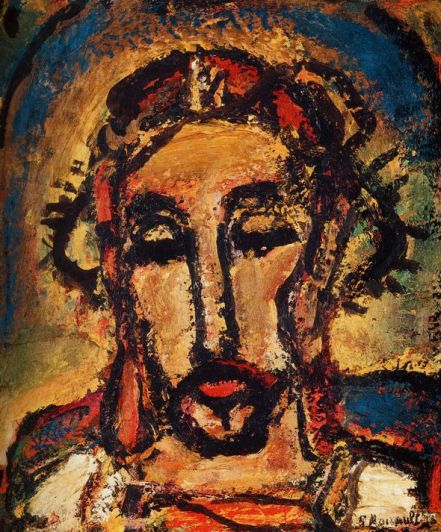

“Ecce Homo,” Georges Rouault. Vatican Museum. Rouault is an artist totally captivated by the beauty of the Holy Face.

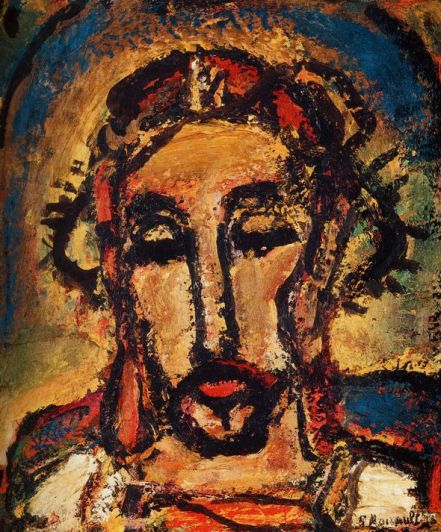

“Ecce Homo,” Georges Rouault. Vatican Museum. Rouault is an artist totally captivated by the beauty of the Holy Face.

Icon of the Transfiguration, by the hand of the great 15th century iconographer of Moscow, Theophanes the Greek.

Jesus took Peter, James, and John his brother, and led them up a high mountain by themselves. And he was transfigured before them; his face shone like the sun and his clothes became white as light. And behold, Moses and Elijah appeared to them, conversing with him. Then Peter said to Jesus in reply, “Lord, it is good that we are here. If you wish, I will make three tents here, one for you, one for Moses, and one for Elijah.” While he was still speaking, behold, a bright cloud cast a shadow over them, then from the cloud came a voice that said, “This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased; listen to him.” When the disciples heard this, they fell prostrate and were very much afraid. But Jesus came and touched them, saying, “Rise, and do not be afraid.” And when the disciples raised their eyes, they saw no one else but Jesus alone.

As they were coming down from the mountain, Jesus charged them,”Do not tell the vision to anyone until the Son of Man has been raised from the dead.”

These words from St. Matthew were the Gospel reading at Mass last night. Yesterday was the second weekend of Lent, and the Church directs our eyes, alongside those of the holy apostles, to the face of Our Lord in His Transfiguration. And in the Eastern Churches, today is St. Gregory Palamas Sunday. Palamas is most famous for his articulation of the Essence-Energies distinction as part of a broader polemic against the Byzantine Scholastic attacks on Hesychasm carried out by Barlaam of Seminara. One of Palamas’ key Scriptural examples of God’s energies is the “uncreated light” of Christ’s glory in the Transfiguration. St. Gregory is celebrated to this day by the Eastern Orthodox and by Eastern Catholics on their Lenten calendars; yet in the post-Scholastic West, he still holds no place on the calendar. I must wonder whether or not the readings for the Second Sunday of Lent were chosen at the revision of the Lectionary in part as an ecumenical gesture to the Orthodox, though my knowledge of 20th century liturgical innovations is shallow at best. Regardless, those who, to adapt a phrase of Pope St. John Paul II, “breathe with both lungs” of the Church can recognize the Providential coincidence of these two celebrations.

The Light of Tabor is, in a Palamite reading, the eternal Glory of God made manifest in, with, and through Christ’s created humanity. The Transfiguration is therefore an archetypal moment for every mystic—not just the Hesychasts whom St. Gregory was defending. In view of all this, while I listened to the priest reading the Gospel this evening, a song came to mind: “My Heart’s in the Highlands,” by Arvo Pärt. The lyrics are taken from a poem by Robert Burns. Here’s the chorus:

My heart’s in the Highlands, my heart is not here,

My heart’s in the Highlands, a-chasing the deer;

Chasing the wild-deer, and following the roe,

My heart’s in the Highlands, wherever I go.

A few weeks ago, when I first listened to the song, it immediately struck me as a potent metaphor for the contemplative life. Is not the contemplative’s heart set in the “high lands” of the spirit, like St. John of the Cross’s Mount Carmel? And has the Divine not been associated with wild deer throughout history, from the panting hart of Psalm 42 to the vision of St. Hubert to the White Stag of Narnia? The Apostles, like the mystics, like the chanting voice in Pärt’s song, are “led…up a high mountain by themselves.” There, they find Christ’s true glory, the energy of His divinity totally interpenetrating all they can perceive of him. The created rises into the divine, and the uncreated bends towards the creaturely; the two meet in the transfigured Christ. The dual presence of the heavenly Elijah and the Sheol-bound Moses demonstrates the moment of radiant communion between God and His creation, manifested perfectly in Christ, the Word made flesh.

