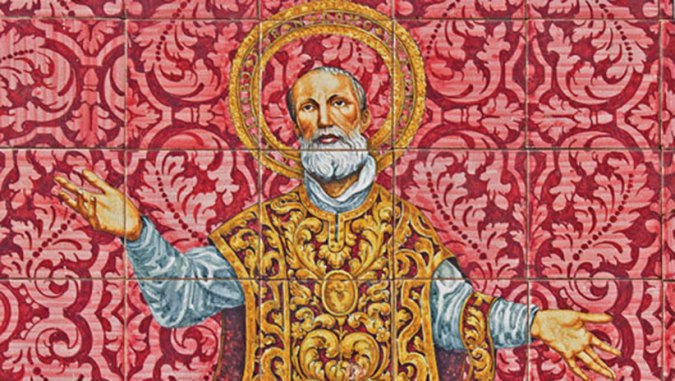

Articles of devotion to St. Philip Neri, Florence. Photo taken by the author in June of 2015.

St. Philip Neri is my favorite saint. I came to his acquaintance during the summer after my second year in college, when I studied abroad in locations marked by the presence of Oratories. I believe that I was, so to speak, “introduced” to St. Philip by his famous son, the Blessed Cardinal Newman, whose work I had already read and admired. It is also perhaps of some significance that I had devoted that year of my Catholic life to the Holy Spirit. Desiring a deeper friendship with St. Philip, I followed along with Newman’s novena to St. Philip last May. Having read several biographies and having started a blog, I thought I might try my own hand at offering some small act of devotion to St. Philip in the form of nine brief meditations on his life and virtues.

Unfortunately, it seems that the frenzy of graduation week has crept up on me, and I was unable to complete this task. I do, however, offer my own biography of the saint. My sources are chiefly the various Oratorian materials produced by the London and Oxford houses, Good Philip, by Alfonso Cardinal Capecelatro, the biographies by V.J. Matthews, Louis Bouyer, Anne Hope, and Theodore Maynard, and finally, sundry writings by Cardinal Newman, Fr. Faber, Fr. Jonathan Robinson, and Monsignor Knox. All are excellent resources, and I would be happy to provide more details about them in the comments section if asked.

The actual text of the novena will be taken from the Newman Reader, which is my go-to source for all things Newman. I claim no authorship of these texts and am entirely in debt to that great theologian, the Blessed Cardinal of the Birmingham Oratory. I have decided to do this, rather than simply link to the Newman Reader, in part because I am starting my novena a day later than Newman does. Newman began his novena to St. Philip on the 17th and ended it on the 25th, presumably because of the various festivities that the 26th would usher in. However, as I do not live in an Oratory, I will be starting and ending a day later, so that the readings of the ninth day fall on the feast proper. There is a certain liturgical grace that comes with the feast this year, but I will discuss that in another post.

John Henry Newman as an Oratorian. (Source)

For now, I’ll say that I will be offering this novena for the vocation of X.

St. Philip, as we shall see, is a very good heavenly guide for young men. He is especially helpful for those who are trying to discern the will of God in their lives.

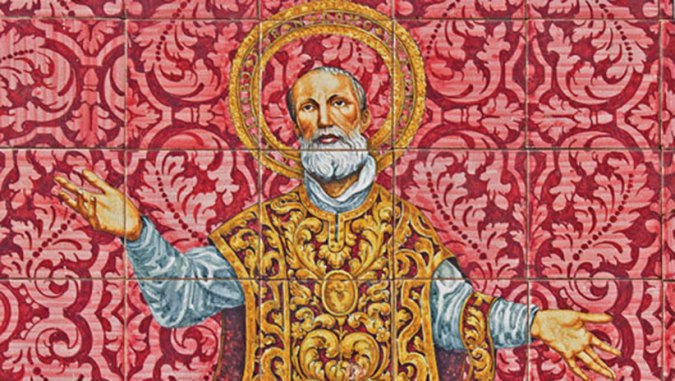

A famous image of St. Philip. He is customarily depicted in a red or rose chasuble in iconography. (Source).

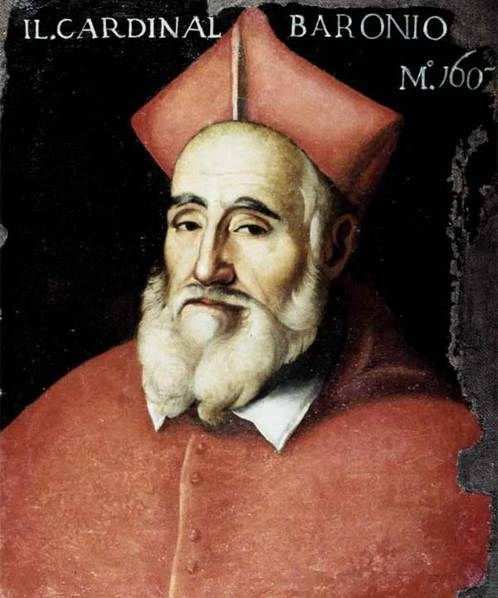

Each day, start by reading the meditation and prayer, and then say the prayer of Cardinal Baronius:

Look down from heaven, Holy Father, from the loftiness of that mountain to the lowliness of this valley; from that harbour of quietness and tranquillity to this calamitous sea. And now that the darkness of this world hinders no more those benignant eyes of thine from looking clearly into all things, look down and visit, O most diligent keeper, this vineyard which thy right hand planted with so much labour, anxiety and peril. To thee then we fly; from thee we seek for aid; to thee we give our whole selves unreservedly. Thee we adopt as our patron and defender; undertake the cause of our salvation, protect thy clients. To thee we appeal as our leader; rule thine army fighting against the assaults of the devil. To thee, kindest of pilots, we give up the rudder of our lives; steer this little ship of thine, and, placed as thou art on high, keep us off all the rocks of evil desires, that with thee for our pilot and guide, we may safely come to the port of eternal bliss. Amen.

