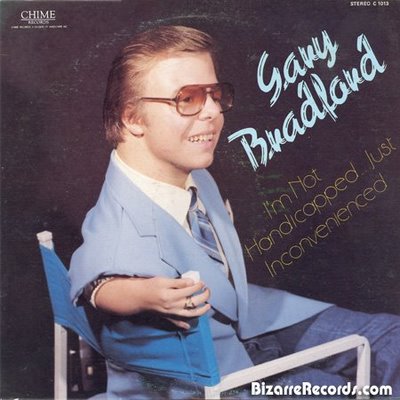

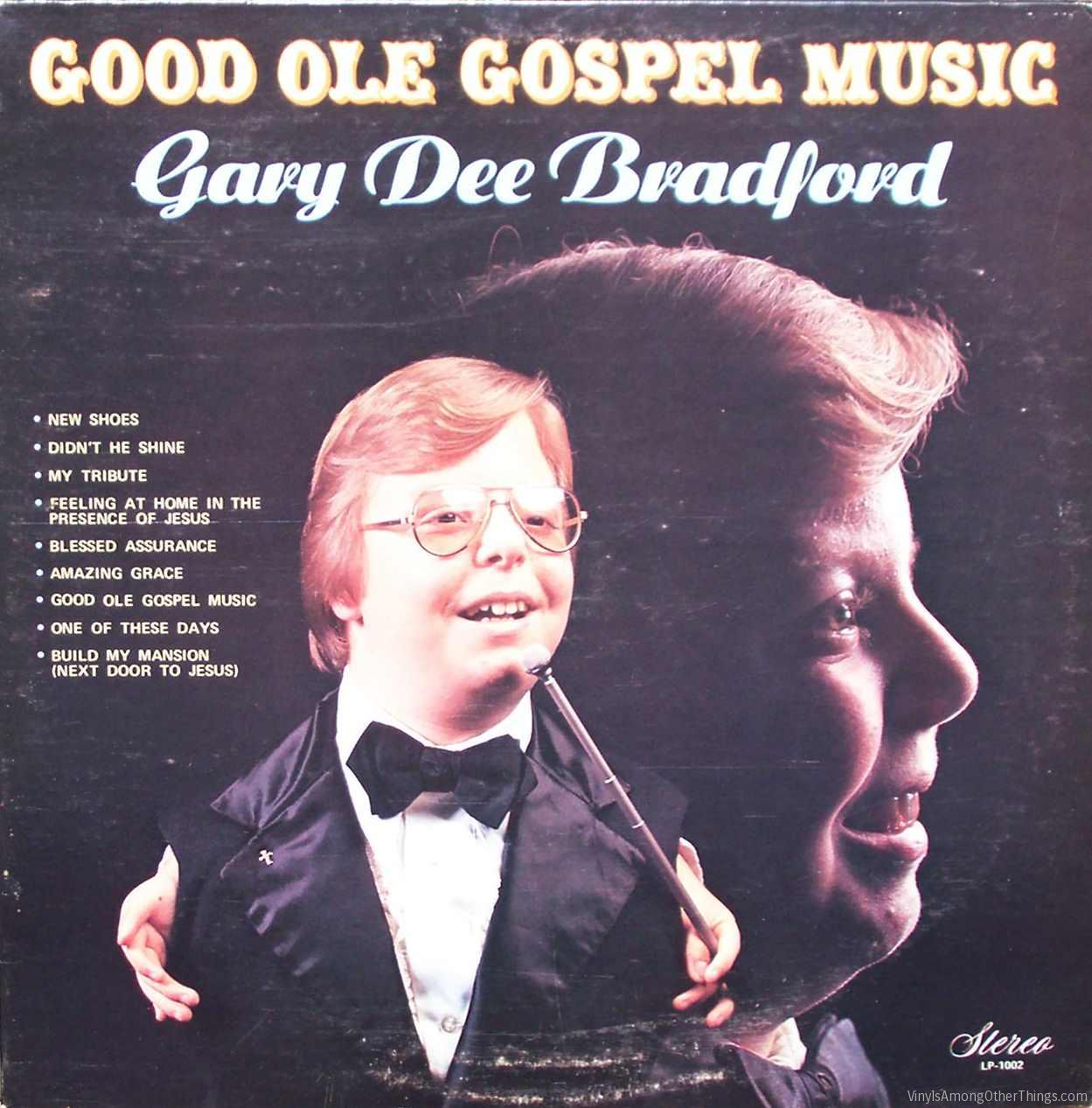

Recently I came across a very strange song from an equally bizarre album. The song was “I’m Not Handicapped, Just Inconvenienced,” by Gary Dee Bradford. It was on his 1979 album of the same title. The piece is a chilling mix of bad ventriloquism, preachy Carter-era Evangelicalism, and awkwardly poor singing. Which means, of course, that I loved it.

I soon found out that Bradford, who suffers from a rare physical disability called phocomelia (he lacks arms and has hands at his shoulders), produced a few other albums. Although he produced his most recent work in 2002, most of his output came in the 1970’s and 80’s. In one of the only other songs by Bradford I can find online, 1977’s “Good Ole Gospel Music,” we can hear the prepubescent Bradford sing in a high and eerie voice about the superiority of his chosen genre:

It is the sweetest love song

Ever heard by mortal man.

If we had more Gospel Music

We’d have a better land…a better land!

It’s catchy, I have to admit. Even if it’s not exactly Mozart.

It would be easy to make fun of the sheer cheesiness of Bradford’s records and write them off as one more episode in the history of odd music. But in fact, Bradford’s albums deserve more respect than that. They tell us something about the history and spirituality of mid-20th century American Christianity. Bradford wasn’t working in a vacuum.

American Gospel music, particularly that brand of Gospel that flourished in the predominately white churches of the mid-century South, has roots in the musical traditions of Appalachia. One of the most common and longstanding song forms found there is the ballad. Appalachian ballads often tell stories of woe and redemption, sadness and hope. When given a religious inflection, they become the musical versions of faith-sharing, testifying to the work of God in redeeming poor sinners. They are also the Protestant equivalents of the Catholic world’s longstanding folk ex voto tradition.

An example of a Mexican ex voto, 1853. (Source)

The ex voto is a little painted image offered by a devotee in thanksgiving to Christ, the Virgin, or a saint for a perceived blessing. Usually, the scene of the miracle is depicted in fairly simple (or what the art critics would call “naive”) terms, with a short, handwritten narrative describing the incident below. They are emphatically not “fine art.” Ex votos are the result of folk piety, and they depict the most fundamental relationship of the worshiper and the supernatural, the body and the invisible world, faith and crisis.

