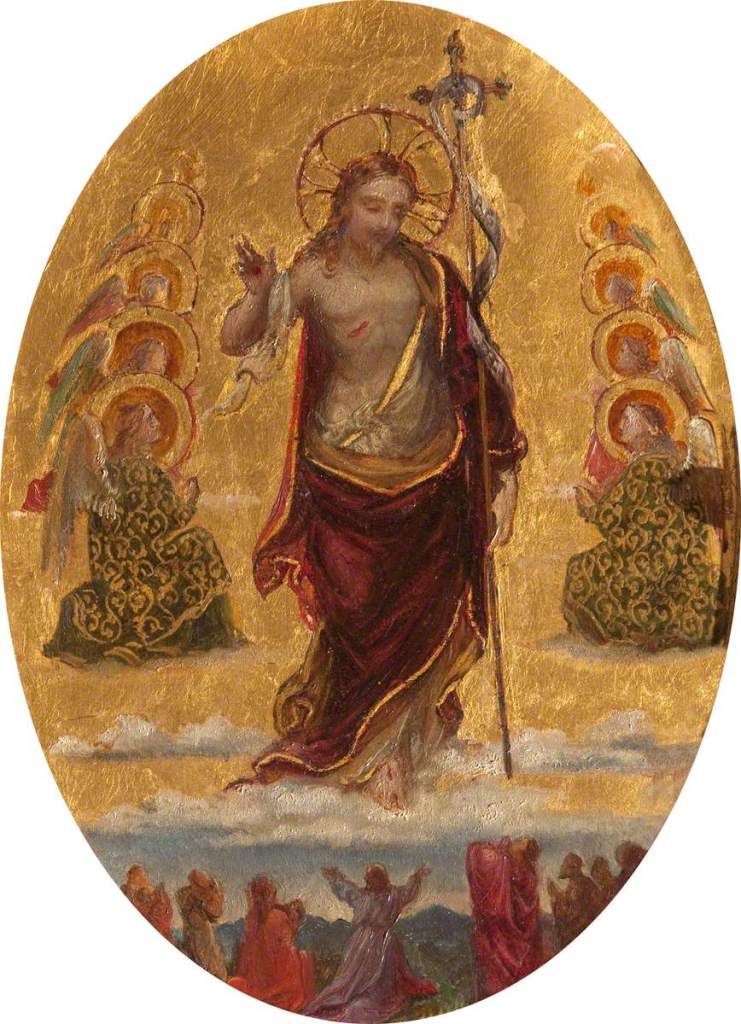

And he led them out as far as to Bethany, and he lifted up his hands, and blessed them. And it came to pass, while he blessed them, he was parted from them, and carried up into heaven. And they worshipped him, and returned to Jerusalem with great joy: And were continually in the temple, praising and blessing God. Amen. – Luke 24: 50-53

Many years ago, shortly after the start of my faith journey, I received some very good advice from an Anglican friend of mine. Or rather, I received a very good prayer. She told me that whenever she was anxious or worried or stressed about anything, she resorted to a prayer that ran like this:

“Jesus Christ is my High Priest, and He will always see me through.”

There is much consolation in these simple words, as I have had frequent occasion to learn in the years since then. And, to be honest, I am most drawn to Christ in the mystery of His High Priesthood. I often find myself asking Him to pray for me, not in the sense that one asks a friend or a saint to pray, but as one can only ask a sovereign and perfect intercessor. This sense of Christ as High Priest has become part of the basic structure of my own faith. Yet today’s feast, the Ascension of Our Lord into Heaven, invites us all to dwell upon this mystery in a more explicit way.

It is a curious fact of the Church’s kalendar that in those solemnities when she most fervently celebrates the Incarnation, she also insists most firmly upon the hiddenness of God. In Christmas, we observe Christ born in a lowly shed at night, disclosing His presence only to those shepherds who resemble Him in their poverty, humility, and obscurity. Today’s feast of the Ascension is composed of a similar doubling. It brings before our eyes the Incarnation in its most radical implications—while reminding us that we live in and with Christ’s apparent absence.