Those of you who prefer Latin can find it at this link.

On the ninth day, conclude by adding on the Collect and Litany at the very end of this post.

St. Philip’s Life

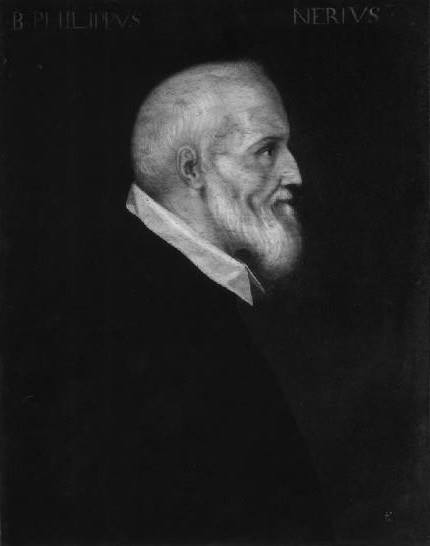

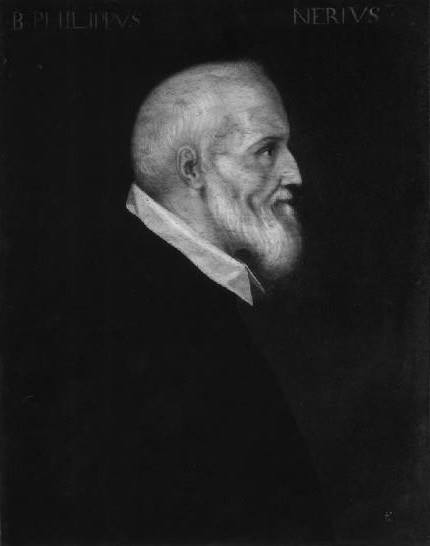

Saint Philip Neri (1515-1595), by Carlo Dolci, c. 1645. The finest portrait of the saint was painted long after he died. In his own life, St. Philip was patron of the arts, and was even Palestrina’s confessor. (Image Source).

St. Philip Romolo Neri was born in Florence to a loving father and stepmother and brought up in the faith by the Dominicans of San Marco. The embers of Savonarola’s fiery spirit still burned in the memories of the Florentines, and for the rest of his life, St. Philip would hold the reformer in a high regard. But his temperament was as different from Savonarola’s as day is from night. St. Philip was always good-natured, kind, and generous. He was not overly pious, with play-acting the Mass or anything of that sort. Instead, he cultivated a winning personality that earned him the nickname “Pippo Buono.” He was remarkably humble, never giving much weight to the things of this world. Once, he was shown a beautiful diagram of his family tree; he promptly tore it up.

When he reached adulthood, St. Philip went to seek his fortune with his uncle Romolo, a merchant in San Germano. He found that the life of commerce was not conducive to his temperament, and so, after praying at the shrines of the Benedictines at Monte Cassino and Gaeta, he left for Rome almost penniless. The city had just been sacked by the soldiers of the Emperor, and work was hard to come by. Nevertheless, St. Philip was soon employed as a tutor for the Caccia family. The boys he taught would later go on to lives of holiness as priests. St. Philip made few friends in this period of his life. Like a hermit, he would hardly eat anything and spent his nights in the catacombs, remembering and praying to the martyrs of the early Church. On one such occasion, while he was in the catacombs of San Sebastiano, he had a mystical experience that would forever change his life. The Holy Spirit descended into his heart as a ball of fire. For the rest of his life, he would report heart palpitations, an incredible heat, and physical shaking – sometimes enough to move the chair in which he sat. Upon occasion, it was enough to convert a sinner only to draw their head to his Spirit-infused breast. Only in very old age did he confide his secret. When he died, his heart was found to be considerably enlarged. Several ribs were dislocated by its growth.

But in youth, he kept all this under wraps. He slowly started to gain a following. He would frequent the Seven Stational Churches, even leading bands of pilgrims on picnics. As he got older, these journeys grew in size and festivity. But in the early days, he was followed only by a few young men who were attracted to a charismatic tutor. He would also visit and help in the hospitals, perhaps the most common form of charitable work in Renaissance Italy. He would later exert a great influence on that marvelous saint of the hospitals, St. Camillus of Lellis.

St. Philip and his friends moved into the Church of San Girolamo, where, every afternoon, they would have a time of prayer, hymn-singing, recitation of the Bible, public commentary on the Scriptures, and some lesson from the history of the Church or the lives of the saints. This was the first Oratory. St. Philip’s way of life looked mighty suspicious to the authorities in a Rome still reeling from the Reformation, and he was investigated and opposed by several figures – namely an irate cardinal close to the Pope. But that cardinal died before the end of his investigation into St. Philip, an event whispered to be the wrath of God. Every other opposition fell away, and in time, St. Philip became an established figure in Rome. He was eventually persuaded to seek ordination. While never a Doctor of the Church, St. Philip learned his theology well, and was able to put it to good use in his later pastoral life.

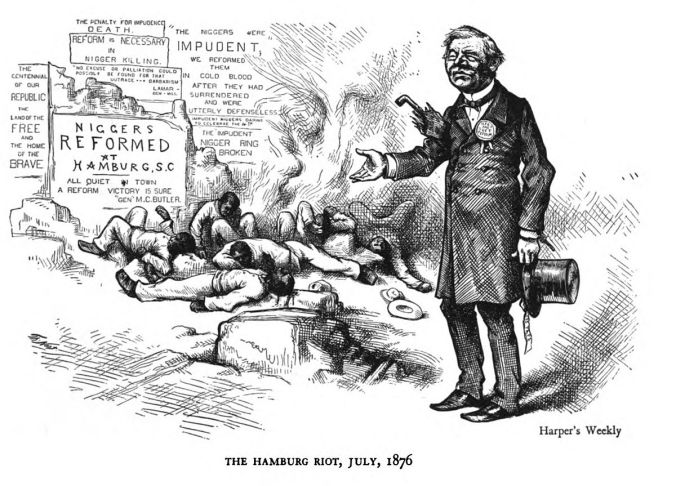

When the Church of the St. John of the Florentines requested that St. Philip move to their community, he balked. Instead, he sent some of his best disciples, including Cesare Baronius, later to become a great cardinal and historian of the Church. However, all of the priests he sent were required to return to San Girolamo every day for the Oratory sessions. In this practice, we can perceive the seeds of the Congregation that would later flourish throughout the Catholic world.

