Popular Catholic memory of Port-Royal, especially outside the Francophone world, is of a knot of disgruntled nuns who, in a spirit of disobedience to their lawful superior, refused to condemn the heresies of Cornelius Jansen. There are many problems with this unfair caricature, an inheritance of the final Ultramontane and Jesuit victory over Jansenism in the wake of the French Revolution. The truth is much more complicated, as truth tends to be. We too often forget that these nuns and the community of hermits, servants, and local peasants around them led a life of penance and prayer that was widely admired in their own time (even by saints, as Ellen Weaver notes, building on Louis Cognet and Augustin Gazier). The liturgical and devotional aspects of Port-Royal’s community life have too often been neglected by scholars and, especially, popular Catholic writers who turn their eyes to the Jansenists. We have fixated too much on the controversies of the 1640s-60s, and too little on what daily life was like for those who worked out their salvation in “fear and trembling” at Port-Royal.

It is thus with great pleasure that I here co-publish an edifying and informative excerpt from the Voyages liturgiques of Jean-Baptiste Le Brun des Marettes, Sieur de Moléon, translated by the authors at Canticum Salomonis. They have already given an excellent overview of this text, in which they note that Marettes, educated at the Petites écoles de Port-Royal, retained something of a Jansenist liturgical sensibility. They sum up his work thus:

On the whole, the picture he paints is of a French people who are deeply engaged in their liturgical life and cathedral chapters that observe the whole office. His “taste” is for antiquity and ceremonial splendor, and this leads him to admire the pontifical liturgies of the middle ages. Admittedly, perhaps he does so because he believes them to be much more ancient than the extant source-books: expressions of the most ancient Gallic liturgies.

Aelredus Rievallensis, “The Voyages Liturgiques: A Roundup,” Canticum Salomonis

Their introduction to the translated chapter on Port-Royal, pages 234-43, follows with the text below. However, let me add a brief preface of my own.

