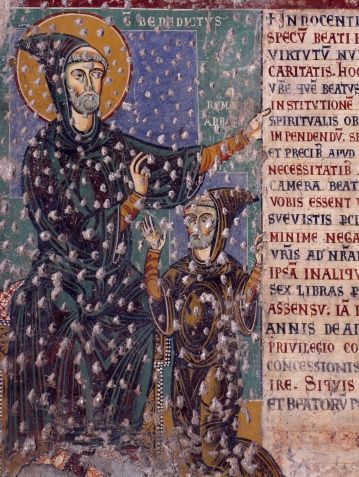

“Rome will be your Indies.” St. Philip receives his vocation from a Cistercian. (Source)

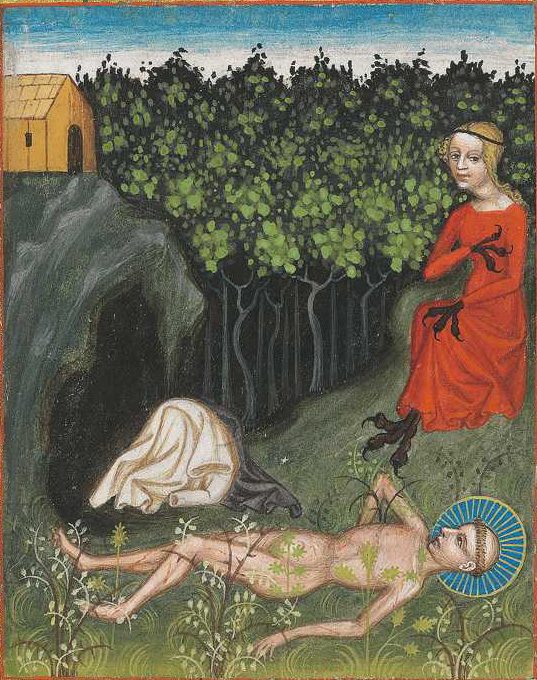

It has not been remarked upon very often that St. Philip loved the Benedictines. Monks played an important part in his life at two critical moments: first, when he decided to go to Rome, and second, when he decided to stay in Rome.

While working with his uncle Romolo in San Germano, near Naples, St. Philip would go to pray at Monte Cassino. As one author has it, “From [the Benedictines], he developed a profound love of the liturgy, the Bible and the ancient Church Fathers.” Their rich spiritual life helped cultivate a sense of God’s will, which led him to his first conversion. St. Philip quit his lucrative mercantile career with Romolo and set off for the Holy City. We shall examine his second run-in with the sons of St. Benedict later.

In considering St. Philip, we start to find similarities with other saints. Father Faber likened him unto St. Francis of Assisi; just as St. Francis was the “representative saint” of the middle ages, so was St. Philip the true saint of modernity. Cardinal Newman took another approach, tracing the influence of S.s Benedict, Dominic, and Ignatius Loyola, thereby arriving at something like a portrait by comparison. My strategy and emphases will differ somewhat from both of theirs.

Among the “great cloud of witnesses” who make up the Church Triumphant, there are an infinite number of likenesses and connections between the saints. Here and there, one spies a similarity in outlook, or devotion, or manner of life between figures who lived across centuries and continents. The eternal coinherence, the “dance” that binds them all, is the ineffable life of the Trinity in Unity. Thus, it is not surprising that when we observe similarities between Philip Neri and that great father among the saints, Benedict of Nursia, we should also find a deeper, Trinitarian resemblance.

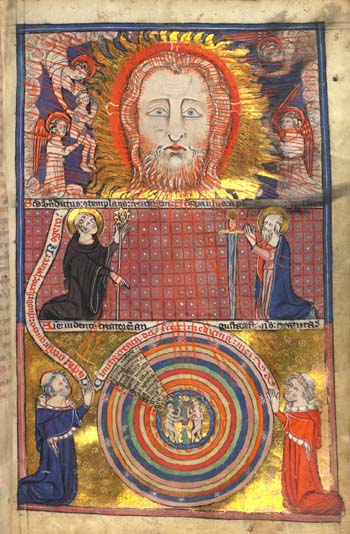

I would like to offer a meditation on the life and spirituality of St. Philip through the lens of the Benedictine vows. In doing so, I hope to shed light on the Trinitarian character of the three vows as well as St. Philip’s remarkable interior life. His Trinitarian spirituality was distinguished by the threefold experience of God that the great English mystic Richard Rolle describes in The Fire of Love: “ghostly heat, heavenly song and godly sweetness” (Rolle I.5).