The Chiesa Nuova, Rome. (Source)

When St. Philip was given the chance to build a new church, Santa Maria in Vallicella, he stunned the architects by boldly demanding a much larger structure than expected. Yet build it he did, and the “Chiesa Nuova,” or “New Church,” became the nerve center for the entire Oratorian family. St. Philip always resisted turning the Oratory into a religious order; today, it is still no such thing. Oratorians take no vows, but are bound to each other by a promise of charity. Love (and, one must assume, a tremendous amount of patience) holds each Oratory together. The closest parallel would be the Benedictines, who live in one place their entire life and belong to a wide, loose, familial confederation.

St. Philip Neri made friends with a great many Romans, and more than a few saints. He was on close terms with many of the Popes of his day, and more than one went to him for confession. Two great cardinals came from his immediate circle, Baronius the historian and Tarugi the politician. St. Philip was particularly intimate with the great Capuchin mystic, St. Felix of Cantalice. He also sent so many men to the Jesuits that St. Ignatius took to calling him “the Bell of the Society,” always bringing in more, but never entering himself. All in all, it was for the best. St. Philip’s temperament and spirituality were thoroughly un-Jesuit. Where St. Ignatius was hard, St. Philip was soft; where St. Ignatius was demanding, St. Philip was persuasive; where St. Ignatius sent his sons to a thousand works, St. Philip allowed them but one. But the two saints always held each other in a high, slightly bemused regard. St. Philip was the confessor of St. Camillus of Lellis as well as the composers Palestrina and Animuccia. Their compositions for St. Philip’s afternoon meetings became the first oratorios. St. Philip was always trying to draw souls to Christ by way of holy beauty. This quality, along with so many others, would make him a particularly apt spiritual father for the revival of Catholicism in 19th century Britain.

St. Philip could be a very hard confessor. He could tell if someone was holding back a sin, and he’d often relate the substance of that sin to the penitent himself. Yet his demands were always tempered by a certain tenderness. He was never inclined to endorse any kind of extreme asceticism, and positively distrusted anyone who claimed special visions and ecstasies.

Nevertheless, the Lord did grant him many such graces anyway—and usually when saying Mass. St. Philip was a mystic of the Eucharist. Just in order to get through the process of vesting, let alone the Mass itself, he would have his server read jokes to him in the sacristy. In his old age, he would go into ecstasies at the Masses he celebrated, sometimes taking a few hours to say the entire liturgy. He also popularized the devotion of the Forty Hours of Adoration, a tradition that still takes place in so many of the Oratories of the world.

St. Philip was known as a joker, and he would teach his disciples to mortify their reason through his many practical jokes. Along with the Laudi of Jacopone da Todi, the joke books then popular in Florence and Rome were some of his favorite reading. He once showed up to a formal function with half of his beard shaved off. At another solemn occasion, he started to stroke the beard of a Swiss guard for no apparent cause. At yet another time, he made his aristocratic disciple Tarugi follow and carry a little lapdog through the city, to the jeers of the crowds. He is known as the “Joyful Saint” for very good reasons.

He effected such a change in the devotions and morals of the broken, decadent, and dispirited city, that he became known as the Third Apostle of Rome. When he died, he was immediately the subject of widespread devotion. The official workings of the Vatican could not proceed quickly enough for the people of Rome, who prayed to the departed priest with all the zeal they could muster. When he was finally elevated to sainthood in 1622, the Romans took to saying that the Pope had canonized “four Spaniards and a saint.”

Yet Spain would not receive the Florentine’s spiritual heritage in its fullness. Nor would France, where Cardinal de Bérulle heard of the Oratory, liked the idea, and started his own order with a very different organization and spirituality. The French Oratorians may be considered St. Philip’s nephews, but not his sons. For many centuries, only Italy bore the mark of what St. Philip really wanted from his sons – holy, independent houses of secular priests bound together by nothing more than the bond of charity.

And the Italian Oratories persevered valiantly until a convert from Anglicanism came to Rome to study for the priesthood: John Henry Newman. It was Newman, along with Fr. Frederick William Faber and Fr. Ambrose St. John, who brought the Oratory to England, where it thrived as almost nowhere else. The Oratories of Birmingham and London were the great centers of English Catholicism, leavening all the other efforts of the Church in that land. Oratorians played a significant role in the lives of Gerard Manley Hopkins, Oscar Wilde, and J.R.R. Tolkien, to mention but a few. The Oratory has seen an explosion in the United Kingdom over the last few decades, with new houses in Oxford, York, Manchester, Cardiff, and Bournemouth having opened or set to open in the near future. It seems that in these troubled times, the Holy Spirit is multiplying their numbers for some great work. More and more Oratories are starting in the United States, many on the lines of the English and Italian models. In Toronto, Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Washington, Kalamazoo, and so many more cities, St. Philip is making his home. In these days of preparation for his feast, let us remember the great works God has wrought through him and his sons.

Day 1: Philip’s Humility

The famous effigy of St. Philip in the Roman Oratory, made while he was still living. It would go around to the Seven Churches when he could no longer make the pilgrimage. (Source)

If Philip heard of anyone having committed a crime, he would say, “Thank God that I have not done worse.”