Pärt’s song describes the experience of the mystic, not because Burns’ words actually refer to contemplation, but because of the way he takes up the verse and stretches it against an agonizingly poignant organ composition. He sets secular words to sacred music. Thus he accomplishes in miniature the assumption of the creaturely by the divine that comes before our vision in the Transfiguration. Art at its finest is called to participate in this lesser Transfiguration, and Pärt is a consummate master of what Tolkien might call “sub-creation.”

But Pärt is not alone in this; one of his colleagues, John Tavener, arguably a finer and more mystically-oriented composer, also transfigured profane writings into sacred pieces of music. I can think of no better example of this than his brief and delightful motet, “The Lamb.” Tavener took the lyrics from William Blake’s poem of the same name. In full, it reads:

Little lamb, who made thee

Dost thou know who made thee,

Gave thee life, and bid thee feed

By the stream and o’er the mead;

Gave thee clothing of delight,

Softest clothing, woolly, bright;

Gave thee such a tender voice,

Making all the vales rejoice?

Little lamb, who made thee?

Dost thou know who made thee?

Little lamb, I’ll tell thee;

Little lamb, I’ll tell thee:

He is callèd by thy name,

For He calls Himself a Lamb.

He is meek, and He is mild,

He became a little child.

I a child, and thou a lamb,

We are callèd by His name.

Little lamb, God bless thee!

Little lamb, God bless thee!

Here too, we might glimpse the transfigured Lamb of God between the lines of Blake’s verse. The lamb’s “clothing of delight/Softest clothing, woolly, bright” seems to echo the robe rendered “white as light” on Mt. Tabor. Blake speaks of “the vales” when Scripture instead would bring us up to the peaks. And the question that ends the first verse is fundamentally the same as that which must have run through the minds of the bewildered apostles; who is this man? The answer, of course, comes from the voice in the cloud: “This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased; listen to him.” And Tavener’s eerily beautiful choral setting imbues the lyrics with a dimension hitherto unimagined. Many of his works remind one of candlelight on ritual gold, or the smell of incense flying forth with the rhythm of thurible bells, or the echo that thins out asymptotically under the glittering mosaic of a high dome. “The Lamb” is all of this, presented compactly. It stands as one of his finest works, and one of his most spiritually rich.

I recently wrote about the Holy Minimalists in a piece on the music of The Young Pope. They’ve been on my mind. But I didn’t connect their artistic project to the Transfiguration until tonight. We Christians are to become “little Christs,” imitating Jesus in all things by adoption and deification. Sometimes, that takes the form of contemplation. The apostles model that path for us in their behavior on Mt. Tabor. But at other times, and in other ways, we are called to live the life of Christ more directly. The Transfiguration provides a mystical glimpse of what happens—and indeed, what will happen—when the uncreated Light of God assumes, permeates, and glorifies the creation. Of course, the energies of God are not found in the artifices of men; but artists can practice their own, creaturely form of transfiguration. The pieces of music I have discussed are shot through with an awareness of the divine presence, and the words that began as profane poetry become something altogether different, something sacred, something nearly liturgical.

At the beginning of Lent, T.S. Eliot tells us to “Redeem/The time.” On this, the Second Sunday of the penitential season, Christ reveals in Himself how we might do so—a transfiguration that Arvo Pärt and John Tavener have achieved, in some small way, through their own creative work.

T.S. Eliot’s “Ash Wednesday,” first edition cover. Source: Wikimedia.

Today is Ash Wednesday, and once again my thoughts turn to T.S. Eliot. Later, I will listen, as I used to do after all my confessions, to the Pope of Russell Square intone “Ash Wednesday” (1930) in a vatic voice. Like Eliot, I am a convert. And for all converts, Ash Wednesday offers a reminder of the life we have left behind. Converts feel, perhaps more powerfully than those raised in the faith, the strange liminal state of the Christian life. We are dead to sin, but not yet fully alive. The ashes imposed on our foreheads are merely the outward sign of an ever-fragile conversion. Ash Wednesday is the reminder of our weakness, of our constant need for mercy, of the vast landscapes of heaven and hell that open for us beyond the febrile veil of our brief hours on earth. On Ash Wednesday, we remember our death. Reversing all natural order, the penitential season begins with death and ends with the triumph of life. Let it never be said that the liturgical calendar lacks paradox. “Although I do not hope to turn again,” the liturgy leads me to do so.

As much as I love Eliot’s work, I don’t think his fine poem is the only one worth reading today. I might also consider the work of another great Anglican writer, George Herbert.

George Herbert (1593-1633). Source: New Statesman

In The Temple (1633), Herbert devotes one of his poems to Ash Wednesday. He writes, in a detached style that marks him as perhaps the preeminent pastor-poet of Anglicanism:

Welcome deare feast of Lent: who loves not thee,

He loves not Temperance, or Authoritie,

But is compos’d of passion.