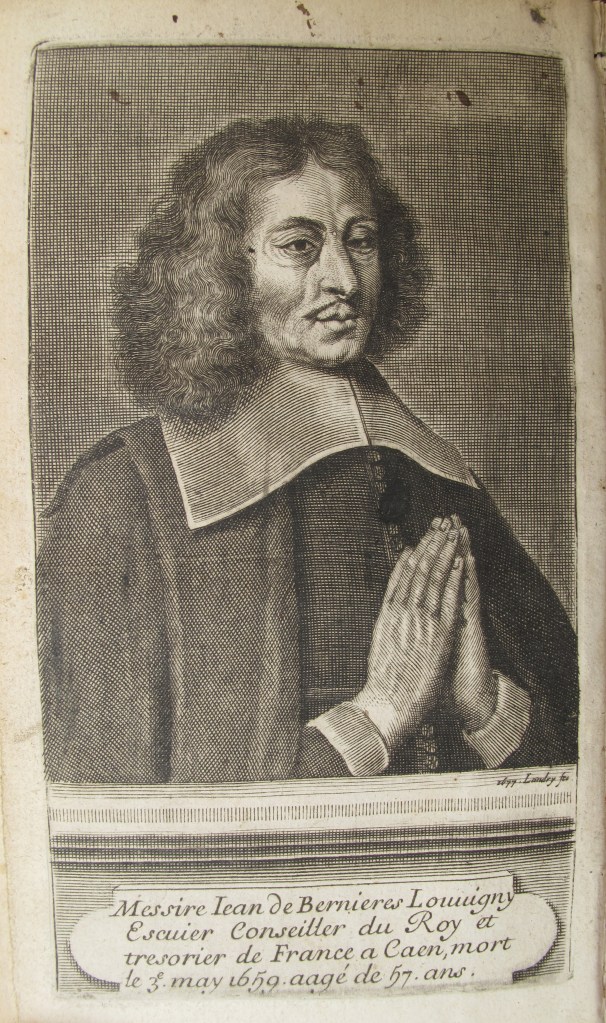

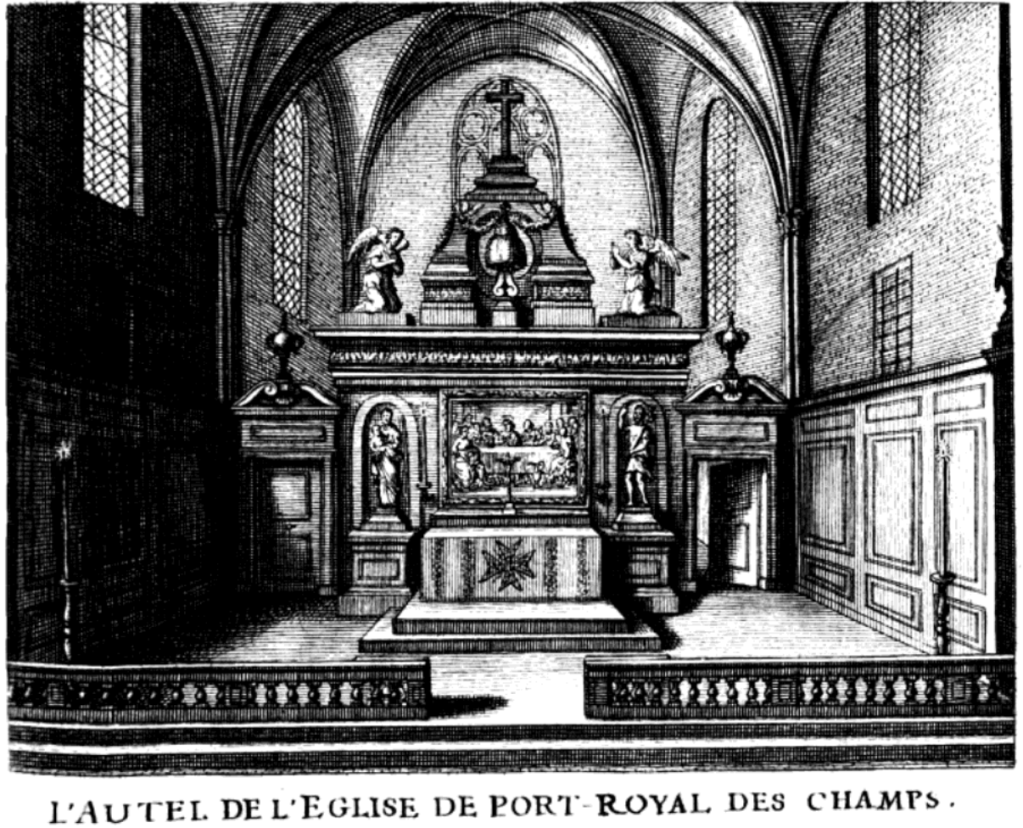

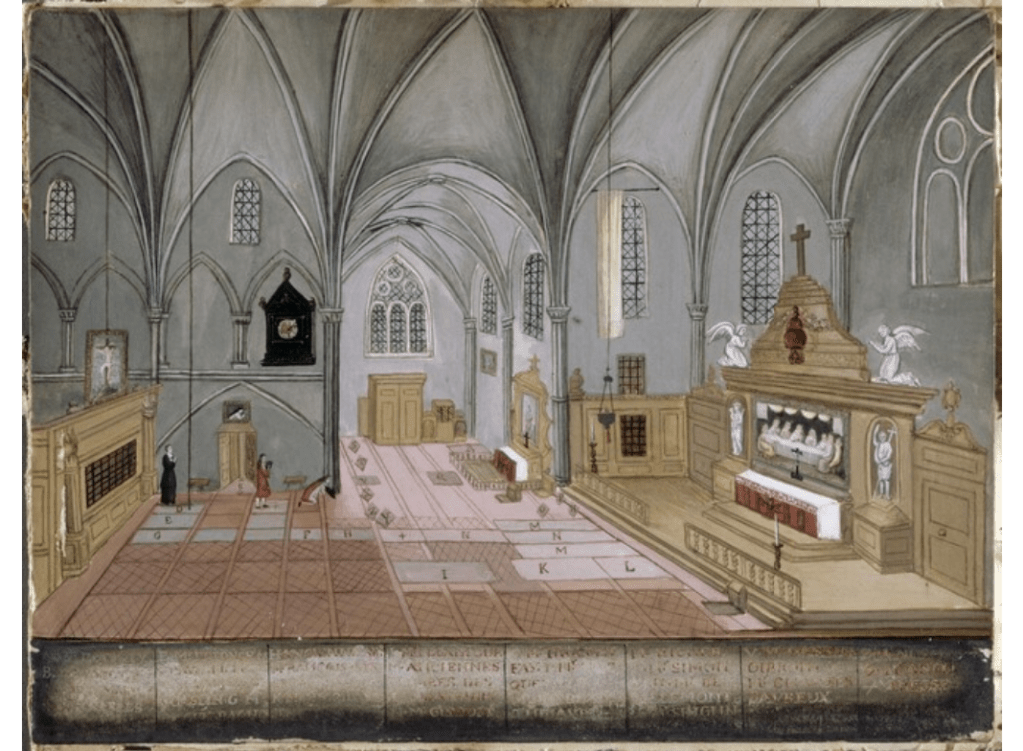

The Voyages liturgiques offers several fascinating glimpses into the communal piety of Port-Royal des Champs. Marettes pays attention to the physical space of Port-Royal. He reports that the paintings in the church are by Philippe de Champaigne. The great French classicist had a daughter at the convent, Soeur Catherine de Saint-Suzanne, and seems to have provided the monastery with several portraits of both nuns and solitaires as well as several edifying works of art. The large altarpiece depicting the Last Supper is today in the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon, with a copy in the Louvre. Marettes devotes particular attention to the epitaphs in and around the church. The epitaphs for the solitaires Emmanuel le Cerf, an Oratorian, and Jean Hamon, a medical doctor and mystic, are especially moving.

Yet it is the liturgical and communal details he provides here that are most exciting for the historian of Jansenism and which, in fact, force us to take the nuns more seriously as daughters of St. Benedict and St. Bernard. Following the egalitarian reform of Mère Angélique, the Abbey did not require dowries of its postulants. Singing the office according to the use of Paris, they prayed the whole Psalter every week. The first chapter of the Constitutions of Port-Royal is dedicated to veneration of the Blessed Sacrament, a significant organizational choice. There were in fact both communal and individual devotions to the Blessed Sacrament at Port-Royal; for, “in addition to engaging in perpetual adoration…they also have the custom of prostrating themselves before the Sacrament before going up to receive holy communion.” Following an ancient usage, they only exposed the Blessed Sacrament during the Octave of Corpus Christi, and even then, only after the daily High Mass. Usually, the Sacrament was reserved in a hanging pyx, “attached to the end of a veiled wooden fixture shaped like a crosier.” The French Jansenists seem to have had a fixation with hanging pyxes; both M. Saint-Cyran and M. Singlin wrote about “suspension” of the Blessed Sacrament in this form.