At confession he would shed abundance of tears, and say, “I have never done a good action.”

When a penitent showed that she could not bear the rudeness shown towards him by certain persons who were under great obligations to him, he answered her, “If I were humble, God would not send this to me.”

When one of his spiritual children said to him, “Father, I wish to have something of yours for devotion, for I know you are a Saint,” he turned to her with a face full of anger, and broke out into these words: “Begone with you! I am a devil, and not a saint.”

To another who said to him, “Father, a temptation has come to me to think that you are not what the world takes you for,” he made answer: “Be sure of this, that I am a man like my neighbours, and nothing more.”

If he heard of any who had a good opinion of him, he used to say, “O poor me! how many poor girls will be greater in Paradise than I shall be!”

He avoided all marks of honour. He could not bear to receive any signs of respect. When people wished to touch his clothes, and knelt as he passed by, he used to say, “Get up! get out of my way!” He did not like people to kiss his hand; though he sometimes let them do so, lest he should hurt their feelings.

He was an enemy to all rivalry and contention. He always took in good part everything that was said to him. He had a particular dislike of affectation, whether in speaking, or in dressing, or in anything else.

He could not bear two-faced persons; as for liars, he could not endure them, and was continually reminding his spiritual children to avoid them as they would a pestilence.

He always asked advice, even on affairs of minor importance. His constant counsel to his penitents was, that they should not trust in themselves, but always take the advice of others, and get as many prayers as they could.

He took great pleasure in being lightly esteemed, nay, even despised.

He had a most pleasant manner of transacting business with others, great sweetness in conversation, and was full of compassion and consideration.

He had always a dislike to speak of himself. The phrases “I said,” “I did,” were rarely in his mouth. He exhorted others never to make a display of themselves, especially in those things which tended to their credit, whether in earnest or in joke.

As St. John the Evangelist, when old, was continually saying, “Little children, love one another,” so Philip was ever repeating his favourite lesson, “Be humble; think little of yourselves.”

He said that if we did a good work, and another took the credit of it to himself, we ought to rejoice and thank God.

He said no one ought to say, “Oh! I shall not fall, I shall not commit sin,” for it was a clear sign that he would fall. He was greatly displeased with those who made excuses for themselves, and called such persons. “My Lady Eve,” because Eve defended herself instead of being humble.

Prayer

PHILIP, my glorious patron, who didst count as dross the praise, and even the good esteem of men, obtain for me also, from my Lord and Saviour, this fair virtue by thy prayers. How haughty are my thoughts, how contemptuous are my words, how ambitious are my works. Gain for me that low esteem of self with which thou wast gifted; obtain for me a knowledge of my own nothingness, that I may rejoice when I am despised, and ever seek to be great only in the eyes of my God and Judge.

Prayer of Cardinal Baronius (above)

Day 2: Philip’s Devotion

St. Philip had a tender devotion to Our Lady, and she gave him many outstanding graces. (Source).

The inward flame of devotion in Philip was so intense that he sometimes fainted in consequence of it, or was forced to throw himself upon his bed, under the sickness of divine love.

When he was young he sometimes felt this divine fervour so vehemently as to be unable to contain himself, throwing himself as if in agony on the ground and crying out, “No more, Lord, no more.”

What St. Paul says of himself seemed to be fulfilled in Philip: “I am filled with consolation—I over-abound with joy.”

Yet, though he enjoyed sweetnesses, he used to say that he wished to serve God, not out of interest—that is, because there was pleasure in it—but out of pure love, even though he felt no gratification in loving Him.

When he was a layman, he communicated every morning. When he was old, he had frequent ecstacies during his Mass.

Hence it is customary in pictures of Philip to paint him in red vestments, to record his ardent desire to shed his blood for the love of Christ.

He was so devoted to his Lord and Saviour that he was always pronouncing the name of Jesus with unspeakable sweetness. He had also an extraordinary pleasure in saying the Creed, and he was so fond of the “Our Father” that he lingered on each petition in such a way that it seemed as if he never would get through them.

He had such a devotion to the Blessed Sacrament that, when he was ill, he could not sleep till he had communicated.

When he was reading or meditating on the Passion he was seen to turn as pale as ashes, and his eyes filled with tears.

Once when he was ill, they brought him something to drink. He took the glass in his hand, and when he was putting it to his mouth stopped, and began to weep most bitterly. He cried out, “Thou, my Christ, Thou upon the Cross wast thirsty, and they gave Thee nothing but gall and vinegar to drink; and I am in bed, with so many comforts around me, and so many persons to attend to me.”

Yet Philip did not make much account of this warmth and acuteness of feeling; for he said that Emotion was not Devotion, that tears were no sign that a man was in the grace of God, neither must we suppose a man holy merely because he weeps when he speaks of religion.

Philip was so devoted to the Blessed Virgin that he had her name continually in his mouth. He had two ejaculations in her honour. One, “Virgin Mary, Mother of God, pray to Jesus for me.” The other, simply “Virgin Mother,” for he said that in those two words all possible praises of Mary are contained.

He had also a singular devotion to St. Mary Magdalen, on whose vigil he was born, and for the Apostles St. James and St. Philip; also for St. Paul the Apostle, and for St. Thomas of Aquinum, Doctor of the Church.

Prayer

PHILIP, my glorious Patron, gain for me a portion of that gift which thou hadst so abundantly. Alas! thy heart was burning with love; mine is all frozen towards God, and alive only for creatures. I love the world, which can never make me happy; my highest desire is to be well off here below. O my God, when shall I learn to love nothing else but Thee? Gain for me, O Philip, a pure love, a strong love, and an efficacious love, that, loving God here upon earth, I may enjoy the sight of Him, together with thee and all saints, hereafter in heaven.

