian culture.” Some will find the resources they need to assemble those fragments in one or another of America’s remaining monasteries – but not, it seems, at Mepkin Abbey.

A 2016 photo of the community of Norcia. The monastery is unlike Mepkin in many ways: young, international, augmented by regular vocations, and above all, Traditional. (Source)

Of the new monasteries that do seem to get vocations (and lots of them), two stand out: Norcia and Silverstream. The lives of these two monasteries are so attractive to young American Catholic men that, though they are in Italy and Ireland respectively, they are mostly inhabited by Americans willing to make the move to Europe. Both are old-rite monasteries. And I would wager that neither Dom Cassian Folsom nor Dom Mark Daniel Kirby went about planning their monastic ventures with catchy slogans or even a very programmatic sense of action. They celebrated the Mass reverently, preached orthodoxy, and, with the help of the internet, they achieved widespread fame. They shared the trust in Divine Providence that St. Philip had as he – or, in his own words, Our Lady – founded the Oratory.

III

My friend John Monaco has just published an excellent personal narrative at his blog, Inflammate Omnia. It describes his Catholic upbringing, difficulties in seminary, extended flirtation with liberalism, and final reversion to a basically Traditionalist position. Parts of it reminded me of my own story: my natural religious sentiment as a child, my vituperative liberalism in High School, my conversion and eventual move towards a more or less Traditionalist orientation, in part through the beneficent influence of the Christian East.

Christ offers us His heart freely and fully. (Source)

I was particularly taken with the way that the Act of Reparation to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, as traditional a devotion as you can get, gently shaped John’s sensibilities over time. His original resistance to the Sacred Heart gave way to the a love of Jesus in precisely this mystery. And by the infallible rule of Lex Orandi, Lex Credendi, the prayer also led him to adhere more perfectly to the Faith as enshrined in Tradition. He writes,

You see, the more I prayed to the Sacred Heart, the more I began to really think about what I was actually praying. Prayer of Reparation? “For what?” I asked. My sins. What does it mean to “resist the rights and teaching authority of the Church which Thou hast founded?” That must obviously mean that the Church has authority, and that Christ founded the Church. The more and more I prayed these prayers, the more I began to question its essence. And even more so, I began to question my own conduct and dispositions.

You see, none of this “mercy” stuff makes sense if we don’t believe that sin actually harms. If all sin is simply personal weaknesses that do not affect our relationship with God and each other, then why do we need forgiveness? Or, in response to some moral theologians, if it is impossible to sin, then what is the purpose of grace? If the Church doesn’t have authority, then why do we consider the command to preach the Gospel? If Christ didn’t found the Church, then why should we bother following it? I also wondered why I was skipping all of the “hard-sayings” of Jesus, such as His words on divorce and remarriage, purity, suffering, obedience, and the promise that the “world” would hate me for preaching the truth. I started examining the fact that people would tell me, “I like you because you’re not talking about Hell and all of that sin stuff all the time”, and that had less to do with me balancing the Christian message than it did with me picking & choosing which parts to speak about.

John also captures the essence of the new, young Traditionalism:

Delving beyond the contemporary face of Catholicism, I was able to re-discover Tradition- not through EWTN or Rorate Caeli, nor through PrayTell or Crux, but rather through a true experience of the sacred liturgy, prayer, and study.

A future church historian will take that line as summative of the entire experience of a generation. The only thing I would add is that in my own case, as with many others, beauty was the central thing. Community, tradition, stability, a sense of history; all these are goods that the Church offers her children. But it was supernatural beauty that captured my imagination and led me to a genuine encounter with the Living God. The Church has the chance to re-present that “beauty ever ancient, ever new” each week at the Mass. It is Christ Himself in the Eucharist who will convert the world. Not our misbegotten, if earnest, attempts to plan out the advance of His Kingdom. If anything, we too often get in His way.

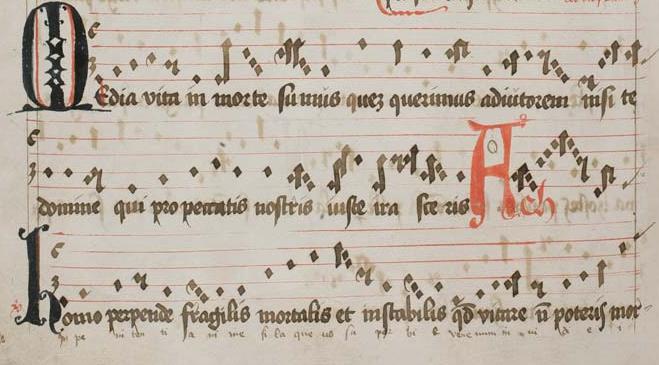

More of this, please. (Source)