Keeping all of these disparate lenses in mind, let us commence.

I. The Warmth of the Father’s Stability

St. Philip Neri was especially popular among the young men of Rome. (Source)

St. Philip was the spiritual father of many men in his own day. Palestrina, Animuccia, St. Camillus of Lellis, and others received forgiveness from him in the confessional. He was particularly kind to youth. Once, when the scholarly Baronius complained that the children with whom St. Philip was playing in the yard were too loud for his studies, St. Philip replied that he’d let them chop wood off his own back, if only they might not sin. The long-suffering Baronius accepted St. Philip’s paternal will. It was a salutary and exemplary mortification, and St. Philip knew that. It was also a lesson. St. Philip intended for his sons to live out spiritual fatherhood in the world. And they were to do it, following his own example, with intense joy.

When we contemplate the Fatherhood of God, we are struck dumb with wonder at the abyss of Being abiding in His fullness. God the Father is the immovable, the unshakeable, the indefinable One. It is from God the Father that we learn that fatherhood can only be cultivated upon presence…rootedness…constancy. And it must also blaze with the heat of love. The two qualities are mutually reinforcing. Put briefly, the warmest paternity will cool, harden, and falter if it is not sustained by stability.

St. Benedict understood this dynamic, and when he sought to compose a rule for his spiritual family, he knew that he had to incorporate it into his model. In the very first chapter of the Rule, we read of the different kinds of monks. The worst are those whom St. Benedict calls “Gyrovagues,” men who

…spend their whole lives tramping from province to province, staying as guests in different monasteries for three or four days at a time. Always on the move, with no stability, they indulge their own wills and succumb to the allurements of gluttony (Rule of St. Benedict I).

Instead, St. Benedict calls for his monks to pass their lives in one place, at one task—seeking God. Stability is so central to his vision that he doesn’t even bother writing a chapter about it. Instead, he assumes it as a necessary condition from the very beginning and lets it color his prescriptions from then on.

St. Philip was equally adamant about stability. The organization of the Oratory is a great testament to his idea of stability. Even in the early days, when he first sent some priests to San Giovanni dei Fiorentini, he required that they return to his chamber above San Girolamo—his “cenacle,” if you will—and continue with the exercises of the Oratory. When the priests finally left both parishes and moved to Santa Maria in Vallicella, the Chiesa Nuova, St. Philip imagined that his religious family would never grow beyond its four walls. He was deeply reluctant to grant the foundation of an Oratory in Naples—though it would furnish the Church with great saints such as the Blessed Giovanni Juvenal Ancina.

The basic grain of St. Philip’s idea has endured in those lands where the Oratory has flourished. Oratorians spend their whole priestly lives in one community. They can travel and work more freely than vowed religious, since they are truly secular priests, but their range of motion is restricted by the value of stability that St. Philip imposes on his sons. The quality of that stability differs from the asceticism which marked the experience of the early monks. As Newman puts it:

The Congregation is to be the home of the Oratorian. The Italians, I believe, have no word for home—nor is it an idea which readily enters into the mind of a foreigner, at least not so readily as into the mind of an Englishman. It is remarkable then that the Oratorian Fathers should have gone out of their way to express the idea by the metaphorical word nido or nest, which is used by them almost technically. (Newman, qtd. by Robinson).

As Newman said elsewhere:

…the objective standard of assimilation is not simply the Rule or any abstract idea of an Oratory, but the definite local present body, hic et nunc, to which [the novice] comes to be assimilated (Newman, qtd. on the Toronto Oratory Vocations page).

The stability of the Oratory is enlivened with a certain warmth, a familial domesticity that is adequately captured in the Italian nido. The Oratorian has his “nest” in his cell, and beyond that, his house, and beyond that, the city where God has led him. None of these becomes his “nest” by matter of location, but by the network of sacramental relationships he enters there. He is begotten anew by the paternity of St. Philip, by his immediate superiors, and ultimately, by God. The same spirit prevails in the very best monastic houses, as any visitor to Silverstream Priory or the Monastero di San Benedetto in Monte or Stift Heiligenkreuz or Clear Creek Abbey or L’Abbaye Sainte-Madeleine du Barroux can attest. Dom Aelred Carlyle’s Caldey Island had just such a sensibility, as did Nashdom Abbey before its decline. The Oratory and the Benedictine Monastery keep alive the fire of God’s paternal love by their community life and stability in prayer.