Prayer of Cardinal Baronius (above)

Day 3: Philip’s Exercise of Prayer

A depiction of St. Philip by the contemporary Italian artist, Salvo Russo. (Source).

From very boyhood the servant of God gave himself up to prayer, until he acquired such a habit of it, that, wherever he was, his mind was always lifted up to heavenly things.

Sometimes he forgot to eat; sometimes, when he was dressing, he left off, being carried away in his thought to heaven, with his eyes open, yet abstracted from all things around him.

It was easier for Philip to think upon God, than for men of the world to think of the world.

If anyone entered his room suddenly, he would most probably find him so rapt in prayer, that, when spoken to, he did not give the right answer, and had to take a turn or two up and down the room before he fully came to himself.

If he gave way to his habit of prayer in the most trifling degree, he immediately became lost in contemplation.

It was necessary to distract him lest this continual stretch of mind should be prejudicial to his health.

Before transacting business, however trivial, he always prayed; when asked a question, he never answered till he had recollected himself.

He began praying when he went to bed, and as soon as he awoke, and he did not usually sleep more than four, or at the most five hours.

Sometimes, if anyone showed that he had observed that Philip went to bed late or rose early in order to pray, he would answer, “Paradise is not made for sluggards.”

He was more than ordinarily intent on prayer at the more solemn feasts, or at a time of urgent spiritual necessities; above all, in Holy Week.

Those who could not make long meditations he advised to lift up their minds repeatedly to God in ejaculatory prayers, as “Jesus, increase my faith,” “Jesus, grant that I may never offend Thee.”

Philip introduced family prayer into many of the principal houses of Rome.

When one of his penitents asked him to teach him how to pray, he answered, “Be humble and obedient, and the Holy Ghost will teach you.”

He had a special devotion for the Third Person of the Blessed Trinity, and daily poured out before Him most fervent prayers for gifts and graces.

Once, when he was passing the night in prayer in the Catacombs, that great miracle took place of the Divine presence of the Holy Ghost descending upon him under the appearance of a ball of fire, entering into his mouth and lodging in his breast, from which time he had a supernatural palpitation of the heart.

He used to say that when our prayers are in the way of being granted, we must not leave off, but pray as fervently as before.

He especially recommended beginners to meditate on the four last things, and used to say that he who does not in his thoughts and fears go down to hell in his lifetime, runs a great risk of going there when he dies.

When he wished to show the necessity of prayer, he said that a man without prayer was an animal without reason.

Many of his disciples improved greatly in this exercise—not religious only, but secular persons, artisans, merchants, physicians, lawyers, and courtiers—and became such men of prayer as to receive extraordinary favours from God.

Prayer

PHILIP, my holy Patron, teach me by thy example, and gain for me by thy intercessions, to seek my Lord and God at all times and in all places, and to live in His presence and in sacred intercourse with Him. As the children of this world look up to rich men or men in station for the favour which they desire, so may I ever lift up my eyes and hands and heart towards heaven, and betake myself to the Source of all good for those goods which I need. As the children of this world converse with their friends and find their pleasure in them, so may I ever hold communion with Saints and Angels, and with the Blessed Virgin, the Mother of my Lord. Pray with me, O Philip, as thou didst pray with thy penitents here below, and then prayer will become sweet to me, as it did to them.

Prayer of Cardinal Baronius (above)

Day 4: Philip’s Purity

St. Philip in tiles. Although I don’t know where this photo was taken, I am reminded of the thriving tradition of decorative tiling in Portugal. (Source).

Philip well knowing the pleasure which God takes in cleanness of heart, had no sooner come to years of discretion, and to the power of distinguishing between good and evil, than he set himself to wage war against the evils and suggestions of his enemy, and never rested till he had gained the victory. Thus, notwithstanding he lived in the world when young, and met with all kinds of persons, he preserved his virginity spotless in those dangerous years of his life.

No word was ever heard from his lips which would offend the most severe modesty, and in his dress, his carriage, and countenance, he manifested the same beautiful virtue.

One day, while he was yet a layman, some profligate persons impudently tempted him to commit sin. When he saw that flight was impossible, he began to speak to them of the hideousness of sin and the awful presence of God. This he did with such manifest distress, such earnestness, and such fervour, that his words pierced their abandoned hearts as a sword, and not only persuaded them to give up their horrible thought, but even reclaimed them from their evil ways.

At another time some bad men, who are accustomed to think no one better than themselves, invited him on some pretext into their house, under the belief that he was not what the world took him to be; and then, having got possession of him, thrust him into a great temptation. Philip, in this strait, finding the doors locked, knelt down and began to pray to God with such astonishing fervour and heartfelt heavenly eloquence, that the two poor wretches who were in the room did not dare to speak to him, and at last themselves left him and gave him a way to escape.

His virginal purity shone out of his countenance. His eyes were so clear and bright, even to the last years of his life, that no painter ever succeeded in giving the expression of them, and it was not easy for anyone to keep looking on him for any length of time, for he dazzled them like an Angel of Paradise.

Moreover, his body, even in his old age, emitted a fragrance which, even in his decrepit old age, refreshed those who came near him; and many said that they felt devotion infused into them by the mere smell of his hands.

As to the opposite vice. The ill odour of it was not to the Saint a mere figure of speech, but a reality, so that he could detect those whose souls were blackened by it; and he used to say that it was so horrible that nothing in the world could equal it, nothing, in short, but the Evil Spirit himself. Before his penitents began their confession he sometimes said, “O my son, I know your sins already.”

Many confessed that they were at once delivered from temptations by his merely laying his hands on their heads. The very mention of his name had a power of shielding from Satan those who were assailed by his fiery darts.

He exhorted men never to trust themselves, whatever experience they might have of themselves, or however long their habits of virtue.