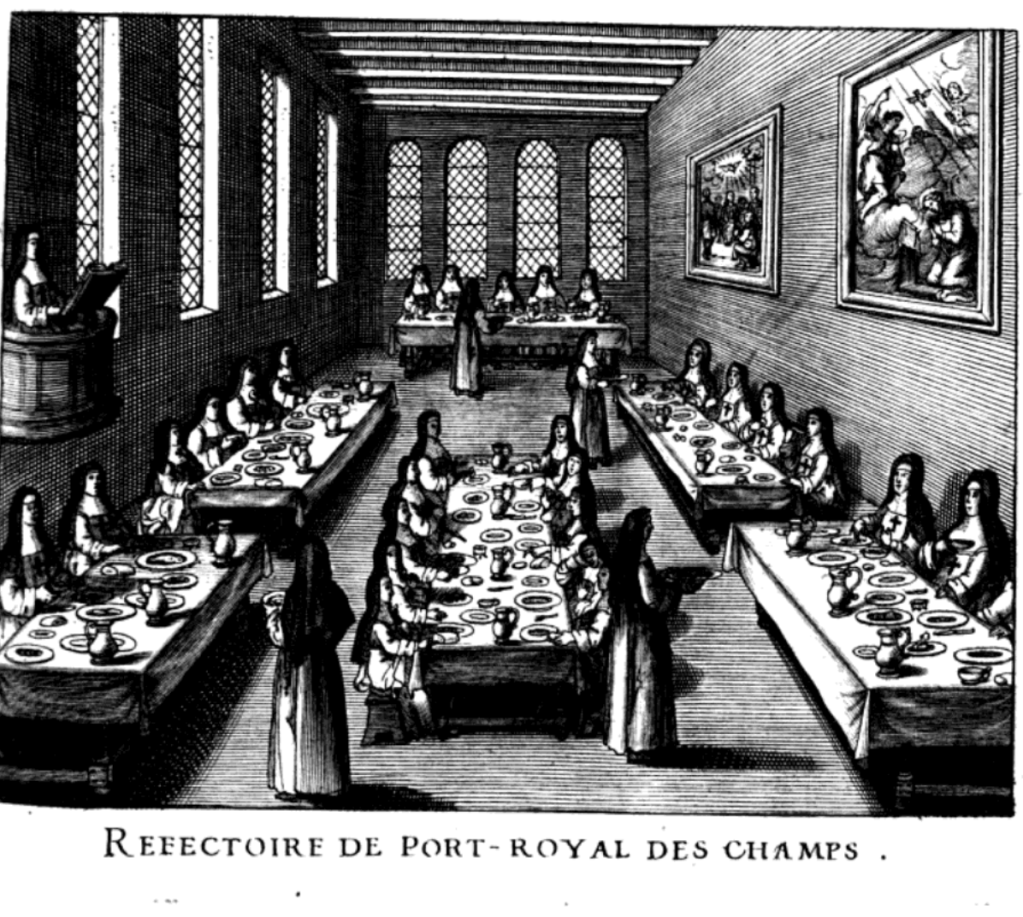

The community would meet for chapter daily. The nuns engaged in an exacting and penitential adherence to the Rule, including silence, vegetarianism, abstinence from strong drink, and only a single meal per day in Lent. In their persons as in their ecclesiastical furniture, they followed the Cistercian spirit of holy simplicity; Marettes reports that “The nuns’ habits are coarse, and there is neither gold nor silver in their church vestments.” Yet they were not without the consolation of quiet reading in the garden during summertime.

Marettes reminds us that Port-Royal was not just a community of nuns, but also included male hermits and domestics. He writes, “After the Credo, the priest descends to the bottom of the altar steps and blesses the bread offered by one of the abbey’s domestics.” These servants and workers seem to have had a special participation in the liturgy through this rite, so reminiscent of the blessing of bread found even today in the Eastern Churches. The Necrology of Port-Royal includes these men as well in its roll-call of the Abbey’s luminaries, confirming the sometimes-overlooked egalitarianism of Port-Royaliste spirituality.

One of the more striking moments in the text comes when Marettes writes that “On Sundays and feasts of abstention from servile work there is a general communion; at every Mass said in this church at least one of the nuns receives communion.” The practice of lay communion at every Mass contradicts the usual picture of the Jansenists receiving infrequently or as discouraging lay communion. The nuns themselves, at least, seem to have received the Sacrament daily.

And I cannot help but see in one custom a potent metaphor for the troubled history of the monastery. Marettes writes, “On Holy Saturday, they extinguish the lights throughout the entire house, and during the Office they bring back the newly blessed fire.” The extraordinary and unjust persecution that the nuns endured under the authorities of the French Church and State – to the point of being deprived of communion during Easter, of being denied the last rites, of condemnation to a slow decline even after reconciliation with the Archbishop, and, at the very end, of having their bodies desecrated and even fed to the dogs – must have seemed like a very long Holy Saturday. Yet the blessed fire of the Holy Ghost does not abandon those who faithfully serve God in humble prayer and penitence. Where we find the Cross, Resurrection follows.

