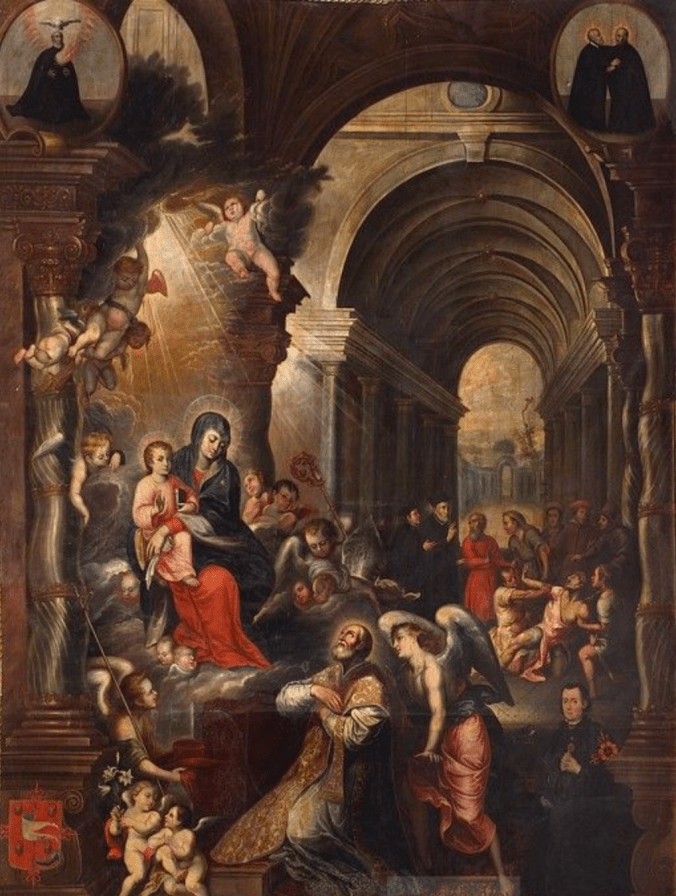

Madonna delle Grazie, Naples (Source)

Some of my readers will no doubt remember that very strange fellow I once wrote about, the Rev. Montague Summers. I have had to look at quite a lot of his orchidaceous writings recently for my research, including his poetry. Here is one such poem he wrote in Antinous and Other Poems (1907). It was written while he was still an Anglican, though it anticipates the lusciously Baroque spirituality that would mark his later writings.

Madonna Delle Grazie

Montague Summers

In the fane of grey-robed Clare

Let me bow my knee in prayer,

Gazing at thy holy face

Gentle Mary, Queen of Grace.

Thou who knowest what I seek,

Ere I unlock my lips to speak,

For I am thine in every part

And thou knowest what my heart,

Yearning in my fervid breast,

Ere it be aloud confessed,

Longeth for exceedingly,

Mamma cara, pity me!

By the dearth of childlorn years,

By thy mother Anna’s tears,

By the cry of Joachim,

When the radiant seraphim,

Girdled with eternal light,

Blazed upon the patriarch’s sight

With the joyous heraldry

Of thy sinless infancy.

By the bridal of the Dove,

By thy God’s ecstatic love,

By the home of Nazareth,

When the supernatural breath

Of God enfolded thee, and cried:

“Open to me, love, my bride,

Come to where the south winds blow,

Whence the mystic spices flow,

Calamus and cinnamon,

Living streams from Lebanon.

Fresh flowers upon the earth appear

The time of singing birds is near,

The turtle-dove calls on his mate,

The fruit is fragrant at our gate.

Thy lips are as sweet-smelling myrrh,

When the odorous breezes stir

Amid the garden of the kings;

As incense burns at thanksgivings.

Thy lips are as a scarlet thread,

Like Carmèl is they comely head,

Thou art all mine, until the day

Break, and the shadows flee away!”

Mother, by thy agony

‘Neath the rood of Calvary,

When the over-piteous dole

Pierced through thy very soul

With a sevenfold bitter sword

According to the prophet’s word.

By the sweat and spiny caul,

By the acrid drink of gall,

By the aloes and the tomb,

By thy more than martyrdom,

Dolorosa, give to me

The thing I lowly crave of thee.

By thy glory far above,

Mother, Queen of heavenly love,

By thy crown and royal state,

By thy Heart Immaculate,

Consort of the Deity,

Withouten whose sweet assent He

May nothing deign to do or move

Bound by ever hungered love,

God obedient to thee!

Mother, greatly condescending,

To thy humblest suitor bending,

From thy star-y-pathen throne,

Since it never hath been known

Whoso to this picture hied,

Whoso prayed thee was denied,

Mamma bella, give to me,

The boon I supplicate of thee!

In Santa Chiara, Napoli.

“Madonna and Child,” Carlo Crivelli, c. 1480 (Source)