II. The Son’s Obedient Song

The Madonna Appearing to Saint Philip Neri, Sebastian Conca. (Source)

Up to now, I have not addressed the peculiar irony in my approach. The model that St. Philip left for his sons is singular among all others in the Church in its total rejection of vows—such as those that mark the Benedictine vocation. The constitutions of the Congregation are very clear. Even if all the members around the world should take vows and only one abstain, the true Oratory would rest with that lone dissenter, and not the majority. Instead, Newman tells us, “Love is his bond, he knows no other fetter.” St. Philip trusted that bond of charity to sustain the common life he envisioned for the Oratory.

St. Philip hoped that his sons, through mortification of the intellect and an easy, friendly concord, would persevere in the love that was their peculiar vocation. Just as voices unite in harmony for no better end than beauty, so might we describe the Oratorian ideal as a kind of “song”—Rolle’s second experience of God. The liturgy for the Sixth Sunday in Easter illustrates this point admirably. The Introit (Vocem iucunditatis annuntiate), Psalm (Let all the earth cry out to God with joy), and Offertory (Benedicite gentes Dominum) all refer to song as the properly obedient response to God’s grace. The truth and beauty of that good song is attractive to souls made weary by the heavy dross of the world. St. Philip knew this fact well, and he employed some of the leading composers of the time—Palestrina and Animuccia—to write music for the exercises of the Oratory.

Moreover, one could almost imagine that the first reading, which mentions the Apostle Philip, was really intended to tell us something about the life of the Joyful Saint:

Philip went down to the city…and proclaimed the Christ to them. With one accord, the crowds paid attention to what was said by Philip when they heard it and saw the signs he was doing…There was great joy in that city. (Acts 8: 5-8 NAB)

Similarly, the Epistle calls to mind St. Philip’s singular mystical life. We read, “Sanctify Christ as Lord in your hearts,” (1 Pet. 3: 15-18 NAB). And how are we, like St. Philip, to go about sanctifying Christ in our hearts? The Gospel tells us:

If you love me, you will keep my commandments. And I will ask the Father, and he will give you another Advocate to be with you always, the Spirit of truth, whom the world cannot accept, because it neither sees nor knows him. But you know him, because he remains with you, and will be in you. (John 14:15-17 NAB)

Christ is preeminently the man who responds with a song of obedience, and St. Philip follows his lead. And what do St. Philip and his sons sing in their common life? What but the praise of God? What but the Divine Word, the Logos, Christ made present in prayer and scripture and sacrament? Indeed, Eliot’s description of “every phrase/And sentence that is right” could apply just as well to the Oratorian life:

…where every word is at home,

Taking its place to support the others,

The word neither diffident nor ostentatious,

An easy commerce of the old and the new,

The common word exact without vulgarity,

The formal word precise but not pedantic,

The complete consort dancing together

(Little Gidding V)

The life of the Benedictine monk is not so seemingly free. He has one work, the liturgy, the Opus Dei. This one task is the first and final way that the Benedictine fulfills his vow of obedience to Christ. As Chapter 5 of the Holy Rule has it: “The first degree of humility is obedience without delay. This is the virtue of those who hold nothing dearer to them than Christ” (Rule of St. Benedict V). The eleven degrees that follow build upon this cornerstone, marked as it is by the love of Christ. It is a love that conforms the monk to the obedience of Christ crucified. The wicked Sarabaites that St. Benedict describes in Chapter 1 are chiefly marked by their unwillingness to obey:

They live in twos or threes, or even singly, without a shepherd, in their own sheepfolds and not in the Lord’s. Their law is the desire for self-gratification: whatever enters their mind or appeals to them, that they call holy; what they dislike, they regard as unlawful. (Rule of St. Benedict I).

St. Philip knew how to obey. When he was under suspicion of heresy, he immediately ceased his labors in submission to the Papal investigators until he knew the outcome. He only resisted when it came to the cardinalate, which he always resolutely refused. Once, upon receiving the Red Hat, he made jokes about the honor and laughed it off as if it were nothing—in the very presence of the Pope! Exasperated, the Holy Father decided to grant St. Philip’s wish, and did not insist on the appointment.

But he also obeyed the voice of God through other figures, such as when he formally received his vocation. Hearing the many stories of St. Francis Xavier in the East, St. Philip determined to set out for India. But he decided to wait and test the calling with the advice of another man he trusted.