It is not for us to resurrect the nuns and solitaires of Port-Royal; historians can only do so much. But by taking the dead on their own terms, we can at least pay them the homage we owe any historical figure, and perhaps especially the defeated, the maligned, the powerless, and the forgotten. Only by doing so can we reckon with our implication in the longstanding myths that efface those voices. It is my hope that the publication of this important translation will help us in that process of revision.

In his monumental Institutions liturgiques, Dom Prosper Guéranger famously castigated the Neo-Gallican liturgies that proliferated in 17th and 18th century France for, inter alia, being products of Jansenist inspiration. Setting aside the question of whether these liturgies betray a heretical notion of predestination, it is true that many figures associated with the Jansenist movement did have a keen interest in the liturgy. Contrary to what one might expect given Dom Guéranger’s accusations, these “Jansenists” prized respect for ancient custom and repudiated needless novelty.

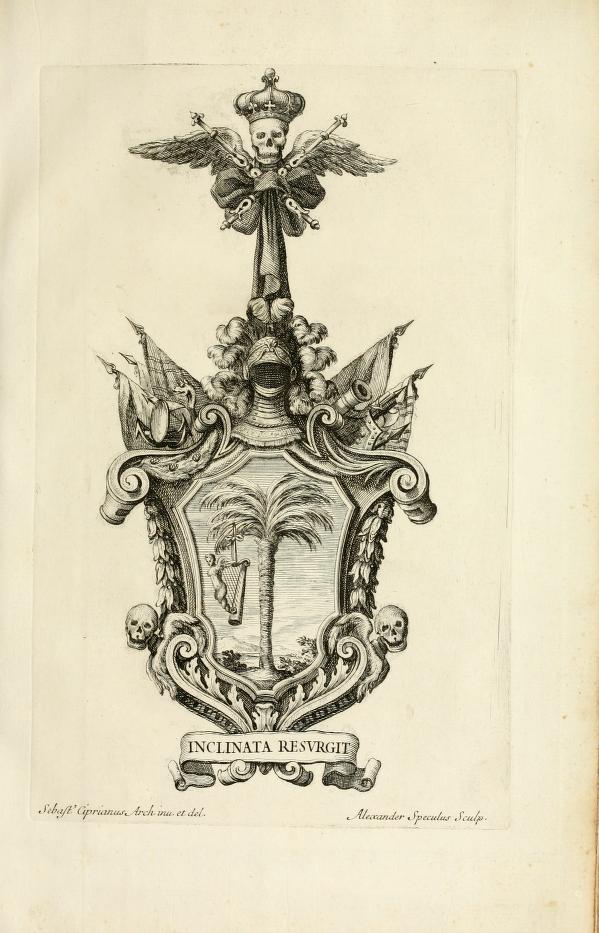

The intellectual centre of Jansenism was the Abbey of Port-Royal, a community of Cistercian nuns who were reformed in the early 17th century by the formidable Abbess Angélique Arnauld and became noted for their exemplary religious observance and cultivation of liturgical piety. This attracted a number of intellectuals who chose to settle as solitaires on the abbey grounds, leading a retired life of study and simple manual labour, including Angélique’s brother Antoine, one of the most prominent Jansenist theologians. Both the nuns and solitaries set up schools to teach neighbouring children.

One of those children was Jean-Baptiste Le Brun des Marettes, whom our readers will remember as the author of the Voyages liturgiques. His father had been sent to the galleys for publishing Jansenist works, and Jean-Baptiste himself once did a stint at the Bastille for his involvement in the controversy. His main interest, however, was not moral theology but liturgy. His Voyages evince his veneration for liturgical antiquity and opposition to modern developments in matters of ritual, furnishing, and vestments. Yet he found a way to reconcile such views with his enthusiasm for the Neo-Gallican reforms of the Mass and Office, ultimately sharing the hubristic certainty of most men of his age that their own putative enlightenment was able to improve upon “Gothic barbarism”. Our Aelredus has described and critiqued the seemingly contradictory tastes that Jean-Baptiste Le Brun shared with other Jansenist figures.

With these remarks in mind, let us see how the liturgy was celebrated in the Jansenist stronghold of Port-Royal, in a chapter of the Voyages that Jean-Baptiste Le Brun wrote before the abbey’s suppression in 1708 and the destruction of most of its buildings. (Although the Voyages was published in 1718, Le Brun employs the present tense in this chapter.)

We are obliged to the Amish Catholic for his help in translating this chapter.

Port-Royal-des-Champs is an abbey of nuns of the Order of Cîteaux lying between Versailles and the former monastery of Chevreuse.

The church is quite large, and its simplicity and cleanliness inspires respect and devotion.

The main altar is not attached to the wall, since the ample and well-kept sacristy is located behind it. Above the altar hangs the holy pyx, attached to the end of a veiled wooden fixture shaped like a crosier. It is set under a large crucifix above a well-regarded painting of the Last Supper by Philippe de Champaigne.

There is nothing on the altar but a crucifix. The four wooden candlesticks are set on the ground at its sides.

The woodwork of the sanctuary and parquet floor is very well maintained, as is that of the nuns’ choir. Indeed, the stalls are kept in such good condition that one would think they were carved not twenty years ago, when in fact they are over 150 years old.1

The church contains some paintings in the style of Champaigne, and a very well-kept holy water basin to the right of its entry.