There’s also a uniquely New-World flavor to the ex voto form. While examples abound from most historically Catholic cultures, the most exemplary tradition of ex votos can be found in Mexico. Indeed, the ex voto has become one of the country’s national art forms, often stylized and reinterpreted by contemporary artists. Frida Kahlo even collected them.

We can see the same kinds of spiritual impulses behind a whole wave of calamity-themed songs in mid-to-late-20th century Gospel. Perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised that, in a Protestant context, the ex voto takes an audible rather than visual form. Take, for example, Jerry D. Brown’s A Crippled Boy’s Prayer and The Fuller Family’s slightly earlier but almost identical A Little Crippled Girl’s Prayer.

Not a great song, but it makes sense as a sort of ex voto. (Source)

Sometimes, the album as a physical object mirrors the makeup of an ex voto. The back of the albums often carry long messages of praise and thanksgiving in spite of the various afflictions the artists suffer from. For example, on the back of A Little Crippled Girl’s Prayer, we read the words of wheelchair-bound Marsha Fuller:

It’s so great to be a Christian and serving such a great God. He has given so much to me, for most children with my disease lead a quiet life and never have the opportunities that I have had. At the age of three He gave me a voice to sing with. And three years later God inspired me to write two songs. Since then, I have written four other songs and made two recordings. He has also blessed me in other ways. He gave me a wonderful Mom and Dad whom have loved and cared for me so much. He gave me a wonderful brother, Gene. You don’t find too many twenty-year-old men who loves to sing for the Lord the ways he does. As a family we have had rough times together. Sometimes we didn’t know where the next meal was going to come from because of hospital bills, but, God has always pulled us through. Our house might not be the biggest and our clothes might not be the finest, but as long as we stay true to Jesus someday we’ll have a mansion that outshines the sun. We truly hope that you will be blessed by our message in song to you. Yours in Christ, Marsha Fuller

