A Christ in sunglasses is nailed to a papier-mâché cross. He is, in fact, not just Jesus, but also Macauley Culkin and Kurt Cobain at once, the triune victim of philistines and a squad of jackbooted, mocking Romans who are dressed as Ronald McDonald. A Xenomorphic version of the clown himself pops out of the hook-handed captain’s chest and fires a lazer at a bleeding-eyed Virgin in a red Wendy’s wig. The good thief is Bill Clinton on a confetti-colored cross. The titulus crucis has been replaced with a cardboard scroll that reads “King of the Cucks.” Before departing, the last fast-food fascist takes a selfie with the Cobain-Christ. And good old George Washington, Oculus Rift still clasped to his head, burns to a crisp in orgiastic entertainment as the virtual sacrifice concludes.

Was this an Ayahuasca trip, a mystic hallucination, or a rather heavy-handed SNL skit?

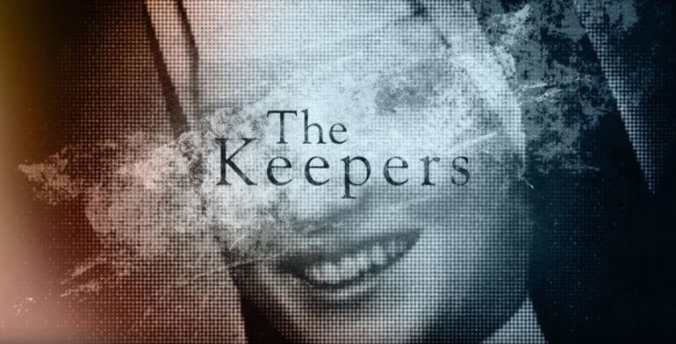

The answer, of course, is D, none of the above. It’s just another Father John Misty video. This one is entitled “Total Entertainment Forever,” and the track comes from his new release from Sub Pop, Pure Comedy. Father John Misty (alias Josh Tillman) has long produced a body of work at once blasphemous and baffling, though occasionally given to brief bursts of beauty. There is less of this latter quality in his newest album, and it’s sorely missed. Tillman has instead given us a project bloated with its own sense of self-importance and suffocating on its own shallow satirical spite.

Of course, it’s perfectly fine for an artist to mock, to rally, or to critique. Some of the greatest art does all three at once. Take, for instance, that modernist monolith, The Waste Land. T.S. Eliot may have contended for years that it was just “the relief of a personal and wholly insignificant grouse against life…just a piece of rhythmical grumbling,” but critics of every generation have recognized in the poem a powerful diagnosis of the sickness of Western civilization. Much of Eliot’s “grouse” remains relevant today, in part because, even as he pilloried all kinds of people, he grounded his art in the perennial images of human culture.

Father John Misty, alas, does not. He is content to complain without saying anything all that deep, and without investing his work with the kind of symbolic depth we recognize in Eliot.

The titular track, “Pure Comedy,” sets the mood for the rest of the album. We might as well spend some time looking at the lyrics. They reveal quite a lot about Father John Misty’s priorities and self-perception. Here are the first lines:

The comedy of man starts like this

Our brains are way too big for our mothers’ hips

And so Nature, she divines this alternative

We emerged half-formed and hope that whoever greets us on the other end

Is kind enough to fill us in

And, babies, that’s pretty much how it’s been ever since

The song goes on to announce that mankind’s lot is really just,

Comedy, now that’s what I call pure comedy.

Just waiting until the part where they start to believe

They’re at the center of everything

And some all-powerful being endowed this horror show with meaning

That right there is the little light in the plane that tells us to buckle up and get ready for the hackneyed atheist bits.

Oh, their religions are the best

They worship themselves yet they’re totally obsessed

With risen zombies, celestial virgins, magic tricks, these unbelievable outfits

And they get terribly upset

When you question their sacred texts

Written by woman-hating epileptics

For those of you who didn’t watch the video I linked above, let me save you some time. He’s not talking about Islam and Judaism. Tilman is mainly targeting Catholicism, even if he refrains from becoming explicit about it in the lyrics. Worse, he’s not even terribly original. The verse just distills the common, fedora-tipping New (c. 2006) Atheism of the Internet. Josh Tilman is no Ivan Karamazov.

