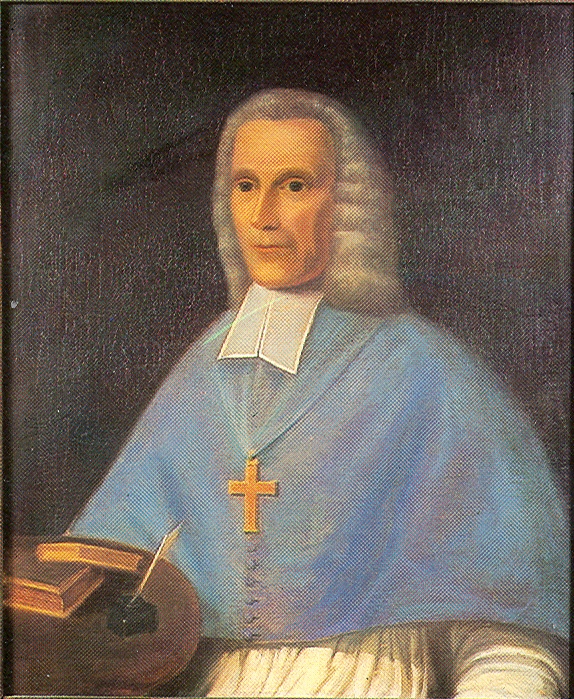

Vera Effigies Augustini Calmet Abbatis Senonensis. (Source).

I was recently asked by the administrator of Catholics from the Crypt to write a brief introduction to Dom Augustin Calmet, Abbot-General of the Congregation of St. Vanne. My qualifications for this task are minimal but, I think, sufficient. First, I know a little about Calmet, which is, sadly, more than many can say. He is an unfairly overlooked figure in our religious and cultural landscape. Secondly, I hope to write my Master’s Thesis on Calmet’s Histoire Universelle, though of course the actual process of research might change my direction. For the time being, I am glad of the challenge, and will likely turn this into the first of a series of short biographies of weird religious figures.

Dom Calmet, born on the 26th of February, 1672, in the then-Duchy of Bar (now Lorraine, France) had a long and impressive career. Entering religious life at the Benedictine Priory of Breuil, he moved around over the years to obtain his education at various abbeys. His itinerary reads like an honor roll of some of the finest establishments of the Franco-German monastic intelligentsia: St. Mansuy, St. Èvre, Munster, Mouyenmoutier, Lay-Saint-Christophe, St. Leopold. Yet the two monasteries most closely associated with his career are Senones Saint-Pierre and Vosges, where he eventually died a holy death.

He achieved widespread scholarly respect for his work in three different fields. First, Calmet distinguished himself as an Exegete. His Biblical method differed from more classical forms of exegesis by focusing entirely on the literal meaning of the text; this exposed him to criticism, even amidst the general acclaim which the book and its abridgements garnered.

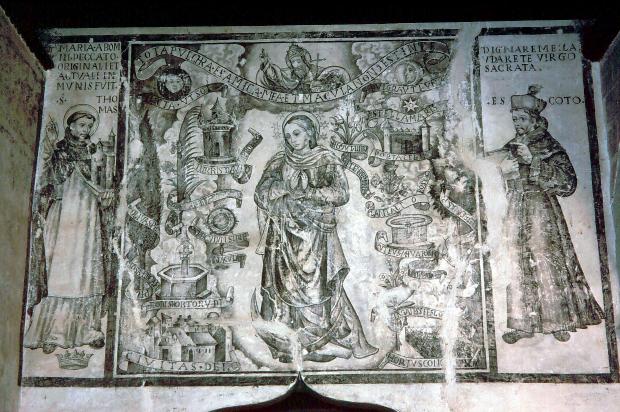

Title page of Book I of his most famous work on Vampires. (Source).

Second, he became an eminent author of sacred and profane history. While my own interest lies most heavily with his Histoire Universelle (1735-47), Calmet also devoted considerable attention to more specific topics. It should come as no surprise, given the libraries to which he had access, that he devoted special care to the region which bore him. His titles include History of the Famous Men of Lorraine (1750), Dissertation on the Highways of Lorraine (1727), Genealogical History of the House of Châtelet (1741), and posthumous histories of both Senones (1877-81) and Munster (1882).

However, Calmet achieved lasting fame for his extremely popular work on Vampires: first, Dissertations on the Apparitions of Angels, Demons, and Spirits, and on the Revenants and Vampires of Hungary, Bohemia, Moravia, and Silesia (1746) He later expanded the text into his famous Treatise on the Apparitions of Spirits and on the Vampires or Revenants of Hungary, of Moravia, &c. in 1752. These texts were, to the best of my knowledge, the first attempt to apply scientific rigor to the tales of the undead then current throughout Europe.

The books were a huge hit, and remain widely respected by occult writers today. To quote one source:

Re-released in 1748, with the most complete edition in 1751, this book is considered to be [the] authoritative treatment on the subject, containing an unprecedented collection of ghostly stories of revenants. It was a best seller for the period, quickly translated into German and Italian for a broader audience. Calmet’s tone considers the possibility of vampires with a certain ambiguity, possibly in light of the larger body of his publications for the church. Still, this is widely regarded as the starting point of all vampiric literature.

The work garnered critical attention from no less a figure than Voltaire. As that eminent source, Wikipedia, relates, Voltaire wrote of Calmet with no small astonishment:

What! It is in our 18th century that there have been vampires! It is after the reign of Locke, of Shaftesbury, of Trenchard, of Collins; it is under the reign of d’Alembert, of Diderot, of Saint-Lambert, of Duclos that one has believed in vampires, and that the Reverend Priest Dom Augustin Calmet, priest, Benedictine of the Congregation of Saint-Vannes and Saint-Hydulphe, abbot of Senones, an abbey of a hundred thousand livres of rent, neighbor of two other abbeys of the same revenue, has printed and re-printed the History of Vampires, with the approbation of the Sorbonne, signed by Marcilli!

[NB: translation is my own]

We can only imagine what conversation transpired between the two thinkers when Voltaire stayed at Senones in 1754, only a few years before the abbot’s death.

It is perhaps unusual that a monk who was, by all accounts, part of the same intellectual circles as the Maurist Enlighteners and the Philosophes would take to such a strange subject. Calmet certainly saw himself as partaking of that wider project. He writes in his preface to the Treatise,

My goal is not at all to foment superstition, nor to maintain the vain curiosity of Visionaries, and of those who believe without examination all that one tells them, as soon as they find therein the marvelous and the supernatural. I do not write but for those reasonable and unprejudiced spirits, who examine things seriously and with sang-froid; I do not speak but for those who do not give their consent to known truths but with maturity, who know to doubt things uncertain, to suspend their judgment in things doubtful, and to refute that which is manifestly false. (Calmet ii).

[NB: translation is my own]

Perhaps we should not be so surprised. After all, the religious history of Europe is peppered with eccentric and erudite men drawn to esoteric studies. And by the time that Dom Calmet died in 1757, the French monastics had not yet reached the height of their oddity. That would come later, with the well-traveled and thoroughly bizarre Swedenborgian and Martinist monk Antoine-Joseph Pernety, whom I hope to someday investigate more thoroughly.

The Revolution changed all that. No longer could monks live their lives freely, let alone attempt serious academic inquiry. It would take the genius of men like Dom Prosper Guéranger to restore the French Benedictines to their former glory.

Senones Abbey today. The monastery was dissolved by Revolutionary forces in 1793, then later sold off as State Property and converted into a textile mill. This desecration continued until 1993, when what was left of the abbey became a Monument historique. (Source).