He used to say that humility was the true guard of chastity; and that not to have pity for another in such cases was a forerunner of a speedy fall in ourselves; and that when he found a man censorious, and secure of himself, and without fear, he gave him up for lost.

Prayer

PHILIP, my glorious Patron, who didst ever keep unsullied the white lily of thy purity, with such jealous care that the majesty of this fair virtue beamed from thine eyes, shone in thy hands, and was fragrant in thy breath, obtain for me that gift from the Holy Ghost, that neither the words nor the example of sinners may ever make any impression on my soul. And, since it is by avoiding occasions of sin, by prayer, by keeping myself employed, and by the frequent use of the Sacraments that my dread enemy must be subdued, gain for me the grace to persevere in these necessary observances.

Prayer of Cardinal Baronius (above)

Day 5: Philip’s Tenderness of Heart

St. Philip Neri and Pope Clement VIII. (Source).

Philip could not endure the very sight of suffering; and though he abhorred riches, he always wished to have money to give in alms.

He could not bear to see children scantily clothed, and did all he could to get new clothes for them.

Oppressed and suffering innocence troubled him especially; when a Roman gentleman was falsely accused of having been the death of a man, and was imprisoned, he went so far as to put his cause before the Pope, and obtained his liberation.

A priest was accused by some powerful persons, and was likely to suffer in consequence. Philip took up his cause with such warmth that he established his innocence before the public.

Another time, hearing of some gipsies who had been unjustly condemned to hard labour, he went to the Pope, and procured their freedom. His love of justice was as great as his tenderness and compassion.

Soon after he became a Priest there was a severe famine in Rome, and six loaves were sent to him as a present. Knowing that there was in the same house a poor foreigner suffering from want of food, he gave them all to him, and had for the first day nothing but olives to eat.

Philip had a special tenderness towards artisans, and those who had a difficulty of selling their goods. There were two watchmakers, skilful artists, but old and burdened with large families. He gave them a large order for watches, and contrived to sell them among his friends.

His zeal and liberality specially shone forth towards poor girls. He provided for them when they had no other means of provision. He found marriage dowries for some of them; to others he gave what was sufficient to gain their admittance into convents.

He was particularly good to prisoners, to whom he sent money several times in the week.

He set no limits to his affection for the shrinking and bashful poor, and was more liberal in his alms towards them.

Poor students were another object of his special compassion; he provided them not only with food and clothing, but also with books for their studies. To aid one of them he sold all his own books.

He felt most keenly any kindness done to him, so that one of his friends said: “You could not make Philip a present without receiving another from him of double value.”

He was very tender towards brute animals. Seeing someone put his foot on a lizard, he cried out, “Cruel fellow! what has that poor animal done to you?”

Seeing a butcher wound a dog with one of his knives, he could not contain himself, and had great difficulty in keeping himself cool.

He could not bear the slightest cruelty to be shown to brute animals under any pretext whatever. If a bird came into the room, he would have the window opened that it might not be caught.

Prayer

Philip, my glorious Advocate, teach me to look at all I see around me after thy pattern as the creatures of God. Let me never forget that the same God who made me made the whole world, and all men and all animals that are in it. Gain me the grace to love all God’s works for God’s sake, and all men for the sake of my Lord and Saviour who has redeemed them by the Cross. And especially let me be tender and compassionate and loving towards all Christians, as my brethren in grace. And do thou, who on earth was so tender to all, be especially tender to us, and feel for us, bear with us in all our troubles, and gain for us from God, with whom thou dwellest in beatific light, all the aids necessary for bringing us safely to Him and to thee.

Prayer of Cardinal Baronius (above)

Day 6: Philip’s Cheerfulness

St. Philip and an angel. (Source)

Philip welcomed those who consulted him with singular benignity, and received them, though strangers, with as much affection as if he had been a long time expecting them. When he was called upon to be merry, he was merry; when he was called upon to feel sympathy with the distressed, he was equally ready.

Sometimes he left his prayers and went down to sport and banter with young men, and by this sweetness and condescension and playful conversation gained their souls.

He could not bear anyone to be downcast or pensive, because spirituality is always injured by it; but when he saw anyone grave and gloomy, he used to say, “Be merry.” He had a particular and marked leaning to cheerful persons.

At the same time he was a great enemy to anything like rudeness or foolery; for a buffooning spirit not only does not advance in religion, but roots out even what is already there.

One day he restored cheerfulness to Father Francesco Bernardi, of the Congregation, by simply asking him to run with him, saying, “Come now, let us have a run together.”

His penitents felt that joy at being in his room that they used to say, Philip’s room is not a room, but an earthly Paradise.

To others, to merely stand at the door of his room, without going in, was a release from all their troubles. Others recovered their lost peace of mind by simply looking Philip in the face. To dream of him was enough to comfort many. In a word, Philip was a perpetual refreshment to all those who were in perplexity and sadness.

No one ever saw Philip melancholy; those who went to him always found him with a cheerful and smiling countenance, yet mixed with gravity.

When he was ill he did not so much receive as impart consolation. He was never heard to change his voice, as invalids generally do, but spoke in the same sonorous tone as when he was well. Once, when the physicians had given him over, he said, with the Psalmist, “Paratus sum et non sum turbatus” (“I am ready, and am not troubled”). He received Extreme Unction four times, but with the same calm and joyous countenance.

Prayer

PHILIP, my glorious Advocate, who didst ever follow the precepts and example of the Apostle St. Paul in rejoicing always in all things, gain for me the grace of perfect resignation to God’s will, of indifference to matters of this world, and a constant sight of Heaven; so that I may never be disappointed at the Divine providences, never desponding, never sad, never fretful; that my countenance may always be open and cheerful, and my words kind and pleasant, as becomes those who, in whatever state of life they are, have the greatest of all goods, the favour of God and the prospect of eternal bliss.