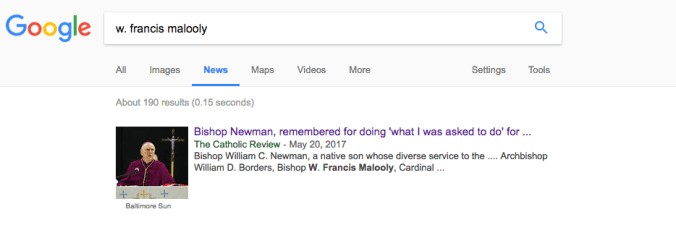

Tillman has shown a longstanding interest in religious themes, as his previous two album covers demonstrate. He is known to sprinkle his songs with religious allusions. Pure Comedy features a track entitled “When the God of Love Returns There’ll Be Hell to Pay.” Tillman sings about what he would tell Jesus as the Apocalypse unfolds. He says that he would give Jesus a tour of the world, then says:

Barely got through the prisons and stores

And the pale horse looks a little sick

Says, “Jesus, you didn’t leave a whole lot for me

If this isn’t hell already then tell me what the hell is?”

Tillman, never wary of blasphemy, says to Christ, “And now you’ve got the gall to judge us.” One might point out the irony of Tillman posing as a holier-than-thou moral authority when, just a few lines earlier, he equates prisons and stores. If this fatuous and fundamentally unserious judgment doesn’t betray a warped moral sensibility, then I’m not sure what does.

On a more philosophical note, let me say that it is the prerogative of the artist to explore the bounds of the possible, especially when crafting strange hypotheticals like the one that Tillman imagines. Tillman also works in a long tradition of artists who mediate their work through the careful deployment of personae. His stage-name, Father John Misty, is a good example of this tendency (and a religiously-tinged one at that). But even granting these stipulations about the nature of art, we should remember a third point. All art inherently crafts aesthetic experience and therefore “sets the stage” for a presentation and affective reception of beauty. Insofar as art is bound to beauty, it is necessarily tied to the good and the true as well. Art can deny, flatter, hide, contest, mask, or assail goodness and truth, but it can never be rid of them and their own proper criteria. The problems that arise when we try too hard to make art “good” or “true” are many and easy to identify. But we cannot totally separate the aesthetic world from the moral and scientific spheres of life. An artist whose work displays a perverse moral sensibility may produce great art, but it will be somewhat immoral, and it may not correspond to the way things really are.

Fear Fun (2012). A much better album. Note the religious imagery underneath all the chaos.

I Love You, Honeybear (2015). A not very good but still better album. Here, too, FJM appropriates Christian iconography.

But back to “Pure Comedy.”

Perhaps because his criticism of religion/Christianity is so stale, Tillman spices things up a bit in the next verse by trying to be Relevant© and Woke™. Even without watching the video, you can tell that it’s about a certain unsavory Head of State.

Their languages just serve to confuse them

Their confusion somehow makes them more sure

They build fortunes poisoning their offspring

And hand out prizes when someone patents the cure

Where did they find these goons they elected to rule them?

What makes these clowns they idolize so remarkable?

These mammals are hell-bent on fashioning new gods

So they can go on being godless animals

It’s not clear whether Tillman lost his faith in humanity because of Trump, or if the Donald’s ascent merely confirmed a longstanding pessimism. One could perhaps sympathize with the latter position, if only because it would be intellectually honest.

But I digress.

We come to the emotional climax of the song.

Oh comedy, their illusions they have no choice but to believe

Their horizons that just forever recede

And how’s this for irony, their idea of being free is a prison of beliefs

That they never ever have to leave

I would take his point more seriously if it were not a banal and adolescent bastardization of Camus or Rand or Nietzsche or [insert edgelord here]. “Pure Comedy” is not unique in this sense of immaturity. Listening and reading through all the songs, I was repeatedly reminded of angsty teenage poetry. Tillman’s unhappy tendency to be biographical, abstract, and preachy was not nearly as pronounced in his earlier work as Father John Misty (I can’t speak to his releases as J. Tillman).