The Scriptures bid us fast; the Church sayes, now:

Give to thy Mother, what thou wouldst allow

To ev’ry Corporation.

Herbert, like Eliot so many centuries later, is a writer of deeply ecclesial sensibilities. His poetic is shaped by the language of the Prayer Book and the Bible, at once homely and hieratic. Yet his moral vision clearly grows from his practical experience as a vicar. One could be forgiven for mistaking the poem for a sermon in verse.

True Christians should be glad of an occasion

To use their temperance, seeking no evasion,

When good is seasonable;

Unlesse Authoritie, which should increase

The obligation in us, make it lesse,

And Power it self disable.

Besides the cleannesse of sweet abstinence,

Quick thoughts and motions at a small expense,

A face not fearing light:

Whereas in fulnesse there are sluttish fumes,

Sowre exhalations, and dishonest rheumes,

Revenging the delight.

Throughout, he tempers his characteristic calls for conversion with a profound humility before the perfection of Christ. To conclude:

Who goeth in the way which Christ hath gone,

Is much more sure to meet with him, than one

That travelleth by-ways:

Perhaps my God, though he be far before,

May turn, and take me by the hand, and more

May strengthen my decays.

Yet Lord instruct us to improve our fast

By starving sin and taking such repast

As may our faults control:

That ev’ry man may revel at his door,

Not in his parlor; banqueting the poor,

And among those his soul.

Out of Catullus

By Richard Crashaw (translating Catullus)

As shall mocke the envious eye.

Sonnet 29

By William Shakespeare

When, in disgrace with fortune and men’s eyes,

I all alone beweep my outcast state,

And trouble deaf heaven with my bootless cries,

And look upon myself, and curse my fate,

Wishing me like to one more rich in hope,

Featur’d like him, like him with friends possess’d,

Desiring this man’s art and that man’s scope,

With what I most enjoy contented least;

Yet in these thoughts myself almost despising,

Haply I think on thee, and then my state,

Like to the lark at break of day arising

From sullen earth, sings hymns at heaven’s gate;

For thy sweet love remember’d such wealth brings

That then I scorn to change my state with kings.

The Flaming Heart

By Richard Crashaw (excerpted)

O heart, the equal poise of love’s both parts,

Big alike with wounds and darts,

Live in these conquering leaves; live all the same,

And walk through all tongues one triumphant flame;

Live here, great heart, and love and die and kill,

And bleed and wound, and yield and conquer still.

Let this immortal life, where’er it comes,

Walk in a crowd of loves and martyrdoms;

Let mystic deaths wait on ’t, and wise souls be

The love-slain witnesses of this life of thee.

O sweet incendiary! show here thy art,

Upon this carcass of a hard cold heart,

Let all thy scatter’d shafts of light, that play

Among the leaves of thy large books of day,

Combin’d against this breast, at once break in

And take away from me my self and sin;

This gracious robbery shall thy bounty be,

And my best fortunes such fair spoils of me.

O thou undaunted daughter of desires!

By all thy dow’r of lights and fires,

By all the eagle in thee, all the dove,

By all thy lives and deaths of love,

By thy large draughts of intellectual day,

And by thy thirsts of love more large than they,

By all thy brim-fill’d bowls of fierce desire,

By thy last morning’s draught of liquid fire,

By the full kingdom of that final kiss

That seiz’d thy parting soul and seal’d thee his,

By all the heav’ns thou hast in him,

Fair sister of the seraphim!

By all of him we have in thee,

Leave nothing of my self in me:

Let me so read thy life that I

Unto all life of mine may die.

By John Donne

The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock

My blog has something to tell you

Ordos, reflections, and thoughts on prayer

"My friends at least will accept them as such, whether they like their collective title or not." - George MacDonald

Exploring the heterodox in science, religion, and politics

A blog dedicated to particularities of the Catholic liturgy in Portugal

séminaire de recherche de l'IRSE et du CERPHI

writing from the soul and the mind

billectric

Politics & Culture from a Catholic perspective

Historian, folklorist, indexer, and translator

"...like the sun he heated the world with the warmth of his virtues and filled it with the splendor of his teaching."

herstory. poetry. recipes. rants.

A site dedicated to exploring ruins of years gone by in South Carolina.

Publication + Consultancy. Championing creative talent before a mass audience. Passionately global.

The Desire for the Transcendent

and the Catholicate of the West

An Homage to Bolton Morris Church Artist 1920-2004

Everything Catholic Today

Dixitque Deus, "Fiat lux", et facta est lux

Helping young Catholic men seek Heaven.

An exploration of the works of poet Charles Williams (1886-1945)

An Open-Access, Peer-Reviewed Journal

Highly unusual lives.

‘Catholicity, Antiquity, and consent of the Fathers, is the proper evidence of the fidelity or Apostolicity of a professed Tradition’ J.H. Newman, Lectures on the Prophetical Office of the Church, 1837, p. 51