In Rome, there is a Cistercian monastery called the Tre Fontane, which takes its name from the legend that when St. Paul was martyred, his head bounced three times. It is said that three fountains miraculously sprang up from the earth where his head fell. Later, a house of religion was founded there. It was to this monastery that St. Philip went to consult a well-respected monk known for his spiritual insights. The monk listened to St. Philip’s situation, and told him to return later. When St. Philip came back to the Tre Fontane, he had his answer—“Rome will be your indies.” He never again desired to leave the Holy City. Cardinal Newman tells us that the monk did this under the spiritual guidance of St. John. How appropriate that the Apostle so intimately tied to the Second Person of the Trinity should teach St. Philip to imitate Christ’s obedient humility!

III. The Sweetness of the Spirit’s Conversatio Morum

The Holy Spirit made the heart of St. Philip sacramental while on this earthly journey. (Source)

Few saints have such a manifest intimacy with the Holy Spirit as St. Philip Neri. Biographers and commentators throughout the centuries have always noted the peculiar affinity between St. Philip and the Third Person of the Holy Trinity.

When St. Philip first came to Rome, he spent most of his nights praying in the catacombs. He drew surpassing sweetness from this salutary solitude. For him, Rome was not just a (recently sacked) city of decadent palaces, picturesque ruins, and opulent vices. Rome was a landscape marked by the work of the Holy Spirit through human history. The catacombs reminded St. Philip of the Church of the martyrs.

It was on one of these vigils that St. Philip experienced a visitation by the Holy Spirit. He came to the catacomb of St. Sebastian on the night before Pentecost. While praying, the Holy Spirit descended upon him. Fr. Philip G. Bochanski of the Oratory describes the scene well:

As the night passed, St Philip was suddenly filled with great joy, and had a vision of the Holy Spirit, who appeared to him as a ball of fire. This fire entered into St Philip’s mouth, and descended to his heart, causing it to expand to twice its normal size, and breaking two of his ribs in the process. He said that it filled his whole body with such joy and consolation that he finally had to throw himself on the ground and cry out, “No more, Lord! No more!” (Source).

Throughout his life, St. Philip would report an unremitting heat throughout all of his body, though always most intense around his heart. Even in the dead of winter, he’d be so warm as to freely unbutton his collar when everyone else was shivering. Pressing someone’s head to his breast, letting him hear his heartbeat and feel the miraculous warmth, was enough to convert even the most hardened and impenitent sinners. We can say with no exaggeration that the Holy Spirit made St. Philip a living sacrament. He became a fountain issuing forth graces. He bore all of the sweet fruits of the Holy Spirit. As Fr. Bochanski puts it, “St Philip was convinced and constantly aware of the presence and action of the Holy Spirit in him and through him…He was sure that he had received the gifts of the Holy Spirit, and this assurance set him free to bear the Spirit’s fruits.”

St. Philip’s special relationship with the Holy Spirit drew him into an almost uncontrollable ardor of love for the Eucharist. He was a great mystic of the Blessed Sacrament. Under St. Philip’s direction, the Roman Oratory popularized the Forty Hours Devotion of Eucharistic Adoration, an important precursor for later efforts at Perpetual Adoration. In spite of his wise suspicion of visions and miracles, he was granted innumerable ecstasies. These would usually come in some connection with the Eucharist. St. Philip had jokes read to him in the sacristy as he vested, as he had a very realistic fear of entering a sweet trance of joy before the Mass even began.

In his old age, St. Philip was allowed to give free reign to these Eucharistic ecstasies. By special permission of the Pope, he would say his Mass only in a private chapel on the top floor of the Vallicella. At the consecration, he would kneel down before the altar. The servers would close the windows, shut the door, and place a sign on the handle which read, “Silence! The Father is saying Mass.” Then, in darkness and silence, St. Philip would commune with the Eucharistic God for upwards of two hours. When he was done, the servers would ring a bell, the sign on the door would be removed, and he would continue the Mass as if nothing had happened.

In all of these phenomena, we may be tempted to draw a contrast with the staid, rhythmic, simple spirituality of St. Benedict’s Rule. Not so—for we must examine why St. Philip was given the singular graces that marked his life in the Holy Spirit.

The third vow that St. Benedict demands of his sons is Conversatio Morum, the conversion of manners (Rule of St. Benedict LVIII). The monk enters the monastery that he might “seeketh God,” and seek Him fully (Rule of St. Benedict LVIII). Like all Christians, he is after deification. But unlike most of us, he is called to theosis by shunning the distractions of the World. He can only do this by entering into the sacrifice of the Eucharistic Christ, whom he adores in the liturgy that marks the hours of every day. The Benedictine vocation is, at its heart, life made explicitly Eucharistic.

