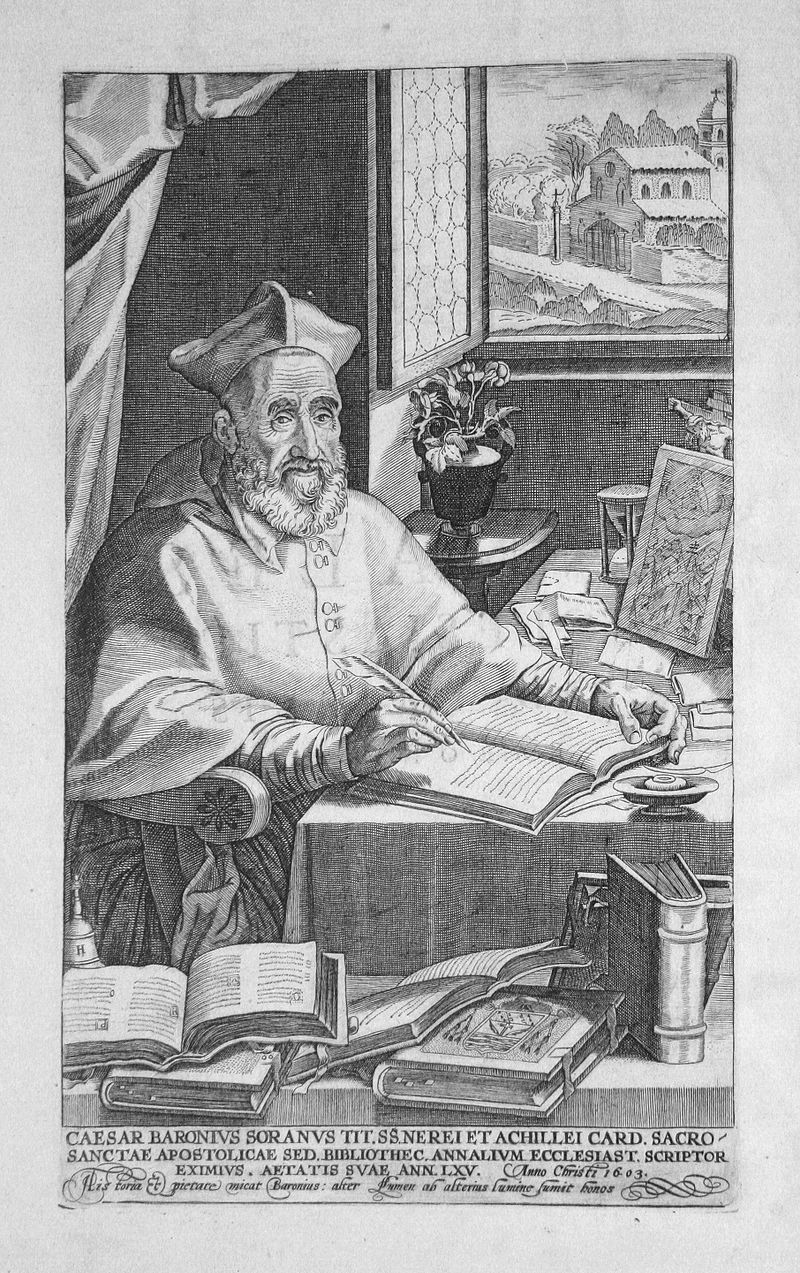

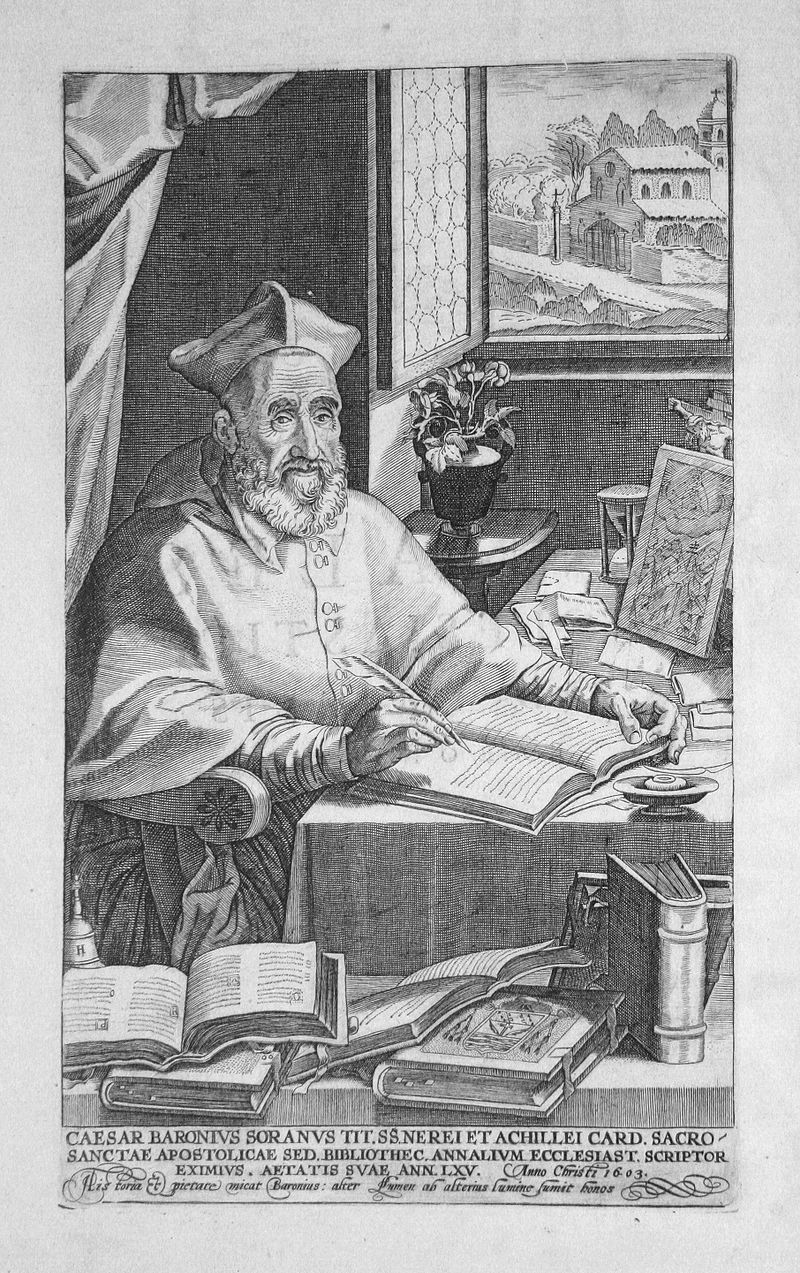

The Venerable Cardinal himself. This portrait is one of the few where his Cardinalatial arms can be glimpsed, on the cover of a book in the foreground. (Source).

Readers of this blog will learn with no surprise that, having finished Lady Amabel Kerr’s biography of the Venerable Cardinal Baronius, my admiration for this great Oratorian has increased tenfold. As I have concluded the volume, so lovingly edited and reprinted by Mediatrix Press, on the very birthday of the illustrious historian, I thought I might reproduce here two extended passages from Baronius’s correspondence that I found particularly edifying.

The first passage is taken from a letter that Baronius wrote to one Justin Calvin. I have thus far been unable to locate much further information about said Calvin, unrelated, I think, to the heresiarch Reformer. Baronius’s Annales and extended correspondence with Justin led to the latter’s eventual conversion. Calvin (or Justus Baronius Calvinus, as he was called once he added Baronius’s name to his own) went on to become a priest and author of, among other works, an Apologia that justified his conversion. God manifestly works in mysterious ways within the long lives of religious orders. He is inordinately fond of strange and unintended coincidences.

Baronius writes to the young convert:

I return many thanks to the great and most high God, whose tender mercies, as sings David, are over all His works, for having called you out of darkness into His marvellous light. No benefit, no grace can be greater than this, so see that you cherish it carefully and guard it jealously. Do not indulge in paeans of victory; but rather remember that exhortation of the Apostle to walk circumspectly, not as unwise but as wise, redeeming the time because the days are evil…When the devil has been overthrown, he is apt to rise up with renewed vigour, and assault his former conqueror more violently than ever. Our Lord tells us of the wicked spirit who, having gone out of a man, did not rest, but fetched seven other spirits more wicked than himself, and retook by fraud the soul whence he had been driven…Be sure that he will seek you who have escaped him and are now fighting in the ranks of the Church. He may not betray his designs, for he fears lest Saul-converted into Paul by his reconciliation to the Church-should by the first of divine love deal destruction on the lies by which he is wont to overcome men. You, a soldier of Jesus Christ, beware, and lose not hold on the shield of faith which you have taken up. Be master of yourself, overcome yourself, and take heed that you, who were once in the employ of the prince of darkness, be not ashamed of being enrolled under the banner of Christ your Captain…You have, however, no real cause for fear, but only for joy. Rejoice if you are found worthy to suffer anything for the Catholic faith and in defence of the truth. I showed your letter to our Supreme Pastor, who rejoiced to hear the bleating of his one-time lost sheep, who has been found worthy to hear the voice of the Shepherd. He is addressing to you an Apostolic letter, by which he embraces you as if with extended arms, and by his written words places you on his shoulders rejoicing. In him you will always find a true pastor and father. (Kerr 295-96).

There is much rich advice here for any convert. Baronius also displayed his perennial wisdom when he replied to a number of fellow Cardinals who censured the liberty with which he defended the independence of the Church against the claims of various princes and potentates—above all, the King of Spain. His response is inspiring for anyone who hopes to engage in the life of the mind. We read:

It behoves me to imitate our Lord and Master Jesus Christ, of whom the Gospel says that He taught as one having authority and not as the scribes, which means that He preached with truth and liberty, whereas they, in their adulation of Herod, yielded to that king’s taste in everything. Far be it from me, I repeat, to write like the scribes, and not declare the truth freely as did Christ. After Him I turn to the holy fathers of the Church, whose example, in writing, it behoves me to follow. In their maintenance of the truth in the face of those who attacked it, they displayed unbending constancy of soul. They did not make use of cringing, diluted, soft expressions, but, on the contrary, employed a language both grand and strong, mingling with it a sharpness of censure which converted their sentences into so many flashes of lightning. If you look through the Annals you will find scarcely a year in which some such example is not cited.

By studying the fathers and relating their acts I have by habit adopted their manner of speaking, which should not, in my opinion, be despised, for such speech is bestowed as a gift of the Spirit rather than obtained by human learning. When dealing with heretic or schismatic innovators, or else with princes who corrupt ecclesiastical discipline by their violation of the laws of the Church, or endeavour by their tyranny to reduce her to servitude, I have acquired the habit of writing with the indiscretion which you censure. The words of the prophet, “Cry, cease not, lift up thy voice like a trumpet, and show my people their wicked doings,” keep resounding in my ears as if from heaven. When Eugenius IV was made Pope, St. Bernard exhorted him to nominate Cardinals who should act as John did towards Herod, Moses towards the Egyptians, Phineas towards the fornicators, Elias towards the idolaters, Eliseus towards misers, Peter towards liars, Paul towards blasphemers, and, finally, as our Lord Himself acted towards traffickers in the temple. In other words he urged the Pope to choose men armed with zeal against sinners, who should act everywhere and in every way in such a manner as to sweep away the workers of iniquity. Such is the model drawn for us by the Holy Ghost, and if we do not conform ourselves to it we shall be convicted of deformity. (Kerr 318-20).

These are just some of the words which the Venerable Cardinal let slip as so much nectar from his pen and tongue. He was truly one of the greatest scholars that the Church has ever produced, and he revolutionized the discipline of ecclesiastical history. Yet Baronius always saw the Annales as a secondary work to the simple task of salvation. His humility was legendary, and Kerr’s portrait of Baronius captures this peculiar virtue in all its many expressions.

Fénelon writes somewhere that we are all saved with our disposition. And Baronius’s scholarly predilections color his devotional life. Kerr tells us of one of his favorite prayers in a brief but vivid scene:

It may be said that he never wasted a moment of that rare though precious time when it was permitted him to turn his thoughts directly to God. While driving about in his coach he used to pull down the blinds and give himself over unrestrainedly to the things of the soul, bidding his companion recall him to himself if anything occurred which required his attention. When thus shut into darkness he usually repeated the Holy Name over and over again, or else dwelt lovingly on his favourite interjection, “Eternitas, eternitas,” words which were but the epitome of his ceaseless longing for death and the state beyond the grave. (Kerr 282).

Baronius teaches us to use time—that is, our place in history—well. May we follow in his glorious footsteps and one day enjoy with him the eternity he so ardently desired.