It is, therefore, a salutary lesson in the virtue of Faith. I think that we too often lose sight of what Faith really is. Scripture tells us: “Now faith is the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen” (Heb. 11:1 KJV). But what does this really mean?

God’s absence is felt in two ways. First, we feel it through the insistent reality of evil. The agony of the world we live in is too great, too universal, and too obvious to need any underlining. The Church is no different. How many malicious and mediocre priests seem to cloud the pure light of the Gospel! Their sin weighs more heavily, for they have been given a greater charge. Yet there is some comfort in the High Priesthood of Christ. If our earthly priests falter and fail, Christ never will. He remains forever a spotless offering in the sight of the Father, and His blood is all-cleansing. The invisible pontiff of an invisible, all-embracing, and everlasting temple, Christ never abandons His children, who linger below with expectant eyes.

Let us pass on to the second sense in which God hides Himself, leaving us with, in the words of R.S. Thomas,

this great absence

R.S. Thomas, “The Absence”

that is like a presence, that compels

me to address it without hope

of a reply.

The past is forever dead to us, an enormous absence, a distantly glimmering mirage that fades even as we approach it. Sacred History, even supported by texts and archaeology, is not a special case. There is a sense in which the facts of the Incarnation, Death, and Resurrection of Christ are no different here. We may participate in them, but we cannot directly experience them as historical events, in historical time.

So, what are we to do? How do we deal with the fact that God’s acts of revelation lie hidden behind the curtain of time? Quite simply, we must have faith. We must declare that faith is not certainty and not knowledge, but an engraced movement to trust those little lights given unto us. Those lights are, mainly, Scripture and Tradition, particularly the Liturgy, in which the Church as a body transcends the limits of earthly time through her collective remembrance. There is a tendency in Catholicism to downplay the “memorial” function of liturgy. This is a mistake. In fact, there is a sense in which the essence of the Liturgy (or rather, the Liturgies of the various Catholic Churches) is memory. But it is the memory of the Church as the very Body of Christ, a memory which realizes and re-presents the object of remembrance, not mere empty symbolism. Orthodox theologians have been better on this point than Western ones, perhaps because they have not been so fearful of the specter of Zwingli. But I digress.

All of this is to say that we cannot state with the certainty of historical science whether Sacred History is true. There is no real evidence for most of revelation, and we should not let the apologists delude us on this point. They’re far more addled by modernity than they realize. But by grace we can and should leap boldly across the chasm of our natural uncertainty, avoiding the Scylla of Apologetic Positivism and the Charybdis of Naturalistic Doubt. The result is not knowledge, which has no meaning here, but faith.

We would all be better off in a position of greater epistemological humility. For instance—let’s be honest—we have absolutely no knowledge of what happens after death. The data is inconclusive: annihilation, a flash of light, reincarnation, hauntings, purgatory, heaven and hell. We know nothing. It may seem like a commonplace, but it bears repeating, that our fate after death is a mystery. All we can do is have faith that what we have been promised is true. But none of this is certainty, not even for our own salvation. Do you know you will be saved? No. For no one can know what comes after death. Eternal hellfire or an infinity of mute blackness or a strange new human life could come instead. The only thing to do is to pray for mercy “in fear and trembling,” placing our faith in the Hidden God (Philip. 2:12).

Do not say to me that you “know” these things because you “know” your Bible or because you “know” Church teaching or even because you “know” Jesus. To be frank, I don’t believe it. In fact, I’m not confident we can know God at all, in the sense of positive knowledge. God’s existence is not like a mathematical theorem or the date of the Battle of Waterloo. Nor do I think you can know God or any of His saving mysteries like you can know another person. You cannot see God; you cannot touch Him; you cannot hear Him like you can hear a friend or lover or even a stranger passing in the street. Simply put, I don’t believe that our “knowledge” of God, the Infinite and loving ground of Being, should be called “knowledge” at all. In fact, I rather suspect that this fixation with “knowledge” has been a very substantial problem for the Church throughout her history.