Prayer of Cardinal Baronius (above)

Day 7: Philip’s Patience

St. Philip’s otherworldly spirituality was infused with a hard and cutting common sense. (Source).

Philip was for years and years the butt and laughing-stock of all the hangers-on of the great palaces of the nobility at Rome, who said all the bad of him that came into their heads, because they did not like to see a virtuous and conscientious man.

This sarcastic talk against him lasted for years and years; so that Rome was full of it, and through all the shops and counting-houses the idlers and evil livers did nothing but ridicule Philip.

When they fixed some calumny upon him, he did not take it in the least amiss, but with the greatest calmness contented himself with a simple smile.

Once a gentleman’s servant began to abuse him so insolently that a person of consideration, who witnessed the insult, was about to lay hands on him; but, when he saw with what gentleness and cheerfulness Philip took it, he restrained himself, and ever after counted Philip as a saint.

Sometimes his own spiritual children, and even those who lay under the greatest obligations to him, treated him as if he were a rude and foolish person; but he did not show any resentment.

Once, when he was Superior of the Congregation, one of his subjects snatched a letter out of his hand; but the saint took the affront with incomparable meekness, and neither in look, nor word, nor in gesture betrayed the slightest emotion.

Patience had so completely become a habit with him, that he was never seen in a passion. He checked the first movement of resentful feeling; his countenance calmed instantly, and he reassumed his usual modest smile.

Prayer

PHILIP, my holy Advocate, who didst bear persecution and calumny, pain and sickness, with so admirable a patience, gain for me the grace of true fortitude under all the trials of this life. Alas! how do I need patience! I shrink from every small inconvenience; I sicken under every light affliction; I fire up at every trifling contradiction; I fret and am cross at every little suffering of body. Gain for me the grace to enter with hearty good-will into all such crosses as I may receive day by day from my Heavenly Father. Let me imitate thee, as thou didst imitate my Lord and Saviour, that so, as thou hast attained heaven by thy calm endurance of bodily and mental pain, I too may attain the merit of patience, and the reward of life everlasting.

Prayer of Cardinal Baronius (above)

Day 8: Philip’s Care for the Salvation of Souls

St. Philip Neri’s flame-red chasuble is one of the hallmarks of his iconography, such as in this portrait by Guido Reni, 1619. (Source)

When he was a young priest, and had gathered about him a number of spiritual persons, his first wish was to go with them all to preach the gospel to the heathen of India, where St. Francis Xavier was engaged in his wonderful career—and he only gave up the idea in obedience to the holy men whom he consulted.

As to bad Christians at home, such extreme desire had he for their conversion, that even when he was old he took severe disciplines in their behalf, and wept for their sins as if they had been his own.

While a layman, he converted by one sermon thirty dissolute youths.

He was successful, under the grace of God, in bringing back almost an infinite number of sinners to the paths of holiness. Many at the hour of death cried out, “Blessed be the day when first I came to know Father Philip!” Others, “Father Philip draws souls to him as the magnet draws iron.”

With a view to the fulfilment of what he considered his special mission, he gave himself up entirely to hearing confessions, exclusive of every other employment. Before sunrise he had generally confessed a good number of penitents in his own room. He went down into the church at daybreak, and never left it till noon, except to say Mass. If no penitents came, he remained near his confessional, reading, saying office, or telling his beads. If he was at prayer, if at his meals, he at once broke off when his penitents came.

He never intermitted his hearing of confessions for any illness, unless the physician forbade it.

For the same reason he kept his room-door open, so that he was exposed to the view of everyone who passed it.

He had a particular anxiety about boys and young men. He was most anxious to have them always occupied, for he knew that idleness was the parent of every evil. Sometimes he made work for them, when he could not find any.

He let them make what noise they pleased about him, if in so doing he was keeping them from temptation. When a friend remonstrated with him for letting them so interfere with him, he made answer: “So long as they do not sin, they may chop wood upon my back.”

He was allowed by the Dominican Fathers to take out their novices for recreation. He used to delight to see them at their holiday meal. He used to say, “Eat, my sons, and do not scruple about it, for it makes me fat to watch you;” and then, when dinner was over, he made them sit in a ring around him, and told them the secrets of their hearts, and gave them good advice, and exhorted them to virtue.

He had a remarkable power of consoling the sick, and of delivering them from the temptations with which the devil assails them.

To his zeal for the conversion of souls, Philip always joined the exercise of corporal acts of mercy. He visited the sick in the hospitals, served them in all their necessities, made their beds, swept the floor round them, and gave them their meals.

Prayer

PHILIP, my holy Patron, who wast so careful for the souls of thy brethren, and especially of thy own people, when on earth, slack not thy care of them now, when thou art in heaven. Be with us, who are thy children and thy clients; and, with thy greater power with God, and with thy more intimate insight into our needs and our dangers, guide us along the path which leads to God and to thee. Be to us a good father; make our priests blameless and beyond reproach or scandal; make our children obedient, our youth prudent and chaste, our heads of families wise and gentle, our old people cheerful and fervent, and build us up, by thy powerful intercessions, in faith, hope, charity, and all virtues.

Prayer of Cardinal Baronius (above)

Day 9: Philip’s Miraculous Gifts

The veneration of St. Philip has spread around the world. (Source)

PHILIP’S great and solid virtues were crowned and adorned by the divine Majesty with various and extraordinary favours, which he in vain used every artifice, if possible, to hide.

It was the good-pleasure of God to enable him to penetrate His ineffable mysteries and to know His marvellous providences by means of ecstasies, raptures, and visions, which were of frequent occurrence during the whole of his life.

A friend going one morning to confession to him, on opening the door of his room softly, saw the Saint in the act of prayer, raised upon his feet, his eyes looking to heaven, his hands extended. He stood for a while watching him, and then going close to him spoke to him—but the saint did not perceive him at all. This state of abstraction continued about eight minutes longer; then he came to himself.

