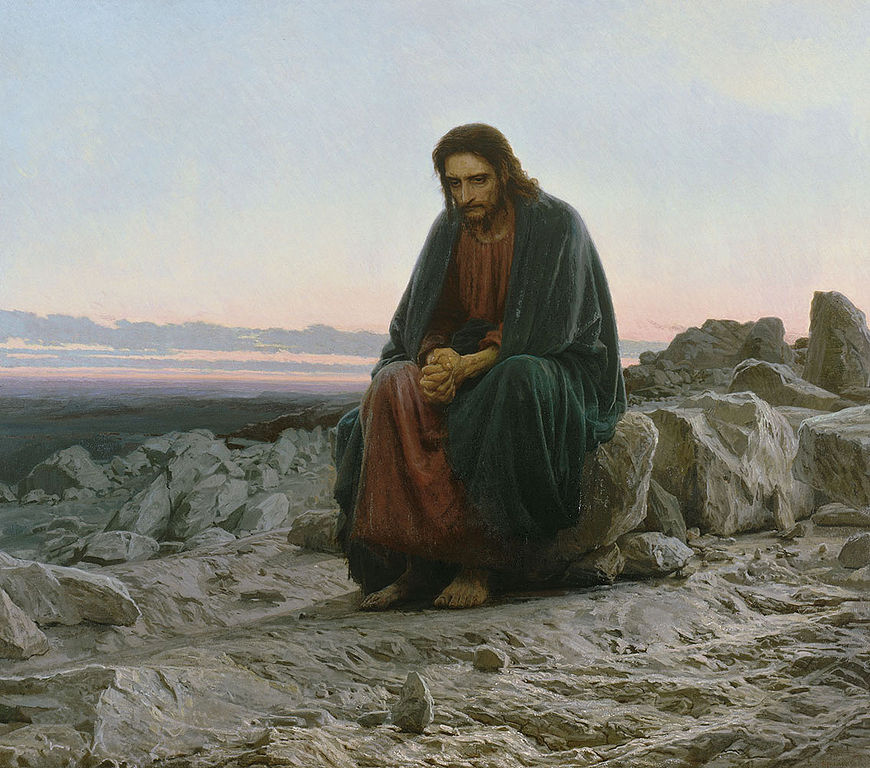

“Jesus Christ will be in agony until the end of the world” – Blaise Pascal

“We shall not be blamed for not having worked miracles, or for not having been theologians, or not having been rapt in divine visions. But we shall certainly have to give an account to God of why we have not unceasingly mourned.” – St John Climacus

Recently I have had occasion to consider the role of joy in the Christian life. While I don’t believe that any particular emotions as such are intrinsic to Christianity, I sometimes feel that there is in the Church’s culture a kind of low-level idolatry of affective joy that makes it a good in itself and, more poisonously, demonizes those who do not share in it. This rather shallow (and ultimately false) view of joy as relentless and mandatory happiness has at times eclipsed the demands of the Cross, and has little to offer the suffering, the infirm, the distressed, the depressed, the sorrowful, the anxious, and the temperamentally gloomy. Are they to be excluded from heaven if they cannot force a smile? This soft and implicit Pelagianism of the emotions is a greater discouragement to souls than an honest reckoning with the sorrows of life and the terrible demands of the Cross.[1]

So, I thought I would put down a few very brief meditations on true and false joy. I would not wish to speak in absolute and general terms, but rather, out of the fullness of my heart, and all that I – a mere layman – have gleaned from seven years in the faith, the reading of Scripture, and the study of the Church’s spiritual history.

St. Paul tells us that joy is a fruit of the Spirit; he does not promise us that we shall have all those fruits at all times, or that they grow in us for own profit alone.[2] If I may alter the metaphor a bit for illustrative purposes (without in any way denying the truth St. Paul teaches), I would say that joy is the flower, and not the root or the fruit, of the Christian life as such.[3] It is chiefly given to us by God so that we might advance His Kingdom. Like the pleasant blooms of spring, joy is meant to attract souls who do not yet know the grace of God, and thereby to spread the life of the spirit. As soon as we have it, we must give it away. It is like an ember in our hands – giving light and heat, but liable to burn us if we hold on to it. For who are we to keep it, we who are nothing? And so, we should not be surprised if even this true joy is fleeting, and given to us only in rare occasions as a special grace. For the joy of God is not like the joy of the world. The former is rare as gold, and the latter as common as fool’s gold.