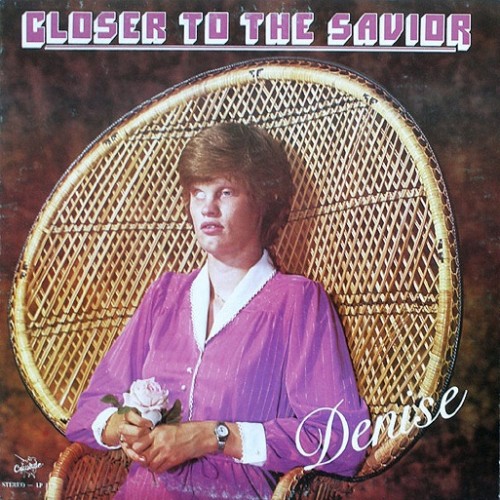

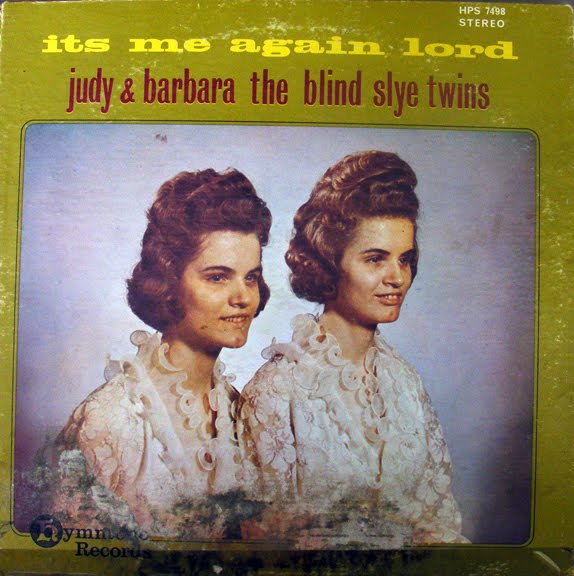

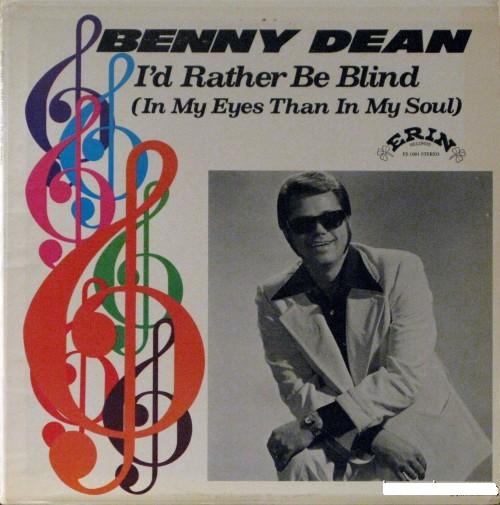

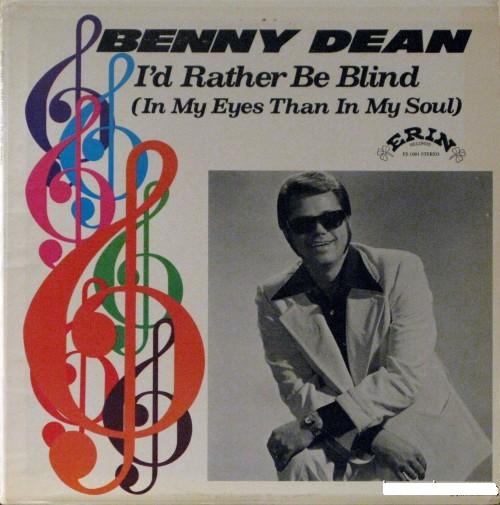

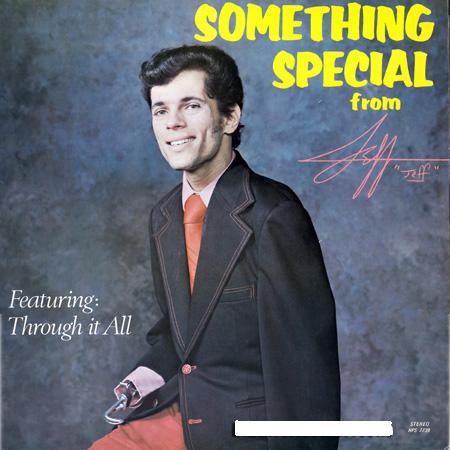

There was a veritable cottage industry of Christian albums by blind, amputee, or otherwise disabled artists that flourished in the middle of the twentieth century. To give a few examples:

Benny Dean’s I’d Rather Be Blind (In My Eyes Than In My Soul). A bit on the nose. (Source)

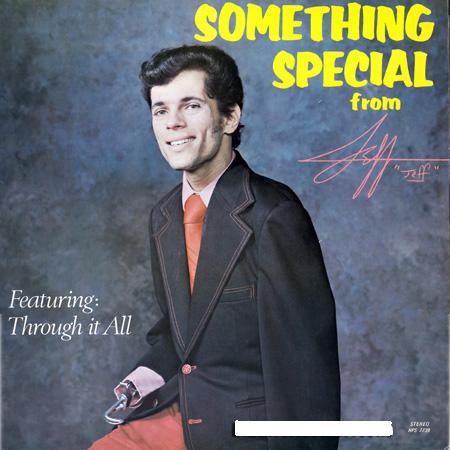

Here’s Something Special from Jeff Steinberg. Note the hook. (Source)

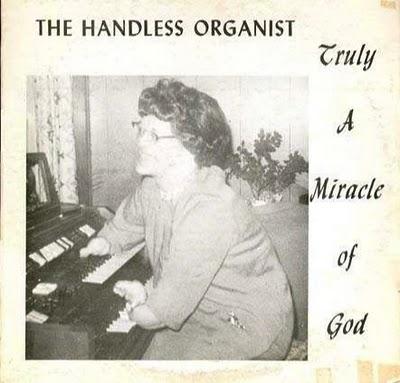

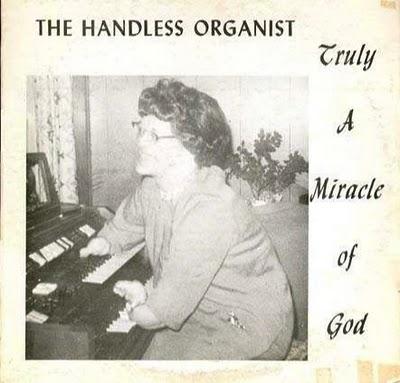

“Truly a Miracle of God!” (Source)

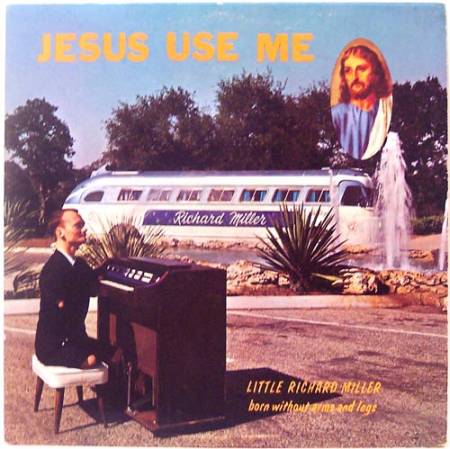

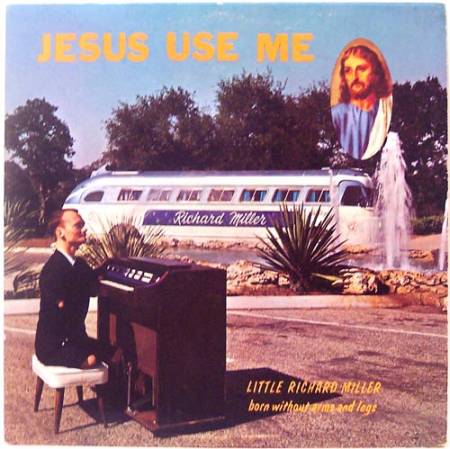

Another offering from “Little Richard Miller,” this time with cover art that closely if unintentionally replicates the ex voto model. The full album is online for your listening pleasure. (Source)