He had the consolation of seeing in vision the souls of many, especially of his friends and penitents, go to heaven. Indeed, those who were intimate with him held it for certain, that none of his spiritual children died without his being certified of the state of their souls.

Philip, both by his sanctity and experience, was able to discriminate between true and false visions. He was earnest in warning men against being deluded, which is very easy and probable.

Philip was especially eminent, even among saints, for his gifts of foretelling the future and reading the heart. The examples of these gifts which might be produced would fill volumes. He foretold the deaths of some; he foretold the recovery of others; he foretold the future course of others; he foretold the births of children to those who were childless; he foretold who would be the Popes before their election; he had the gift of seeing things at a distance; and he knew what was going on in the minds of his penitents and others around him.

He knew whether his penitents had said their prayers, and for how long they were praying. Many of them when talking together, if led into any conversation which was dangerous or wrong, would say: “We must stop, for St. Philip will find it out.”

Once a woman came to him to confession, when in reality she wished to get an alms. He said to her: “In God’s name, good woman, go away; there is no bread for you”—and nothing could induce him to hear her confession.

A man who went to confess to him did not speak, but began to tremble, and when asked, said, “I am ashamed,” for he had committed a most grievous sin. Philip said gently: “Do not be afraid; I will tell you what it was”—and, to the penitent’s great astonishment, he told him.

Such instances are innumerable. There was not one person intimate with Philip who did not affirm that he knew the secrets of the heart most marvellously.

He was almost equally marvellous in his power of healing and restoring to health. He relieved pain by the touch of his hand and the sign of the Cross. And in the same way he cured diseases instantaneously—at other times by his prayers—at other times he commanded the diseases to depart.

This gift was so well known that sick persons got possession of his clothes, his shoes, the cuttings of his hair, and God wrought cures by means of them.

Prayer

PHILIP, my holy Patron, the wounds and diseases of my soul are greater than bodily ones, and are beyond thy curing, even with thy supernatural power. I know that my Almighty Lord reserves in His own hands the recovery of the soul from death, and the healing of all its maladies. But thou canst do more for our souls by thy prayers now, my dear Saint, than thou didst for the bodies of those who applied to thee when thou wast upon earth. Pray for me, that the Divine Physician of the soul, Who alone reads my heart thoroughly, may cleanse it thoroughly, and that I and all who are dear to me may be cleansed from all our sins; and, since we must die, one and all, that we may die, as thou didst, in the grace and love of God, and with the assurance, like thee, of eternal life.

Prayer of Cardinal Baronius (above)

St. Philip Neri, remember thy congregation. (Source)

Collect for the Feast of St. Philip Neri

O God, who never cease to bestow the glory of holiness

on the faithful servants you raise up for yourself,

graciously grant

that the Holy Spirit may kindle in us that fire

with which he wonderfully filled

the heart of Saint Philip Neri.

Through our Lord Jesus Christ, your Son,

who lives and reigns with you in the unity of the Holy Spirit,

one God, for ever and ever.

(Collect for the Feast of St. Philip)

Newman’s Litany to St. Philip Neri

(source)

A stained glass depiction. (Source)

Lord, have mercy.

Lord, have mercy.

Christ, have mercy.

Christ, have mercy.

Lord, have mercy.

Lord, have mercy.

Christ, hear us.

Christ, graciously hear us.

God the Father of Heaven,

Have mercy on us.

God the Son, Redeemer of the world,

Have mercy on us.

God the Holy Spirit,

Have mercy on us.

Holy Trinity, One God,

Have mercy on us.

St. Philip with (l-r): St. Ignatius Loyola, St. Francis Xavier, St. Teresa of Avila, and St. Isidore the Farmer. All five were canonized on the same day in 1622. The people of Rome said that, on that day, the Church canonized “Four Spaniards and a Saint.” (Source).

Holy Mary,

pray for us.

Holy Mother of God,

pray for us.

Holy Virgin of Virgins, etc.

Saint Philip,

Vessel of the Holy Spirit,

Child of Mary,

Apostle of Rome,

Counselor of Popes,

Voice of Prophecy,

Man of Primitive Times,

Winning Saint,

Hidden Hero,

Sweetest of Fathers,

Martyr of Charity,

Heart of Fire,

Discerner of Spirits,

Choicest of Priests,

Mirror of the Divine Life,

Pattern of humility,

Example of Simplicity,

Light of Holy Joy,

Image of Childhood,

Picture of Old Age,

Director of Souls,

Gentle Guide of Youth,

Patron of thine Own,

“The Ecstasy of St. Philip Neri,” Gaetano Lapis, 1754. (Source)

Thou who observed chastity in thy youth,

Who sought Rome by Divine guidance,

Who hid so long in the catacombs,

Who received the Holy Spirit into thy heart,

Who experienced such wonderful ecstasies,

Who so lovingly served the little ones,

Who washed the feet of pilgrims,

Who ardently thirsted after martyrdom,

Who distributed the daily word of God,

Who turned so many hearts to God,

Who conversed so sweetly with Mary,

Who raised the dead,

Who set up thy houses in all lands,

Lamb of God, Who takest away the sins of the world,

Spare us, O Lord.

Lamb of God, Who takest away the sins of the world,

Graciously hear us, O Lord.

Lamb of God, Who takest away the sins of the world,

Have mercy on us.

Christ, hear us.

Christ, graciously hear us.

V. Remember thy congregation.

R. Which thou hast possessed from the beginning.

Let us Pray.

O God, Who hast exalted blessed Philip, Thy confessor, in the glory of Thy Saints, grant that, as we rejoice in his commemoration, so may we profit by the example of his virtues, through Christ Our Lord.

R. Amen.

“St. Philip Neri,” by contemporary artist Alvin Ong. Acrylic on wood. 2014. Commissioned by the Oxford Oratory. (Source)