Inside the cloister, there are several tombs of abbesses and other nuns. From these tombs one can garner

1. that the first abbesses of the Order of Cîteaux, following the spirit of St Bernard, did not have croziers. Even today, the Abbess of Port-Royal does not use one.

2. that in this monastery the nuns used to be consecrated by the bishop. Two of them are represented on the same tomb wearing a sort of maniple.2 See figure XIV. The inscription around the tomb reads:

“Here lie two blood-sisters, consecrated nuns of this abbey, Adeline and Nicole aux Pieds d’Estampes. May their souls rest in everlasting peace. Amen. Adeline died in the year of our Lord 1288.”3

There is an ancient necrology or obituary in this abbey that includes the ritual for the consecration or blessing of a nun. It describes how on these occasions the bishop celebrated Mass and gave communion to the nun he blessed. To this effect he consecrated a large host which he broke into eight particles, giving one as communion to the nun. He then placed the seven other particles of his host in her right hand, covered by a Dominical or small white cloth. During the eight days after her consecration or blessing, she gave herself these particles as communion. Priests also used to give themselves communion during the forty days after their ordination or consecration.4

Under the lamp by the baluster lies a tomb dated 1327, if I remember correctly, which is worthy of description, especially given that its most interesting aspect is misreported in the Gallia Christiana of the brothers de Sainte-Marthe.

It used to be the custom for devout noble ladies to take up the nun’s habit during their last illness, or at least to be clothed in it after their death. See, for example, the tomb of Queen Blanche, mother of King St Louis, at Maubuisson Abbey near Pontoise. Here in Port-Royal we find the tomb of one Dame Marguerite de Levi—wife of Matthew V de Marly of the illustrious House of Montmorency, Grand-Chamberlain of France—buried in a nun’s habit, with this inscription:

“Here rested, whose name thou shalt have there hereafter. Marguerite was the wife of Matthew de Marly, and daughter of the noble Guy de Levi. She bore six boys. After her husband died, she went to the nuns. Amongst the claustral sisters she chose to make her home. In her long rest, may she be buried in nun’s clothing. May eternal light shine upon her in peace everlasting. Year 1327.”5

By the door of the church, in the vestibule, is the tomb of a priest vested in his vestments. His chasuble is rounded in all corners, not cut or clipped, gathered up over his arms, and hanging down below and behind him in points. His maniple is not wider below than it is on top, and he does not wear his stole crossed over his breast, but straight down like bishops, Carthusians, and the ancient monks of Cluny, who have rejected innovation on this point. His alb has apparels on the bottom matching the vestments: this is what the manuscripts call the alba parata. They are still used in cathedral churches and ancient abbeys.

Next to the church door and the clock tower lies the small cemetery of domestics, where two epitaphs are worthy of note.

“To God the Best and Greatest.

“Here lies Emmanuel le Cerf, who, after dedicating most of his life to the education of the people, deemed the evangelical life superior to evangelical preaching and, in order that he who had lived only for others should die to himself, embraced a penitential life in his old age as eagerly as he did seriously. He embraced the weight of old age, more conducive to suffering than aught else, and various diseases of the body as remedy for his soul and advantageous provision for the journey to eternity. Humbly he awaited death in this port of rest, living no longer as a priest but as a layman, and attained it nearly ninety years old. He died on 8 December 1674, and wished to be buried in this cemetery near the Cross. May he rest in peace.”6

And the other:

“Here rests Jean Hamon, doctor, who, having spent his youth in the study of letters, was eminently learned in the Greek and Latin tongues. Seeing that he flourished in the University of Paris by the renown of his eloquence, and that his fame grew daily for his skill of medicine, he feared the lure of flattery and fame and the haughtiness of life. Suddenly stirred by the prompting of the Holy Spirit, he quickly poured out the value of his inheritance into the bosom of the poor and, in the thirty-third year of his age, he dragged himself into this solitude, as he had long pondered doing. First he applied himself to the labour of the fields, then to serving the ministers of Christ, and soon returned to his original profession, healing the wounded members of the Redeemer in the person of the poor, among whom he honoured the handmaidens of Christ as the spouses of the Lord. He wore the coarsest garments, fasting nearly every day, slept on a board, spent day and night in nearly perpetual vigils, prayer, and meditation, nocturnal works everywhere breathing the love of God. For thirty-seven years he accumulated the toils of medicine, walking some twelve leagues every day, very often while fasting, to visit the sick in the villages, providing them what they might need, helping them by counsel, by hand, with medicines, with food whereof he deprived himself, living for twenty-two years on eating bran bread and water, which he ate secretly and alone, while standing up. As wisely as he had lived, considering every day his last, thus he departed this life in the Lord, amidst the prayers and tears of his brethren, in deep silence and sweet meditation of the Lord’s mercies, with his eyes, mind, and heart fixed on Jesus Christ, mediator between God and man, rejoicing that he obtained the tranquil death for which he had prayed, that he might gain eternal life, at the age of 69, on 22 February 1687.”7

Heeding the spirit of St Bernard, the nuns are subject to the Lord Archbishop of Paris, who is their superior. They also sing the office according to the use of Paris, except that they sing the ferial psalms every day in order to fulfill the Rule of St Benedict which they follow, and which binds them to saying the entire psalter every week. This they do with the approbation of the late M. de Harlay, Archbishop of Paris.

At the blessing and aspersion of holy water on Sundays, the abbess and her nuns come forward to receive it at the grill from the priest’s hand.