These musical works differ from the mainstream of Protestant aural culture in that, even when the songs themselves are classic hymns or are just covers of more obscure songs by disabled artists, they take on a new, personal, and highly-charged meaning in the context of public disability. The artists are not just performing music, they are performing both disability and Christianity – indeed, they perform their disability precisely as the core of their Christianity, and their Christianity as intimately bound up with their disability. The singer born without arms or the blind crooner or the organist missing her hands can all achieve a new status as an icon of model Christian disability. Their performance points towards the hope of a transfiguration that surpasses disability in the kingdom of heaven. Moreover, their physical or mental incapacity is often an implicit analogy for the spiritual deformation, blindness, or weakness found in the more conventional Gospel ballad. The healing of both comes from Jesus.

Mary Douglas, among other anthropologists, has noted that the body physical is often used as an analogy of the body politic. The symbolic representation of the individual corpus speaks to the social body at large – culturally-coded anxieties about the limits of the physical body frequently point to an underlying anxiety about threats to the community. Should it surprise us that the most visible flowering of this disability-obsessed genre came at a time when the culture wars were starting to animate the full force of Southern and Midwestern Protestantism into a politically active bloc with an agenda for cultural change? Surely that socio-political context stands behinds Gary Bradford’s “better land.” The Evangelical doom song, with perhaps its best representatives in the Louvin Brothers, rose to prominence at much the same time.

The fundamentalist folk spirituality that these songs present are a major cultural context in the wonderfully disturbing, deeply Catholic work of Flannery O’Connor. In her short story “A Temple of the Holy Ghost,” she injects it into her description of a Southern freak show. An intersex person addresses two crowds – one made up of men, another of women – before displaying their unusual genitalia. The freak says,

“I’m going to show you this and if you laugh, God may strike you the same way.” The freak had a country voice, slow and nasal and neither high nor low, just flat. “God made me thisaway and if you laugh He may strike you the same way. This is the way He wanted me to be and I ain’t disputing His way. I’m showing you because I got to make the best of it. I expect you to act like ladies and gentlemen. I never done it to myself nor had a thing to do with it but I’m making the best of it. I don’t dispute hit.” Then there was a long silence on the other side of the tent and finally the freak left the men and came over onto the women’s side and said the same thing. (The Collected Stories of Flannery O’Connor 245).

Later, they lead a kind of religious service centered on their own experience of God’s Providence.

She could hear the freak saying, “God made me thisaway and I don’t dispute hit,” and the people saying, “Amen. Amen.”

“God done this to me and I praise Him.”

“Amen. Amen.”

“He could strike you thisaway.”

“Amen. Amen.”

“But he has not.”

“Amen.”

“Raise yourself up. A temple of the Holy Ghost. You! You are God’s temple, don’t you know? Don’t you know? God’s Spirit has a dwelling in you, don’t you know?”

“Amen. Amen.”

“If anybody desecrates the temple of God, God will bring him to ruin and if you laugh, He may strike you thisaway. A temple of God is a holy thing. Amen. Amen.”

“I am a temple of the Holy Ghost.”

“Amen.”

The people began to slap their hands without making a loud noise and with a regular beat between the Amens, more and more softly, as if they knew there was a child near, half asleep. (Ibid., 246)

O’Connor, who suffered from lupus herself, draws a parallel between the freak’s preaching and Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament. In the two episodes, we can perceive both the sovereignty of God’s Providence and the sacramental capacity of matter to bear God.

It strikes me as intuitively sensible that O’Connor should have chosen precisely this story to contrast Protestant and Catholic music. Early on in the story, two young Church of God men try to woo a pair of Catholic sisters by singing a Gospel hymn, complete with guitar and harmonica. The girls, who have been educated at convent school, bite back their giggles and respond with the Tantum Ergo. One of their suitors is more right than he knows when, puzzled and slightly disapproving, he calls it “Jew singing.” The two forms of music, though standing in an apparent contradiction, together anticipate the underlying sacramental truth presented by both the Protestant and Catholic services that conclude the story.

