The 18th century was a Golden Age of clerical satire – and clerical eccentricity – in England. (Source)

What a day of loons it has been. After discovering the narrative of that wandering bishop which I brought to my readers’ attention earlier this afternoon, I have since come across two wonderful articles about the venerable tradition of eccentricity in the Church of England. The first is over at the Church Times. The Rev. Fergus Butler-Gallie, a curate in Liverpool, has written a book entitled A Field Guide to the English Clergy (One World Press, 2018). In his article at the CT, Butler-Gallie provides a taste of what is assuredly a very fun book indeed. Take just one of the bizarre figures he profiles:

William Buckland, a Victorian Dean of Westminster, became obsessed with eating as many animals as possible, from porpoise and panther to mole fricassee and mice on toast, even managing to gobble up the mummified heart of King Louis XIV while being shown round the Archbishop of York’s stately home.

He was no fool, though. The first person ever to excavate an entire dinosaur skeleton (although he was more interested in other prehistoric remains, writing on a desk made out of dinosaur faeces), he once disproved a supposed miracle in France by being able to prove (by taste, of course) that a supposed saint’s blood was, in fact, bat urine.

Or consider this parson:

The Revd Thomas Patten was a real-life Dr Syn, helping to run a smuggling operation on the north-Kent coast. Patten would preach interminably boring sermons until a parishioner held up a lemon, a sign that someone had agreed to buy his drinks for the evening at the tavern opposite, at which point he managed to terminate the service with astonishing alacrity (a ruse, I’m sure, no clergy reading this would even consider replicating).

If the rest of the book is as fascinating at these anecdotes suggest, it will be a classic in no time – right up there with Loose Canon and The Mitred Earl. Apparently it’s been getting rave reviews. (I’ll add that if any of you are looking for a Christmas gift for your favorite Catholic blogger, it’s going for under £10 at Amazon).

Today I also came across an article about one of Butler-Gallie’s subjects, the Rev. R.S. Hawker, also known as the “Mermaid of Morwenstow.” Alas, as I am not a subscriber to The Spectator, I cannot read it. Those who can are encouraged to do so.

One of my favorite clerical eccentrics whom I doubt that Butler-Gallie covers is the Rev. William Alexander Ayton, vicar of Chacombe in Oxfordshire. You can read more about him in my article, “On the Wings of the Dawn – the Lure of the Occult.”

Though of course there are few stories of clerical eccentricity as amusing as the infamous dinner related by Brian Fothergill in his life of Frederick Hervey, Bishop of Derry. Fothergill tells us that

On one occasion when a particularly rich living had fallen vacant he invited the fattest of his clergy and entertained them with a splendid dinner. As they rose heavily from the table he proposed that they should run a race and that the winner should have the living as his prize. Greed contending with consternation the fat clerics were sent panting and purple-faced on their way, but the Bishop had so planned it that the course took them across a stretch of boggy ground where they were all left floundering and gasping in the mud, quite incapable of continuing. None reached the winning-point. The living was bestowed elsewhere and the Bishop, though hardly his exhausted and humiliated guests, found the evening highly diverting. (The Mitred Earl, 27).

