Earlier this week, I went to the Birmingham Oratory for the Feast of Bl. John Henry Newman. Fr. Ignatius Harrison, the Provost, was kind enough to open up the Oratory house to me. I must offer him my tremendous thanks for his hospitable willingness to let me see such an incredible (and, it must be said, holy) place. Likewise, I thank Br. Ambrose Jackson of the Cardiff Oratory for taking time out of his busy schedule to give me what was an extraordinarily memorable tour. I went away from the experience with a rekindled devotion to Cardinal Newman.

Your humble servant in Cardinal Newman’s own library. Photo taken by Br. Ambrose Jackson of the Cardiff Oratory. You can see Cardinal Newman’s violin case on the lower shelf of his standing desk at right.

There were many striking and beautiful sights at the Oratory – not the least of which was the Pontifical High Mass in the Usus Antiquior, celebrated by His Excellency, Bishop Robert Byrne. Even from so short an experience, I can tell that the Birmingham Oratory is one of the places where Catholicism is done well, where the Beauty of Holiness is made manifest for the edification of all the faithful. I walked away from that Mass feeling drawn upwards into something supernal, something far beyond my ken. This place that so palpably breathes the essence of Cardinal Newman is, as it were, an island of grace and recollection amidst a world—and, sadly, a Church—so often inimical to things of the spirit.

The Birmingham Oratory with the relics of the Blessed Cardinal displayed for veneration by the faithful. This photo was taken by the author shortly before Mass.

Yet amidst all this splendor, I found myself peculiarly drawn to one very quiet, very easy-to-miss relic. It lies in the little chapel to St. Philip Neri to the left of the altar; in this placement, one can see the influence of the Chiesa Nuova on Newman and his sons, who modeled their house’s customs on Roman models. And so it is only appropriate to find relics of St. Philip there in that small and holy place, so evocative of the great father’s final resting place.

The altar of St. Philip Neri, Birmingham Oratory. Photo taken by the author.

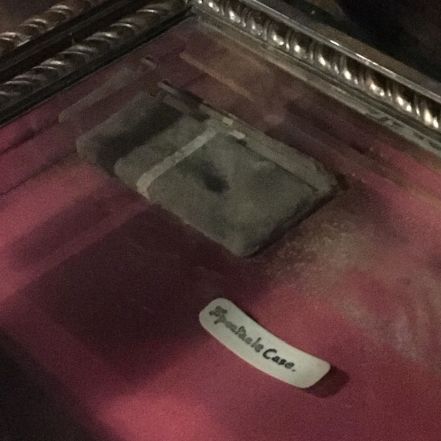

The collection of relics in the chapel are mostly second-class. These are not pieces of the body, but materials that touched St. Philip either in his life or after his death. One of these small items spoke to me in an especially strong way.

The little grey pouch you see to the left is St. Philip’s spectacle case. There is nothing terribly remarkable about it. It may not even be entirely intact, for all I know. A visible layer of dust covers the case, and a hard-to-read, handwritten label is all that identifies its use and provenance. No one comes to the Birmingham Oratory to see what once held St. Philip’s glasses. But of all the glorious relics I saw that day —some encrusted in gold, some taken from rare and holy men, some evoking the perilous lives of saints who lived in a more heroic age—it was this humble artifact that most fired my imagination.

A spectacle case is no great thing. It does not shift the balance of empires or change the course of history. But humility and nobility are close cousins all the same. Here we come upon St. Philip in his quotidian life. A saint so marvelously strange, so crammed with the supernatural, so flame-like in darting from one miracle to another, nevertheless bent his fingers to the perfectly ordinary task of opening this case and taking out his spectacles so that he might see just a little better. It is a true maxim that grace builds upon nature. We have been told of St. Philip’s many graces. Here we find him in his nature; frail and imperfect and in need of just a little aid, so like our own.

The supernatural never erases the natural, and God is never more glorified than in our weakness. The hands that took up this case and opened it and drew forth its contents, perhaps a little fumblingly from time to time, are the very same thaumaturgic hands that lifted a prince out of death and Hell so that he might make his final confession. We know the story of the miracle. How rarely do we ponder the everyday conditions of its operation! How rarely do we consider those hands in their ordinary life.

There is a tendency with St. Philip—as with many saints, and with Our Lord Himself—to reduce his life to one or two features. Some would make him an avuncular chap, always happy to laugh and thoroughly pleasant to be around, a jokester, a picture of joy and friend to all. On the other hand, we can get lost in the extraordinarily colorful miracles that mark St. Philip’s life, losing him in a fog of pious pictures and pablum. Neither captures his essence. The true middle way is to maintain a healthy sense of the bizarre—an approach that recognizes the extraordinary in-breaking of the supernatural precisely because it appreciates the ordinary material of St. Philip’s day-to-day existence. It was this view that Fr. Ignatius himself recommended, though perhaps with a greater emphasis on the “weird,” in his homily delivered last St. Philip’s day.

I was reminded of this double reality when I saw St. Philip’s spectacle case. Prosaic relics carry this two-fold life within them more vividly than those upon which our ancestors’ piety has elaborated in glass and gold. Even Cardinal Newman’s violin case is not so markedly dual in this way; after all, every instrument belongs to that human portion of the supernatural we call “art.” Music, paintings, and other aesthetic forms all lift the human soul out of itself and into another world. In some ways, they are cousins both to Our Lady and to the Sacraments, God’s masterpieces of the sensible creation. Yet a spectacle case—how utilitarian. How plain. How merely functional. There is no poetry in a spectacle case. One can imagine writing a poem about a violin—the sinuous form of the wood almost suggests it, and more so when it carries a connection with so great a man as Newman—but a spectacle case? Drab as this one is, its beauty comes only from the story it tells, from the life it once served, from the little help it gave its owner in his acquisition of beatitude.

Too often we wish to be God’s violins. In our quest for holiness, we wish to be admired, to cast our voice abroad, to give and seek beauty. These are not necessarily unworthy goals. But they are not the most important thing. Too infrequently do we turn our mind to the spectacle case. All too rarely do we seek our holiness in the gentle, quiet, everyday task of being useful, unnoticed, and present to God precisely when He needs us.

St. Philip knew how to be both, when he needed to be. May we learn to be like him in this as in so many respects.

The effigy of Holy Father Philip, Chapel of St. Philip Neri, Birmingham Oratory. Photo taken by author.

This was a touching article – so true about wanting to be the violin, and missing the great value of the spectacles case.

Thank you –

LikeLike

Pingback: THVRSDAY EDITION – Big Pulpit