O’Connor makes much of Protestant devotional culture in one of her novels, The Violent Bear It Away (1955). It is the story of a boy called to prophesy, of his skeptical schoolteacher cousin, and of the battle they wage for the soul of a mentally disabled child. At one point, we come to the performance of a family of traveling musical missionaries. The high point of the act comes when their little daughter emerges from behind the curtain to preach a rousing sermon. In the course of her preaching, she delivers what may be the book’s central message:

“I’ve seen the Lord in a tree of fire! The Word of God is a burning Word to burn you clean!…Burns the whole world, man and child…none can escape…Are you deaf to the Lord’s Word? The Word of God is a burning Word to burn you clean, burns man and child, man and child the same, you people! Be saved in the Lord’s fire or perish in your own! Be saved in…” (The Violent Bear It Away 134-35).

O’Connor is fond of granting the most clear-eyed spiritual vision to the children in her stories. Many have profound experiences of grace that mark them forever, or they bear testimony of the invisible world’s dangerous immediacy to more skeptical characters.

This album makes me think of O’Connor’s 1955 The Violent Bear It Away. (Source)

That includes O’Connor’s disabled children. “The Lame Shall Enter First,” one of O’Connor’s most emotionally crushing short stories, is a close companion to The Violent Bear It Away. It tells the story of a well-meaning social worker, Sheppard, who takes in a clubfooted juvenile delinquent, Rufus Johnson, hoping to steer him towards a productive life. Although he can overlook Rufus’s constant spite, Sheppard is exasperated by the fundamentalist beliefs he clings to. Rufus is convinced he is going to hell, and starts to talk about it with the social worker and his impressionable young son. He steadily grows into the role of preacher even as Sheppard tries desperately to “flush that out of [his] head.” I won’t get into any spoilers, as the story has a wrenching, unforeseen climax. I’ll just say that Sheppard finally realizes he has failed only when Rufus cries at him,

“I lie and I steal because I’m good at it! My foot don’t have a thing to do with it! The lame shall enter first! The halt’ll be gathered together. when I get ready to be saved, Jesus’ll save me, not that lying, stinking atheist, not that…” (The Collected Stories of Flannery O’Connor 480).

Sheppard attributes all of Rufus’s bad behavior to the emotional effect of his clubfoot. But Rufus finds his one hope of salvation in the fact that he has a disability that, according to the logic of heaven, will ensure that he enters the Kingdom first. For Rufus, as for so many of the artists mentioned above, it represents both faith and hope (if not yet charity). Sheppard is too blinded by his prejudice and his loneliness to see that. The results are calamitous.

Rufus’s underlying insight speaks to a truth often forgotten in the Church’s treatment of the disabled. Those with disabilities are not “problems.” It’s true that they may have some special needs with regards to access, attention, etc. But at the end of the day, they are people who have the same basic spiritual needs as any other human beings. They, too, can embody and image Christ – often better than those of us who are blessed enough to be of both sound mind and body.

Gary Bradford himself has spoken publicly about this issue before. Some time in the late 1980’s or early 1990’s, Bradford – by then an adult – gave an interview with a Christian television network. He says,

In the past…so many of our churches, and so many of our people in our church in the past, it’s been the place for the good, the well-bodied, and the abled…And the Church isn’t to be like that; the Church is to take all.

Of course, the other great danger is to place too much emphasis on the disability and not enough on the person who has it. The “magical disabled person” should not become a trope in Christian life. We can’t load our disabled brethren in Christ with that moral freight. It isn’t fair. The disability Gospel genre fosters precisely that kind of harmful thinking; perhaps that is its greatest cultural fault.

I think we can avoid either extreme – neglect or overemphasis – by focusing instead on the individuality and personhood of every disabled Christian. Insofar as the disability Gospel song is an ex voto, it may seem to correspond to a certain type. Catholic ex votos usually do. But that’s only to the outsider who beholds the ex voto. For the one who makes it (or commissions it), the story it tells carries intense and highly particular personal meaning. Put another way; Sheppard may not grasp the hidden meaning of Rufus’s club foot, but Rufus does.

The same goes for the Protestant ex votos we find in this genre. They may seem to correspond to the demands of a cottage industry, but they all epitomize and present individual experiences. That particularity is the best thing we can take from this strange, lost genre of Christian music. There are no generic souls, abled or otherwise.