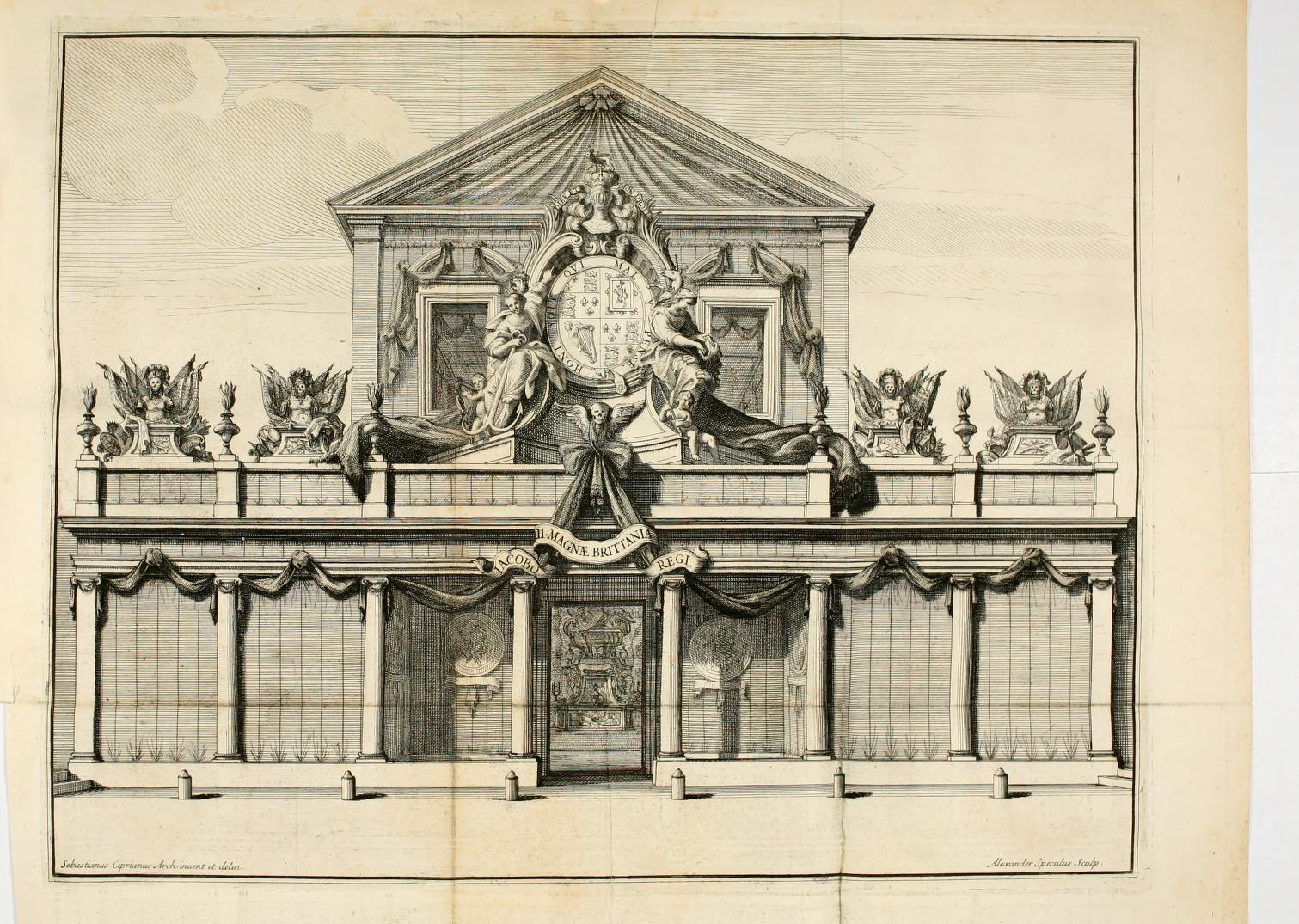

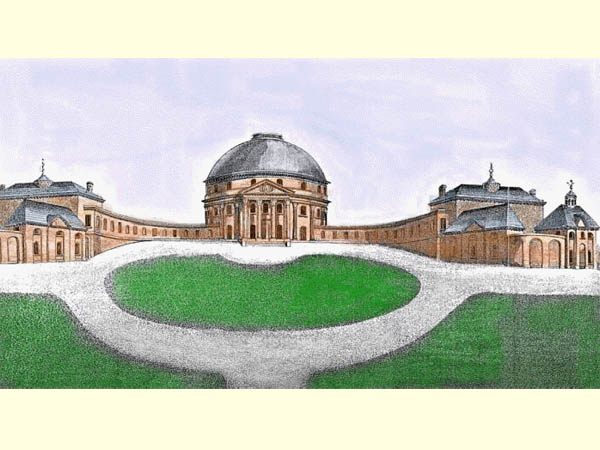

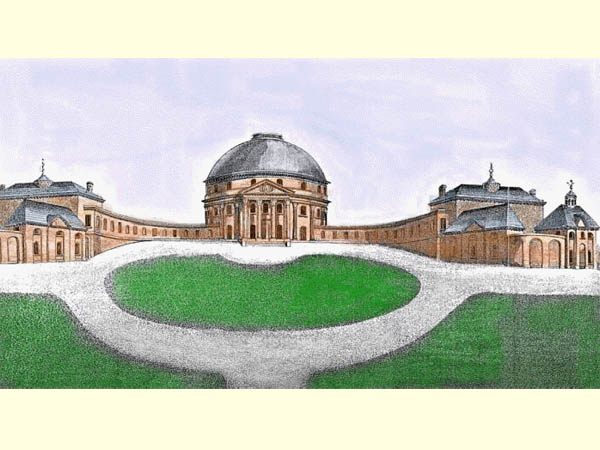

Hervey also built what must have been one of the greatest gems of British Palladian architecture, Ballyscullion House. Alas, it is no longer extant, but has been reduced to a respectable if far less elaborate mansion. (Source) For a 3D model, see here.