Unfortunately, the song doesn’t get better from there. In the final verse, Tillman croons,

The only thing that seems to make them feel alive is the struggle to survive

But the only thing that they request is something to numb the pain with

Until there’s nothing human left

Just random matter suspended in the dark

I hate to say it, but each other’s all we got

The idea of our planet being nothing more than a rock in space comes up again and again throughout the album. At the beginning of one track, Tillman calls the earth “this bright blue marble orbited by trash.” It’s Eliot’s “Unreal City,” brought up to date for the space age. But in that last line, we hear the echoes of Auden’s famous poem about the beginning of World War II; “We must love one another or die.” It’s a maudlin sentiment that Auden repented for the rest of his life. One wonders if Tillman will someday look back on the shallow clichés of “Pure Comedy” with the same sense of regret.

The rest of the album continues these themes. Tillman gives us a tour of the imbecility of human nature, especially as manifested by the entertainment industry, pharmaceutical corporations, Republicans, fast food, the religious, Middle America, social media, public intellectuals, and ideologues of all sorts. By the end, the Holden Caulfield act gets old. In most of the songs, the music trundles along aimlessly, neither powerful nor novel enough to sustain Tilman’s puerile lyrics.

Democritus laughs because he sees that the world is hopeless. (Source).

All of which is a serious disappointment to someone like me, who’s been a fan for years. You see, this ain’t Father John Misty’s first rodeo in the American Wasteland. His earlier work often treated these same themes, but in a more aesthetically and intellectually sophisticated way. Where in Pure Comedy do we find a song that matches the sultry and haunting sense of doom rippling through “Funtimes in Babylon?” Or the perky, quirky, frenzied mania of “I’m Writing a Novel?” Or the languid malaise of “Bored in The USA?” Or the soulfully earnest and operatically desperate madman’s litany, “Holy Shit,” perhaps Tilman’s finest piece yet? All of these songs work, not just because of their evocative lyrics, but because they are genuine musical accomplishments. Each is a gem of a song in its own way. In each, Tillman flexes the considerable powers of his unique voice. His sound manages to swing seamlessly between a controlled vigor and a vulnerability that shines without brittleness.

The album is not without its strengths. The satire does sometimes land pretty well, as in “Birdie” and “Things It Would Have Been Helpful To Know Before the Revolution” and “Ballad of the Dying Man.” In “The Memo,” Tillman wields his well-refined sense of shock value to drive home an unremittingly cynical take on the entertainment and advertising industries. But perhaps I’m just gravitating to songs that are pretty clearly meant to mock the left establishment or deflate the pretensions of neoliberals and transhumanists.

In “Dying Man,” we hear:

So says the dying man once I’m in the box

Just think of all the overrated hacks running amok

And all of the pretentious, ignorant voices that will go unchecked

The homophobes, hipsters, and 1%

The false feminists he’d managed to detect

Oh, who will critique them once he’s left?

A nice bit of biting sarcasm there. But sadly, Tilman smothers his wit under clunky diction—a verbose, chatty mess apparently composed without any care for euphony. Paired with lackluster music, the song fails.

The only really superlative work in the entire album is Tillman’s flawless penultimate track, “So I’m Growing Old on Magic Mountain.” Here, too, he is commenting on the madness of our times. But he’s left aside the pose of the pontificating prophet. Gone are the grand and sweeping lines about “human nature” as in “When the God of Love Returns.” Gone, too, are the plastic, pop-culture in-jokes that masquerade as hot takes; gone, the pearl-clutching about the woes of consumerism and fast food and the stupid white people who vote Republican and believe in God.

Instead, Tillman tells a story. A New Year’s Eve party has just ended, and the revelry is fading away. One of the guests describes the scene.

That’s it. Observe:

The wine has all been emptied

And smoke has cleared

As people file back to the valley

On the last night of life’s party

These days the years thin till I can’t remember

Just what it feels like to be young forever

Tillman’s more symbolic and sensitive tack suits his message; our age echoes the cultural moment that led Thomas Mann to write The Magic Mountain, and coming to grips with that realization has aged us. His sonic scene-craft evokes universal images and elevates the song into a testament of the human condition. If Tilman intends to speak to our particular cultural moment in Pure Comedy, he succeeds with “Magic Mountain.”

The only real shame is that there weren’t more songs like it on the rest of the album.

Pure Comedy

Father John Misty, Sub Pop Records, 2017

5.5/10 stars.