To interject a personal note; I look back at my life and I sometimes wonder if I ever really knew Christ. There are others I doubt as well. False mystics and visionaries abound, as the Church chokes on her own prelest. But when I look at my own case, I remain unsure. I certainly know a lot about the Church, and have ever since I eagerly began RCIA nearly ten years ago. But did I know Christ? Was I just enamored with my own exaltation, with the fool’s-gold assurances of spiritual certainty, with the glittering baubles that float like empty bottles down the Tiber? Is it even possible to know Him? Or must we just choose, by grace, to have faith—to place our confidence in Him, trusting that He will guide us through the overwhelming darkness of uncertainty which is the very tissue of our lives?

I have come around to the latter position. The virtue of Faith has nothing to do with knowledge per se, and is as far from certainty as East from West. It is granted to us precisely because we lack certain knowledge of the immense realities it comprehends, and probably must by our very nature. Eliot writes in “Burnt Norton” that “Human kind/cannot bear very much reality.” We forget our weakness too easily.

Happily, the substance of our faith does not reside in the natural faculties of understanding. As Pascal says, “It is the heart which experiences God, and not the reason. This, then, is faith: God felt by the heart, not by the reason.” In a sense, the Ascension is the true beginning of the Christian faith in history, for it inaugurates our sensible separation from Christ. Our eyes grow dim, but not our hearts. The blindness of nature is transformed into sight by grace.

In Exodus, God tells Moses that “Thou canst not see my face: for there shall no man see me, and live.” (Ex. 33:20 KJV). The Ascension is the triumphant reversal of these words. For today, a man greater than Moses, a man greater than Enoch and greater than Elijah, but a man all the same, sees the Face of the Father. He has “ascended into Heaven, and sitteth on the right hand of God, the Father Almighty.” Godhead wraps Himself in human nature, and humanity is plunged into the abyss of everlasting Light. A human being stands at the threshold of eternity. The Ascension brings humanity into the very Holy of Holies of the cosmos. We truly participate in this Ascension if we unite ourselves to Christ through the grace given us, especially the grace of the sacraments. If we one day enjoy the Blessed Vision of the Divine Essence, it will be through the eyes of our High Priest, our Head, the Lamb who is the Lamp of the New Jerusalem (Rev. 21:23). John Donne puts it thus:

Behold the Highest, parting hence away,

John Donne, “Ascension”

Lightens the dark clouds, which He treads upon;

Nor doth he by ascending show alone,

But first He, and He first enters the way.

By grace, we shall follow these luminous steps, someday. So many saints have – including today’s great saint, Philip Neri, Apostle of Rome. Their stories remind us that now is the time of faith, and hope, and the charity that breathes life into both.

If the Ascension is a lesson in Faith, it is just as much a lesson in Hope. It shows us which way we must go. It tells us that we must look to the hills, from whence cometh our help (Ps. 121:1). We need go neither backwards nor forwards, neither to the East nor to the West—but rather, up. Up, into the hidden mystery of the Divine Life. Our help is not from man but from the God-Man, the one who brought our very nature beyond the veil of the celestial temple. And what do the Apostles do? They imitate their Head and repair to the visible and earthly temple, there to sing and praise and preach the Gospel of the Lord. So have all the saints throughout the long, dark centuries since the Ascension. And so should we.

But even as we tabernacle in the visible Church, we are truly cloistered in the heart of the Most High. As St. Paul writes to the Colossians,

If ye then be risen with Christ, seek those things which are above, where Christ sitteth on the right hand of God. Set your affection on things above, not on things on the earth. For ye are dead, and your life is hid with Christ in God.

Colossians 3:1-3

Let us pray with the Apostles that we might one day ascend with Christ. And let us ever hold in remembrance that Jesus Christ is our High Priest, and He will always see us through.