If there’s one thing for certain, it’s that Anglicanism as lived in history is not a dry religion.

Allow me to indulge in a bit of crude cultural observation. It occurs to me that the national church of the English would inevitably partake of that quintessential English quality – eccentricity. Americans don’t produce real eccentrics. We breed individualists and, less commonly, outright weirdos. But the great British loon is mostly unknown to us. Eccentricity requires a certain localism, even an urban one, that has been mostly lost in the sprawling homelands of the American empire. Suburbs don’t produce eccentrics.

And more to the point, why should strangeness be so unwelcome in the Church? Why should the Church be bland and conformist and comfortable? Why must we labor on through the nauseatingly boring bureaucratic lingo and platitudinous sound-bites that so often seem to make up the bulk of our ecclesisatical discourse? Where is the sizzling fire cast to earth? Where is the light and heat of the Holy Ghost? In reviewing the proceedings of the recent Youth Synod, I was dismayed to find so little that genuinely spoke of the sacred. It so often seems that our Bishops are more interested in crafting a Church of the self-righteous liberal bourgeoisie than they are in the Church that Jesus left to His Apostles.

Eccentricity may not be a strategy, but it’s at least has the potential to become a reminder that the supernatural reality is completely other. As that Doctor of the Church, David Lynch, once said, “I look at the world and I see absurdity all around me. People do strange things constantly, to the point that, for the most part, we manage not to see it.” Well, God does far stranger things far more often than we do. Eccentrics – especially the Fools for Christ – can speak to that.

Butler-Gallie gets at this well in his article when he writes,

Church of England with more rigour and vigour might have its appeal, but the evangelising potential of the strange increasingly appears to be a casualty of the drive to be more, not less, like the world around us. An embracing of our strangeness, failings, and folly might free us to eschew conversion via tales of our usefulness — be that in pastoral wizardry, wounded healing, or nifty management speak — and, instead, “impress people with Christ himself”, as suggested by Ignatius of Antioch (who, though not an Anglican, did share his fate with the 1930s Rector of Stiffkey, both being eaten by a lion).

…Perhaps less strangeness is a good thing. It is certainly an easier, safer thing from the bureaucratic and behavioural point of view. I’m more inclined, however, to agree with J. S. Mill — hardly a friend of the Church of England — who suggested that “the amount of eccentricity in a society has generally been proportional to the amount of genius, mental vigour, and moral courage it contained. That so few dare to be eccentric marks the chief danger of our time.” Or, to put it another way, a Church that represses its strangeness is one that is not more at ease with itself and the world, but less.

I can only applaud this point. Ross Douthat said much the same in my own communion when, in response to the Met Gala last Spring, he suggested we “Make Catholicism Weird Again.” Or what Fr. Ignatius Harrison CO was getting at when he gave that wonderful sermon on St. Philip Neri’s downright oddity. And though Flannery O’Connor may never have actually said it, I can’t help but agree that “You shall know the Truth, and the Truth shall make you odd.” Indeed, my readers will know that I have hammered on about this point ad nauseum. Butler-Gallie’s writing encourages me to keep at it until we in the Christian West more widely recognize the charism of eccentricity.

