Montague Summers in clerical garb. (Source)

The history of the Church is a history of odd birds, but it is harder to find odder birds than those which inhabited the British Isles in the fruitful years of the Catholic Revival. The eccentricities of certain English clergy are well-known and well-beloved. One of the great flowers of this tendency was Montague Summers.

A flying devil. (Source)

Augustus Montague Summers was born in Bristol, the youngest of seven. Eventually he went on to study at Trinity College, Oxford, with the intent of seeking ordination in the Church of England. After some time at Lichfield Theological College, he was eventually deaconed and spent his curacy in Bath and the Bristol area. Even at this young stage, he garnered a reputation for eccentricity. In Ellis Hansen’s Decadent Catholicism, we learn the rather delicious fact that at seminary, “he was known to burn incense in his rooms and to wear purple silk socks during Lent” (qtd. by the Modern Medievalist).

This was as far as he made it in the ranks of the C of E, however. As the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography tersely puts it, “Rumours of studies in Satanism and a charge of pederasty, of which he was acquitted, terminated this phase of his career.” The latter charge may have had some truth to it. About this same time, he published a book of Uranian verse entitled Antinous and Other Poems (1907). His interest in pederastic and homosexual themes continued throughout his life. In 1940, he wrote a play about Edward II. Even more scandalously, “Despite his conservative religiosity, Summers was an active member of the British Society for the Study of Sex Psychology, to which he contributed an essay on the Marquis de Sade” (Source 1 and Source 2).

In 1907, though, Summers was out of a job. His hopes of becoming an Anglican clergyman seemed to have been quashed. But as they say, when the Lord closes one door, He opens another. We might imagine that Summers had something like this in mind when, two years later, he converted to Roman Catholicism. He also spent some time on the continent, allegedly for reasons relating to his health. Some have speculated that he might have received valid, if illicit, orders during this sojourn; others have said he spent his time exploring the black arts (vide the Modern Medievalist). We have almost nothing on which to base our speculations.

Now we see him coming to the full bloom of his later, famous eccentricity. It is in this formative period that he lays the foundation for the vivid persona that would make him such a cult literary and religious figure. I will quote the Oxford DNB at length:

On 19 July 1909 Summers was received into the Church of Rome and was granted the clerical tonsure on 28 December 1910; after this his clerical career became murky and remains so. He may have received minor orders as a deacon, but no record of his ordination has ever been found. During his lifetime, he was addressed as the Revd Montague Summers, celebrated mass in his own chapel and those of friends, adopted two names in religion, and invariably wore the dress pertaining to Roman priesthood; his appearance in soutane, buckled shoes, and shovel hat, later with an umbrella of the Sairey Gamp order, was familiar in London and Oxford. He became increasingly eccentric and was described as combining a manifest benignity with a whiff of the Widow Twankey. Some spoke of an aura of evil. It was charitably assumed by his friends that he was indeed a priest, and his devotion was never in question; his biographer Joseph Jerome (Father Broccard Sewell) records that all his life Summers wore the Carmelite scapular.

On a side-note, Fr. Brocard Sewell was a deeply strange man himself. But I digress.

If Summers—or, as he was now calling himself, “Reverend Alphonsus Joseph-Mary Augustus Montague Summers”–had simply remained a slightly dubious cleric, we probably wouldn’t remember him. He might have become a little more than a footnote in the history of the Episcopi Vagantes so famous for dispensing illicit orders here and there. But he did not. Instead, he wrote. Prolifically.

Summers started off with genuine and important literary scholarship. Eventually, he even became a member of the Royal Society of Literature. He had certainly earned it with the sweat of his brow. He produced fairly good books on Restoration Drama, including major editions of previously neglected playwrights such as Aphra Behn. In this capacity, he had some connections with the world of the British stage; he was a founder of the Phoenix Theatre. He wrote an important monograph on Shakespeare. In another work he also proved that the terrible Gothic novels that Jane Austen mentions in Northanger Abbey were all real books. Gothic literature remained a lifelong passion, in part because it dovetailed so well with his overriding obsession—the occult.

Montague Summers in clerical collar. (Source)