Dom Mark Daniel Kirby of Silverstream, building upon the work of the Blessed Abbot Columba Marmion and Mother Mectilde de Bar, has put the point admirably. Among many other similar passages, we find in a poem from 2011:

The Eucharistic Humility of God

is inseparable from His Eucharistic Silence.

This Saint Benedict understood,

for in his Rule, the silent are humble,

and the humble silent.

This our Mother Mectilde understood

for she wanted her Benedictine adorers to bury themselves

in the silence of the hidden God,

the ineffably humble God

in the Most Holy Sacrament of the Altar.

(Source)

In the Eucharist, we find the consummation of all God’s sweetness. “O taste, and see that the Lord is sweet: blessed is the man that hopeth in him” (Psalm 33:9 DRA). It is the grand work of the Spirit, the crown of the sacraments, the dawn of the new and everlasting life. Just as Richard Rolle passed into “the most delectable sweetness of the Godhead,” so too does the monk return each day to the Eucharist to drink of the Spirit’s epicletic sweetness (Rolle I.5).

And St. Philip, with his Eucharistic ecstasies and his intimacy with the Spirit, knew that sweetness better than we can possibly imagine. The sweetness of the Holy Spirit transformed him into an instrument of grace, a human sacrament whose own manners were deeply converted and who aided many along the same journey. It is little wonder that Oratories and Benedictine monasteries remain centers of reverent and beautiful celebration of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass.

Conclusion

Portrait of St. Philip Neri. (Source)

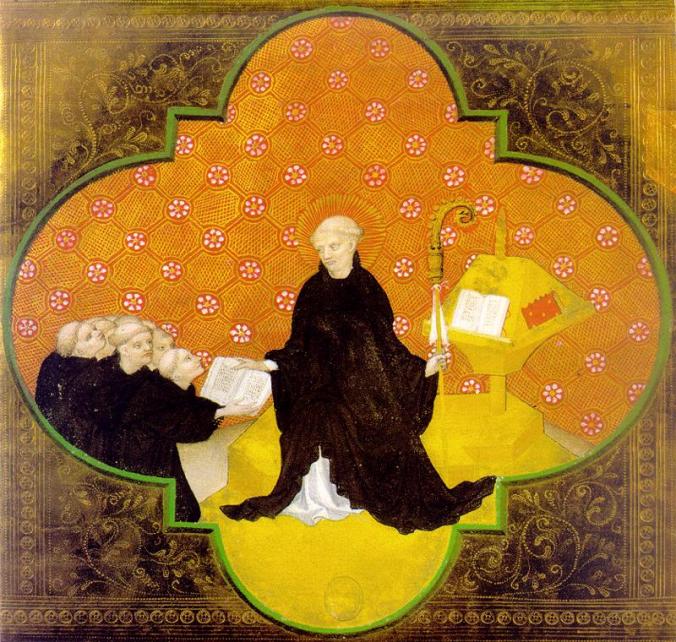

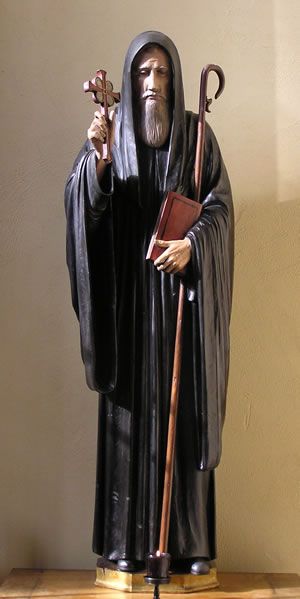

Portrait of St. Benedict. (Source)

Many writers have found in St. Philip Neri the likeness of other saints, including those predecessors whom he admired, the contemporaries whom he loved, and the innumerable great saints who followed in the generations since he went on to immortal glory.

Yet is any resemblance so striking, and so Trinitarian, as that between the Father of the Oratory and the Father of Monks? In both, we find the very image of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. In both, we can see the marks of stability, obedience, and conversion of manners. And in both, we detect the surpassing heat, song, and sweetness which Richard Rolle describes as indicative of a true encounter with God.

By their prayers, may we someday share that eternal encounter.

The Holy Trinity with St. Philip Neri in Glory, Francesco Solimena. The figure at left is probably the Benedictine Oblate, St. Francesca Romana. The painting, originally intended for the Naples Oratory, now hangs in the Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology at Oxford (Source).

St. Benedict in Glory, c. 1500. Artist unknown. (Source)