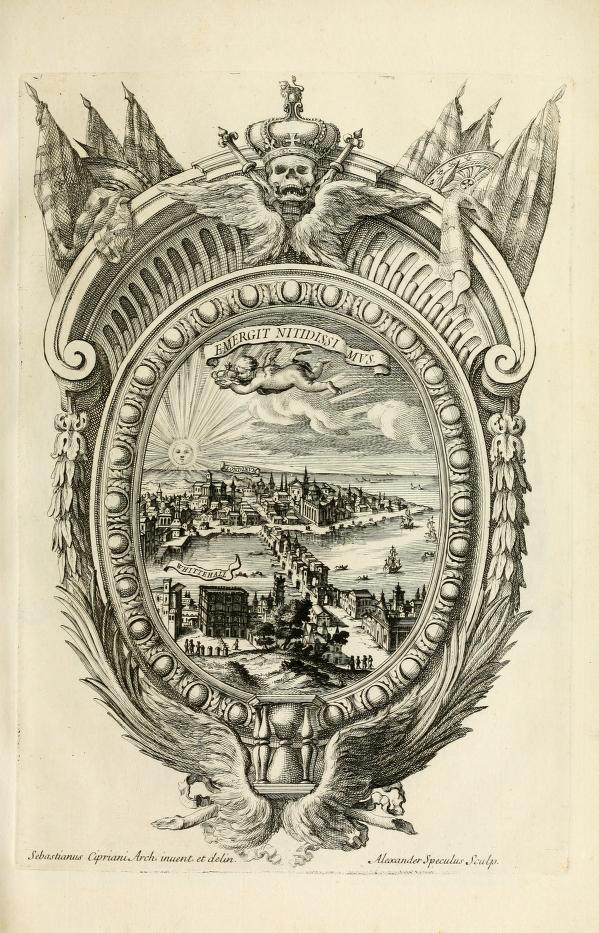

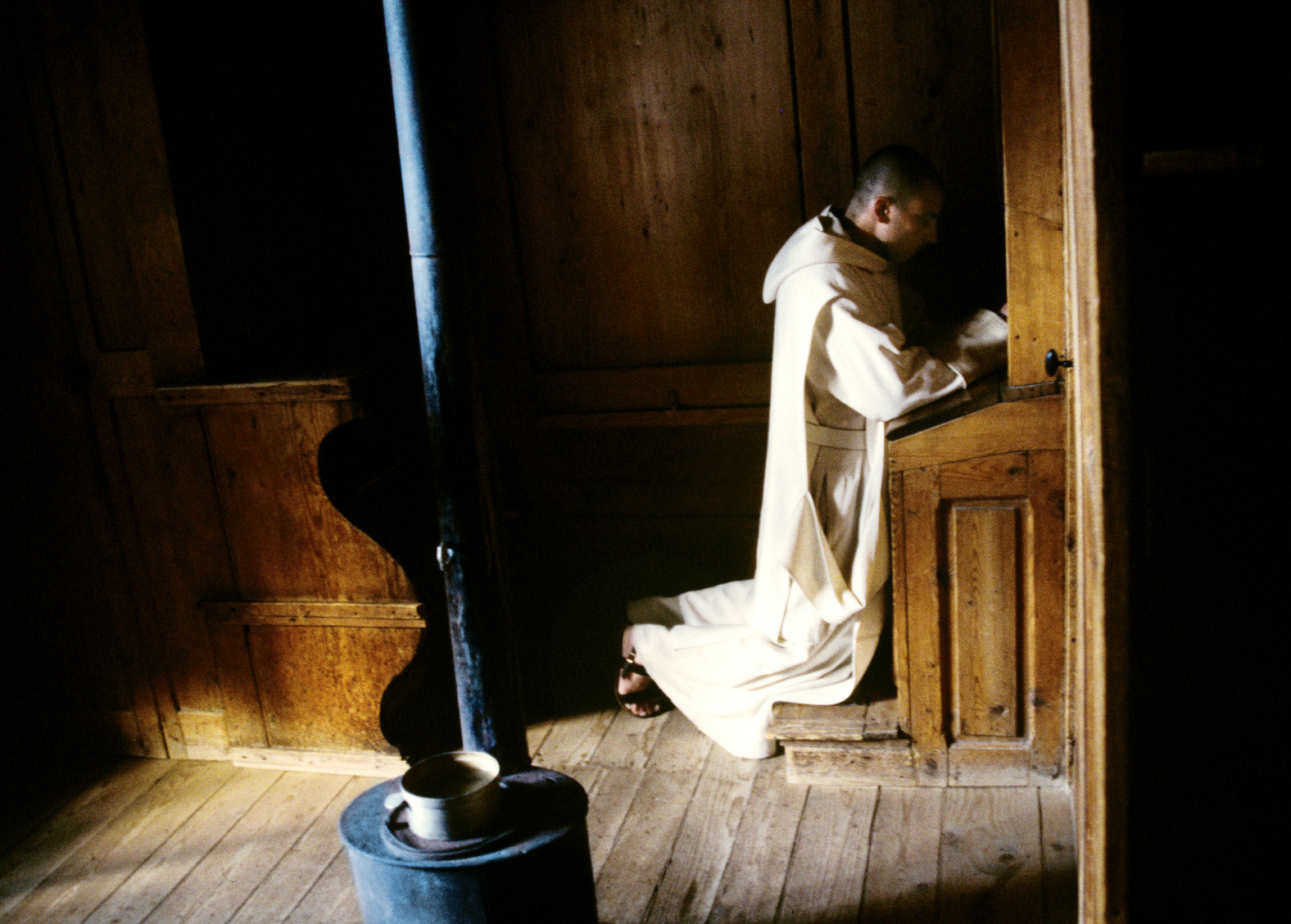

Prelates dancing to the Devil’s music. (Source)