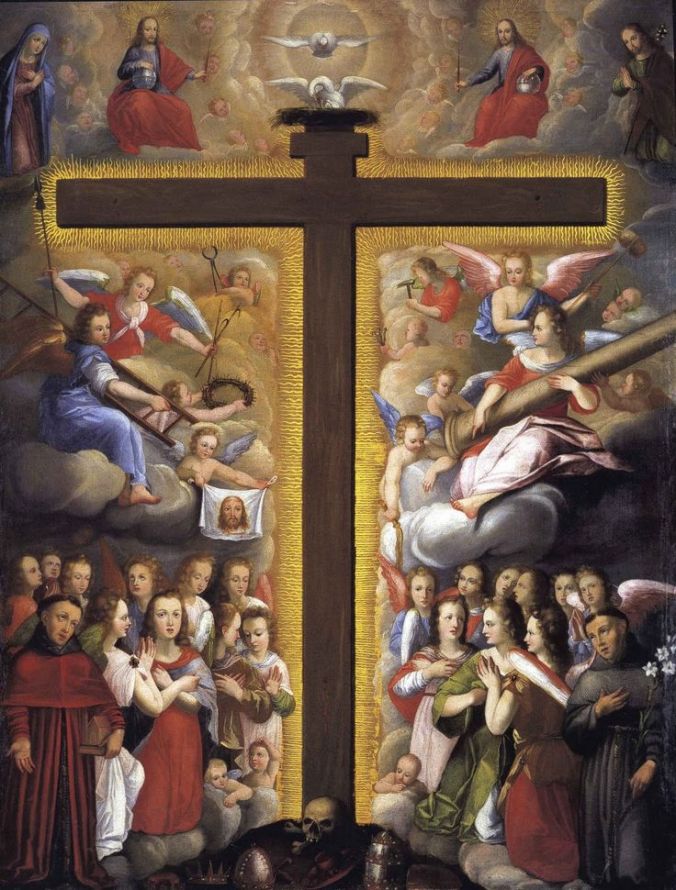

Summers is most famous today for his several books on witches, demons, vampires, ghosts, and other supernatural phenomena. He translated and edited the first English edition of the Malleus Maleficarum, that great tome of Medieval witch-hunting. He did the same with several other demonological manuals: The Demonality of Sinistrari, The Discovery of Witches by Hopkins, the Compendium Maleficarum of Guazzo, and the Demonolatry of Nicolas Remy. He wrote a text on The Physical Phenomena of Mysticism, in contrast with his somewhat headier and less decadent contemporary, Evelyn Underhill. He edited more than one collection of horror stories. He wrote three seminal texts on vampirism, one on lycanthropy, and four on various aspects of witchcraft. Following the best scholarship of the day, Summers endorsed the idea of the “Witch-Cult,” long suppressed by Christianity but operating sub rosa in Europe down the centuries (this hypothesis has long since been undermined by scholars across disciplines). He would often draw upon a huge range of historical, theological, ethnographic, and literary sources in constructing his arguments. All of his texts speak to his vast learning. It is probable that upon his death, Montague Summers knew more about the history and practice of the occult than any other Englishman then living.

The Modern Medievalist has preserved some charming anecdotes of the later, esoteric Summers over on his blog. We read, for example, the following passage from Ellis Hansen’s Decadent Catholicism:

…although Summers was a brilliant conversationalist, he had always a thick carapace of artificiality in his demeanor, a kind of mask that recalled the studied falsity of the classic dandy, not to mention the distrustful reserve of Walter Pater and John Gray. His style was decidedly aristocratic, Continental, and decadent, with the inevitable intimation of sexual impropriety. His friend writes of him, “He would often meet me with such an expression as Che! Che!, accompanied by a conspiratorial smile; or he would look closely at me and murmur, ‘Tell me strange things’.”

Or this remarkable scene drawn for us by Fr. Brocard Sewell:

Summers…could often have been seen entering or leaving the reading room of the British Museum, carrying a large black portfolio bearing on its side a white label, showing in blood-red capitals, the legend “VAMPIRES.”

Not to mention the fact that Summers went about town with a cane topped by a depiction of Leda and the Swan (vide the Modern Medievalist).

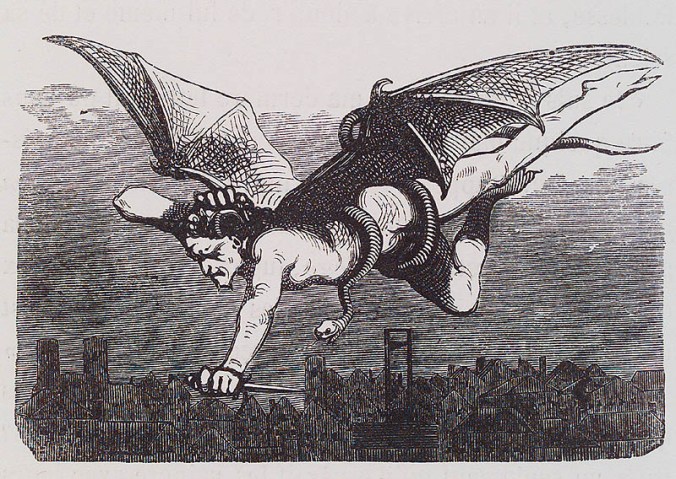

A caricature of Summers from the Evening Standard, probably from 1925. (Source).