After the Credo, the priest descends to the bottom of the altar steps and blesses the bread offered by one of the abbey’s domestics. He then announces any feasts or fasting days during the coming week, and gives a short exhortation or explanation of the day’s Gospel.

At every High Mass of the year, the sacristan or thurifer goes to the nuns’ grill at the end of the Credo to receive, through a hatch in the screen, a box from the sister sacristan containing the exact number of hosts needed for the sisters who are to receive communion. He brings them to the altar and gives them the celebrant.

At High Masses for the Dead, the sacristan goes to the grill to receive the bread, a large host, and the wine in a cruet, and brings them to the altar. He gives the host to the priest on the paten, kissing it on the inside edge, and the cruet of wine to the deacon, who pours the wine into the chalice.

At the Agnus Dei, the nuns embrace and give each other the kiss of peace.

On Sundays and feasts of abstention from servile work there is a general communion; at every Mass said in this church at least one of the nuns receives communion.

Devotion for the most blessed Sacrament is so great in this monastery that in addition to engaging in perpetual adoration as part of the Institute of the Blessed Sacrament (it is for this reason that they have exchanged their black scapular for a white one charged with a scarlet cross over the breast, about two fingers in width and a half-foot tall), they also have the custom of prostrating themselves before the Sacrament before going up to receive holy communion.

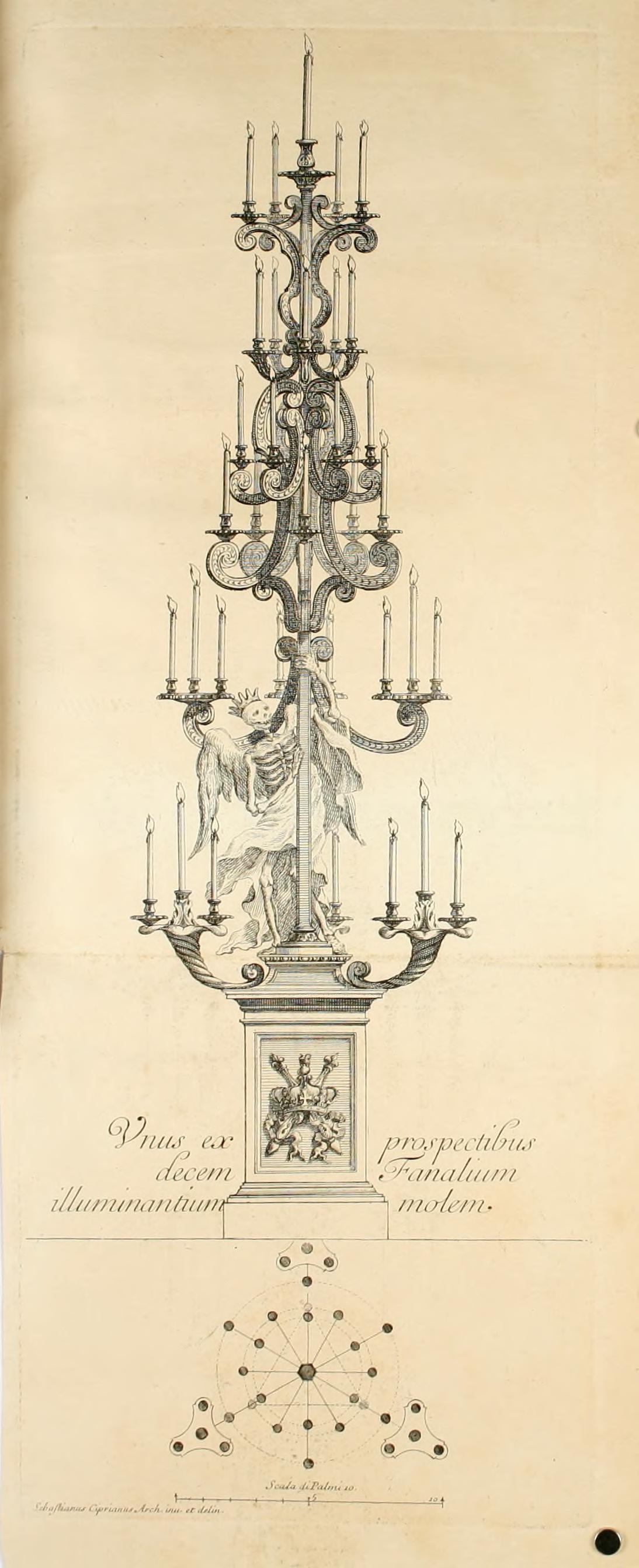

Nevertheless, the Blessed Sacrament is only exposed during the Octave of Corpus Christi, and this every day after High Mass. For here Mass is never said at an altar where the Blessed Sacrament is exposed. We will come back to this point.

The nuns of this monastery observe an exact and rigorous silence. Except in cases of illness, they never eat meat, and fish only rarely, about twelve or fifteen times a year. They solely drink water, and observe the great fast of Lent in its full rigour, as in the age of St Bernard, eating only at five in the evening after Vespers, which they usually say at 4 p.m., even though they wake up at night to sing Matins and perform manual labour during the day.

A spiritual conference is held after lunch, during which they continue to work, and during which it is not permitted to speak aloud.

During the summer, the nuns are sometimes allowed to go into the garden after dinner, but many refrain from doing so, and those that go do so separately, taking a book to read or some work to do.