And as fool’s gold will not purchase what true gold can buy, so does a false joy fail in this paramount duty of conversion. We should not force ourselves to seem happier than we really are; a certain virtuous attempt at good cheer in the face of sorrow is always welcome, and we generally should not air our griefs too freely. I believe this virtue, built upon a detachment from our worldly disposition, is what the Apostle refers to when he tells us to “Rejoice always.”[4] But let us not delude ourselves into thinking that this human cheer can ever compare with the supernatural joy that comes only from God, and which many just souls have not been granted. To do so approaches dishonesty, both to ourselves and to our neighbor. Let us not pretend that our faith cheers us more than it really does; let us instead recognize that it promises us suffering, and a yoke that, though light, is nevertheless still a yoke.[5] And under that yoke, someone else will lead us where we do not wish to go.[6]

Joy is only true if it comes from, is ordered to, and brings us back to the Cross. The joy that God gives is always stained with the Precious Blood. But even then, we are not entitled even to this joy in our present life; rather, we are given the Cross as our inheritance. For what is the world if not a land of false joys? They come from nothing, they come to nothing; in their essence, they are nothing. Well and truly does the Sage condemn it all as vanity.[7] Well and truly does the Psalmist speak of it as “the valley of the shadow of death.”[8] Well and truly do we address the Mother of God from “this valley of tears.” We can do no other.

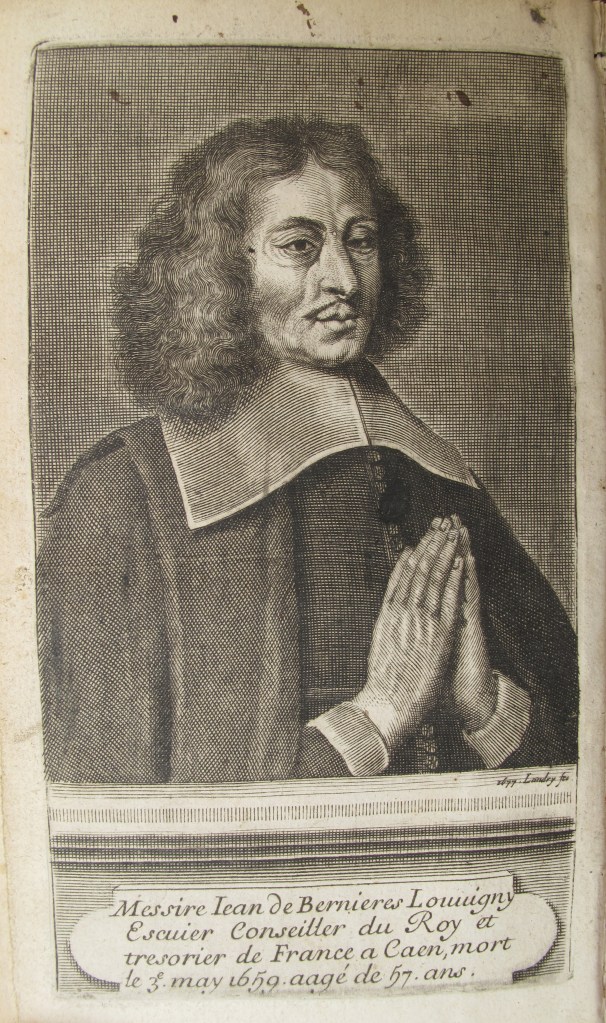

This life of the Cross is a gradual annihilation – what the French call anéantissement – a fearsome but salutary tutelage in humility and in the growing recognition of our own nothingness. To live and die on the Cross is to say every day with St. John the Baptist that “He must increase, I must decrease.”[9] Yet how hard this is! We lose sight of the fact that at the end, when we are nothing again, we can grasp the God who is No-Thing, the One who is beyond the traps, illusions, trinkets, clutter, disappointments, and, indeed, the joys of this world. We efface ourselves now so we may one day face Him. We mourn our sins today so we may rejoice in attaining God on the last day.

That is the true joy of the Cross – that, in mounting it, we can see God. But how rare is such a grace in this life! Most of us are caught up into the business of the world. Most of our lives are a long distraction. Most of us will only achieve the vision of God after the sorrows of this life and the pains of purgatory. And so, let us never forget that to be a Christian is to let Christ suffer and die in us, so that one day, we too may rise with Him.[10]

[1] James 4:4.

[2] Galatians 5:22-23.

[3] The root is faith, and the fruits are redemptive suffering and acts of charity.

[4] 1 Thessalonians 5:16.

[5] Matthew 11:28-30.

[6] John 21:18.

[7] Ecclesiastes 1:2.

[8] Psalm 22 (23): 4.

[9] John 3:30.

[10] Galatians 2:20; 2 Corinthians 4:11; 2 Timothy 2:11; Philippians 1:21