A while back I produced a short post entitled “A View of the Sacraments in the Age of Enlightenment.” Here I give you another series of similar images, this time from the hand of Giuseppe Maria Crespi, also known as “Lo Spagnuolo.” These paintings from 1712, so reminiscent of Rembrandt, hang in the Gemäldegalerie, Dresden. Originally commissioned by Cardinal Pietro Ottoboni, that towering figure of late Baroque culture, they passed posthumously up to Germany, where they made their way into collection of the Elector of Saxony.

Let me begin by saying that, as with the information in the above paragraph, all of the images can be found at Wikipedia.

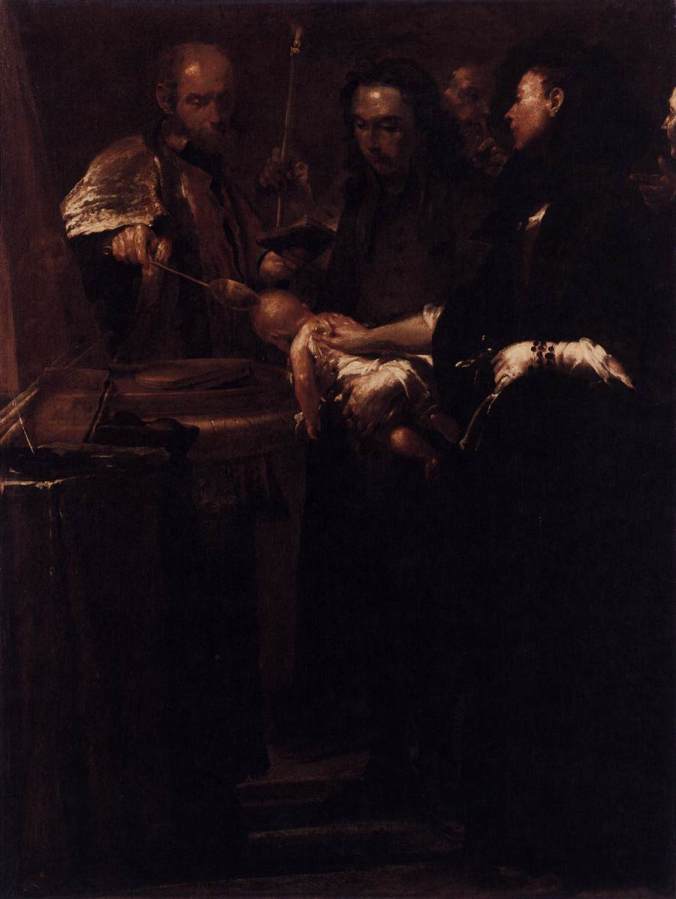

“Baptism.” Crespi’s sparing use of light demonstrates the central conjunction of the scene. Allowing our eyes to wander along the central line of illumination, we follow the arm of the priest pouring water on the head of the outstretched infant to the mother’s rosary-wrapped wrist just beyond. I am convinced that the use of light in all of these images is the key to their meaning. Crespi uses light to illustrate the work of sacramental grace, and darkness to emphasize the mortality, evanescence, and weariness of our ordinary world. “The people in darkness have seen a great light” – thus spake Isaiah.