Matins are said here at 2 a.m. together with Lauds, but in winter Lauds are said separately at 6 a.m, and then a Low Mass is celebrated between Lauds and Prime. During the rest of the year, Prime is said at 6 a.m., followed by a Conventual Low Mass. Chapter follows with a reading from the Martyrology, the Necrology, and the Rule, some chapter of which the Abbess explicates once or twice a week. Then they hold the proclamation of faults, and appropriate penances are imposed.

Terce is said at 8:30 a.m., followed by High Mass. Sext is at 11 a.m., and on ecclesiastical fast days at 11:45, after which they go to lunch, except in Lent when they do not dine, for in the Rule of St Benedict to lunch means not to fast. None is at 2 p.m. in winter and at 2:30 in summer.

The first bell for Vespers rings at 4 p.m., and the office begins some fifteen minutes later. It finishes at 5 or 5:15, for they sing very unhurriedly and distinctly. After Vespers in Lent, they sound the refectory bell, and the nuns go there to lunch and dine together. One sees nuns following this regime until they are 72 or 75 or even older. Not too long ago there was a priest who, in Lent, only ate in the evening, even though he was 87 years old, and lived till he was 92.

On Holy Saturday, they extinguish the lights throughout the entire house, and during the Office they bring back the newly blessed fire.

The nuns’ habits are coarse, and there is neither gold nor silver in their church vestments.

The Abbey receives girls without a dowry, and makes neither pacts or conventions for the reception of nuns, following the primitive spirit of their monastery, as is clear from the following acts:

“Be it known to all men that I, Eudes de Thiverval, esquire, and Thècle my wife gave in pure and perpetual alms, for the salvation of our souls and those of our ancestors, two bushels of corn, that is, one of winter-crop and the other of oats from our tithe-district of Jouy, to the Church of Our Lady of Port-Royal and the nuns serving God therein, to be collected every day on the feast of St Remigius. Be it known that the Abbess and Convent of the said place freely received one of our daughters into their society of nuns. Not wishing to incur the vice of ingratitude, we have given the said two bushels of corn in alms to the said House of our will without any pact. Which, that it may remain ratified and fixed, we have made to be confirmed by the support of our seal. Done in the year of grace 1216.”8

Another:

“Renaud, by the grace of God bishop of Chartres, to all who would earlier or later inspect the present page, in the Lord greeting. We make it known to all future and present that by these presents that the Abbess and Convent of Nuns of Porrois [i.e. Port-Royal] freely received in charity Asceline, daughter of Hugues de Marchais, esquire, as a sister and nun of God. Thereafter the said esquire, lest he should give away his said daughter to be betrothed to Christ without a dowry from part of his patrimony, standing in our presence did give and grant to the Church of Porrois and the nuns serving God therein in perpetual alms for the portion of his said daughter the return of one annual bushel of corn in his grange of Marchais or Lonville to be collected every year in the Paris measure of Dourdan, and three firkins of wine in his vineyard of Marchais to be collected yearly, and ten shillings in his census-district of Marchais. That his gift may remain ratified and fixed, at the petition of the same Hugues we have made the present letters to be confirmed by our seal in testimony. Done at Chartres in the year of the Incarnation of Our Lord 1217, in the month of April.”9

Another:

“Be it known to all them that I, Odeline de Sèvre, gave in pure and perpetual alms to the house of Port-Royal for the soul of my late husband Enguerrand of happy memory, and for the salvation of my soul, and of all my children and ancestors, and especially for the salvation and love of my daughter Marguerite who received the religious habit in the same house, four arpents of vine in my clos of Sèvre to be possessed in perpetuity. My sons Gervais the eldest, Roger, and Simon praised, willed, and granted this donation, to whom it belonged by hereditary right. And further we offered the same donation with the book upon the altar of Port-Royal. In testimony and perpetual confirmation whereof, since by said sons Gervais, Roger, and Simon were not yet esquires and did not yet have seals, I the said Odeline confirmed the present charter by the support of my seal with their will and convent. Done on the year of our Lord 1228.”10

- Author’s note: [After the Abbey’s suppression] the altar and choir stalls were purchased by the Cistercian nuns of Paris and placed in their church, where one can see them.

- Translators’ note: As did Carthusian nuns.

- Hic jacent duae sorores germanae, hujus praesentis Abbatiae Moniales Deo sacratae, Adelina et Nicholaa dictae ad Pedem, de Stampis quondam progenitae: quarum animae in pace perpetua requiescant. Amen. Obiit dicta Adelina anno Domini M. C. C. octog. octavo.

- Author’s note: See Fulbert. Epist. 2 ad Finard. Rituale Rotomag. ann. 1651.

- Hic requievit, ibi post cujus nomen habebis.

Margareta fuit Matthæi Malliancensis

Uxor; & hanc genuit generosus Guido Levensis.

Sex parit ista mares. Vir obit. Petit hæc Moniales.

Intra claustrales elegit esse lares.

In requie multa sit Nonnæ veste sepulta;

Luceat æterna sibi lux in pace suprema.

Anno M. C. bis, LX. bis, V. semel, I. bis. - D. O. M.