What distinguished Summers’ writing on these dark subjects is the absolute credulity with which he approaches his subject. Unlike his predecessor, Dom Calmet, who wrote about ghosts with ambivalence and vampires with manifest doubt, Summers did not hesitate to express his firm certainty about both (and much more). He believed in all the phenomena he wrote about—the whole ghastly parade of incubi and succubi, of witches dancing at the Sabbath, of vampires rising from the grave to seek the blood of the living, of werewolves stalking innocent Christians in the night. Everything that belonged to the netherworld was as real to him as the people you or I might meet in the street. His purple prose often slips into breathless passages of scholarly terror. Observe the following lines from Chapter Two of The Vampire: His Kith and Kin:

It has been said that a saint is a person who always cho[o]ses the better of the two courses open to him at every step. And so the man who is truly wicked is he who deliberately always cho[o]ses the worse of the two courses. Even when he does things which would be considered right he always does them for some bad reason. To identify oneself in this way with any given course requires intense concentration and an iron strength of will, and it is such persons who become vampires.

The vampire is believed to be one who has devoted himself during his life to the practice of Black Magic, and it is hardly to be supposed that such persons would rest undisturbed, while it is easy to believe that their malevolence had set in action forces which might prove powerful for terror and destruction even when they were in their graves. It was sometimes said, but the belief is rare, that the Vampire was the offspring of a witch and the devil.

Summers also stood apart from his thoroughly modern era in endorsing “Church-sanctioned methods of destroying” the monsters he wrote about (The Modern Medievalist).

And although his pages are littered with authoritative quotes from long-dead writers, Summers was not unaware of the dark streams that swirled about him in his own day. Richard Cavendish reports in a typically mordant passage from The Black Arts (1967) how Summers treated the claims of the twentieth century’s greatest occultist, Aleister Crowley:

Aleister Crowley could not pass over such an opportunity to scandalize his readers. ‘For the highest spiritual working one must accordingly choose that victim which contains the greatest and purest force. A male child of perfect innocence and high intelligence is the most satisfactory and suitable victim.’ Montague Summers took this seriously, as he took everything else, and quotes it with gratified horror, in spite of Crowley’s footnote in which he says that he performed this sacrifice an average of 150 times a year between 1912 and 1928! (Cavendish 238)

In spite of it all, Summers remained well-liked in certain circles. He moved among the literary elite of his own day, an eccentric among eccentrics. One of his friends, the actress Dame Sybil Thorndike, relates something of his personality:

I think that because of his profound belief in the tenets of orthodox Catholic Christianity he was able to be in a way almost frivolous in his approach to certain macabre heterodoxies. His humour, his “wicked humour” as some people called it, was most refreshing, so different from the tiresome sentimentalism of so many convinced believers.

His caricature in the Evening Standard captures something of this impish quality.

But although he was known and appreciated in his own day, he has been largely forgotten in the intervening decades. There have not been many books about Montague Summers, and he is not widely read. However, that will soon hopefully change. In recent years, Georgetown University has acquired Summers’ papers, once thought irrevocably lost. Fittingly, they have a peculiar provenance, having been “discovered languishing in an old farmhouse in Manitoba.” The story of how they got there is probably as strange as any of Summers’ own books. Georgetown’s collection has made possible a forthcoming biography by Matthew Walther that will hopefully rectify the longstanding neglect of this bizarre yet sincere writer.

But perhaps a question rises. Not every obscure author is worth reviving. Why bother with Montague Summers? A man of outdated style, of dubious subjects, and of very questionable morals to boot…what does he offer the modern reader?

The grave of Montague Summers. (Source)

The Modern Medievalist has a few thoughts on the matter.

Montague Summers is, at best, a good fit for the Institute of Christ the King and a throwback to an age when priests were also arbiters, makers, and preservers of high culture a la Antonio Vivaldi; at worst, a “daughter of Trent” who, if he ever actually was a priest to begin with, wasted his vocation on trivialities rather than the cure of souls.

Perhaps. I am not so convinced that Summers would have fit in any age. He was a decadent, and a great deal of decadence is contrarianism. Though the comparison with ICKSP is hilarious.

I think the message of Summers’s life and work can best be summed up in his epitaph. On the black stone hat marks his grave in Richmond Cemetery, we read a simple phrase; “Tell me strange things.” These four words that he used to say to his friends encompass his whole life, packed as it was with “strange things.” Summers matters today not because he is a towering figure of literary talent, nor because his scholarly subjects are of vital importance, nor because he is a moral exemplar of impeccable religiosity. He matters because he can remind us to embrace the mystery of life. As we read in one of those plays that Summers so loved, “There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio,/Than are dreamt of in your philosophy.” Summers lived by those words. The more I learn about the world, the more reason I see in them. And what better day to remember this humbling, bewildering, frightful truth than on All Hallows’ Eve?