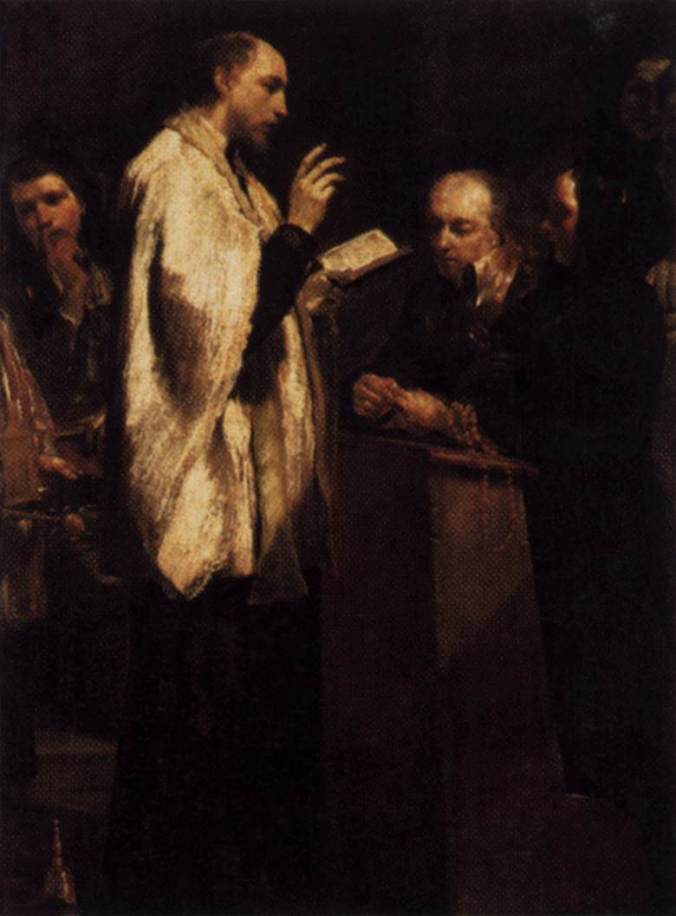

“Communion.” The priest’s face is shrouded in darkness, and rightly so. It is not he who offers the bread of life, but Christ in him. Interesting collar, too. Sure looks familiar. Cardinal Ottoboni was patron of the Congregation of the Oratory at Rome for some time, and it’s entirely possible that Crespi would have taken the Oratorians as his model here. Besides that, the setting of the scene is strikingly barren. Crespi’s choice to leave out the probable altar rail lends the scene an intimacy that captures the very heart of the worship here portrayed.

“Confirmation.” Crespi’s lightest and most colorful piece in the series. The vivid red-orange of the boy’s robes call to mind the tongues of flame that appeared on Pentecost, as does the (relatively) diffuse light bathing the scene. The brightest part of the image is the Bishop’s arm, only just anointing the boy’s head. The strong predominance of vertical and diagonal lines in this piece only reinforce the sense of descent. Like all the paintings, the scene here is crowded without being cramped. Crespi seems to have penetrated to the deeply ecclesial nature of the sacraments. The sacraments are what give the Christian community its underlying spiritual cohesion and form. To quote De Lubac, “The Eucharist makes the Church.”

“Confession.” Quite in contrast to “Confirmation,” we come to Crespi’s darkest piece in the series. The overwhelming color is black. Confession is the sacrament that deals most straightforwardly with the reality of sin. The narrow contraction of the light – it comes only from one side, and very weakly. The formal likeness between confessor and penitent reminds us of the condition of sin common to all men. This painting is also the only one in the series where we don’t see a crowd. Only two figures are visible. In the end, we are always “alone with the Alone.”

“Matrimony.” Perhaps the most human of Crespi’s scenes. But we find unusual notes, things I can’t quite interpret with satisfaction. For a painting of matrimony, we hardly see the couple. Indeed, the bride has almost been swallowed up by the shadows. Nigra sum sed formosa. Perhaps. The priest stands like a pillar of cloud before them, blessing their union. That seems straightforward enough. Yet why is the man on the left holding his hand to his mouth, as if to signal silence? Perhaps because the matter of this sacrament is always properly taken in secret…

“Ordination.” This composition is a swirling mix of blacks, browns, subtle golds, and occasionally, whites. The point that stands out most is the break in this overall scheme – the youthful, rosy visage of the ordinand, coupled with the slightly ruddy shadows that fall across his hand. What a contrast with the other figures, all of whom are shrouded in darkness and invested with a manifest pallor. Here is an image of youth, a prospect of renewal against a backdrop of dignified decay.

“Extreme Unction.” At last we come to the end, the place of the skull. It is only fitting that Crespi should choose to depict a collection of Franciscans for this sacrament. Religious life is always a preparation for death. Yet the bright patch of light improbably illuminating the shoulder of the attendant friar contrasts starkly with the shadowy body of the dying father and points to new hope.