Hic jacet Emmanuel le Cerf, qui cum majorem vitæ partem erudiendis populis consumpsisset, vitam evangelicam evanglicæ prædicationi anteponendam ratus, ut sibi moreretur, qui aliis tantum vixerat, ad pœnitentiam accurrit senex eo festinantius, quo serius; pondusque ipsum senectutis, quo nihil ad patiendum aptius, et varios corporis morbos in remedium animæ conversos, tanquam opportunum æternitatis viaticum amplexus; mortem humilis, nec se jam sacerdotem, sed laicum gerens, in hoc quietis portu expectavit, quæ obtigit fere nonagenario. Obiit 8 Decembris 1674 et in Cœmeterio prope Crucem sepeliri voluit. Requiescat in pace. - Hic quiescit Joannes Hamon Medicus, qui adolescentia in studiis litterarum transacta, latine græceque egregie doctus, cum in Academia Parisiensi eloquentiæ laude floreret, et medendi peritia in dies inclaresceret, famae blandientis insidias et superbiam vitæ metuens, Spiritus impetu subito percitus, patrimonii pretio in sinum pauperum festinanter effuso, anno ætatis xxxiij in solitudinem hanc, quam diu jam meditabatur, se proripuit. Ubi primum opere rustico exercitus, tum Christi ministris famulatus, mox professioni pristinæ redditus, membra Redemptoris infirma curans in pauperibus, inter quos ancillas Christi quasi sponsas Domini sui suspexit; veste vilissima, jejuniis prope quotidianis, cubatione in asseribus, pervigiliis, precatione, et meditatione diu noctuque fere perpetua, lucubrationibus amorem Dei undique spirantibus, cumulavit ærumnas medendi quas toleravit per annos xxxvj quotidiano pedestri xij plus minus milliarum itinere, quod sæpissime jejunus conficiebat, villarum obiens ægros, eorumque commodis serviens consilio, manu, medicamentis, alimentis, quibus se defraudabat, pane furfureo et aqua, idque clam et solus, et stando per annos xxij. sustentans vitam, quam ut sapienter duxerat, quasi quotidie moriturus, ita inter fratrum preces et lacrymas in alto silentio, misericordias Domini suavissime recolens; atque in Mediatorem Dei et hominum Jesum Christum, oculis, mente, t corde defixus, exitu ad votum suum tranquillo lætus, ut æternum victurus clausit in Domino, annos natus 69 dies 20 viij Kalend. Mart. anni 1687.

- Noverint universi quod ego Odo de Tiverval miles et Thecla uxor mea dedimus in puram et perpetuam eleemosynam, pro remedio animarum nostrarum et antecessorum nostrorum, Ecclesiae beatae Mariae de Portu-Regio et Monialibus ibidem Deo servientibus duos modios bladi, unum scilicet hibernagii, et alterum avenae in decima nostra de Joüy, singulis annis in festo S. Remigii percipiendos. Sciendum vero est quod Abbatissa et ejusdem loci Conventus unam de filiabus nostris in societatem Monialium benigne receperunt. Nos vero ingratudinis vitium incurrere nolentes, praedictos duos modios dictae jam domui de voluntate nostra sine aliquo pacto eleemosynavimus. Quod ut ratum et immobile perseveret, sigilli nostri munimine fecimus roborari. Actum anno gratiae M. CC. xvj.

- Reginaldus Dei gratia Cartonensis Episcopus, universis primis et posteris praesentem paginam inspecturis salutem in Domino. Notum facimus omnibus tam futuris quam praesentibus quod, quoniam Abbatissa et Conventus Sanctimonialium de Porregio Acelinam filiam Hugonis de Marchesio militis in sororem et sanctimonialiem Dei et caritatis intuitu gratis receperant, postmodum dictus miles in nostra constitutus praesentia, ne dictam filiam suam nuptam Christi parte sui patrominii relinqueret indotatam, Ecclesiae de Porregio et Monialibus ibi Deo servientibus dedit et concessit in perpetuam eleemosynam, pro portione dictae filiae suae unum modium bladi annui redditus in granchia sua de Marchesio vel de Lonvilla singulis annis percipiendum ad mensuram Parisiensem de Dordano, et tres modios vini in vinea sua de Marchesio annuatim percipiendos, et decem solidos in censu suo de Marchesio. Ut autem donum ejus ratum et stabile permaneret, ad petitionem ipsius Hugonis praesentes Litteras in testimonium sigillo nostro fecimus roborari. Actum Carnoti anno Dominicae Incarnationis M. CC. septimo decimo, mense Aprili.

- Noverint universi quod ego Odelina de Sèvre donavi in puram et perpetuam eleemosynam domui Portus-Regis pro anima bonae memoriae Ingeranni quondam mariti mei, et pro salute animae meae, et omnium liberorum et progenitorum meorum; et maxime pro salute et amore Margaretae filiae meae quae in eadem domo religionis habitum assumpserat, quatuor arpentos vineae in clauso meo de Sèvre jure perpetuo possidendos. Hanc autem donationem laudaverunt, voluerunt et concesserunt filii mei Gervasius primogenitus, Rogerus et Simon, ad quos eadem donatio jure hereditario pertinebat. Immo et ipsi eandem donationem obtulimus cum libro super altare Portus Regis. In cujus rei testimonium et conformationem perpetuam ego praedicta Odelina, quia praedicti filii mei G. R. et Simon necdum milites erant, et necdum sigilla habebant, de voluntate eorum et assensu praesentem Chartam sigilli mei munimine roboravi. Actum anno Domini M. CC. vigesimo octavo.