St. John Damascene and the St. Virgin Tricherusa, Giovanni Gasparro. Here we see Gasparro depicting a legend from the Saint’s life that is particularly appropriate for an artist. The work also represents the unity of Western and Eastern visual traditions in the transcendent Divinity. (Source)

UPDATE 4/2/20: It has recently come to my attention that Giovanni Gasparro, the artist profiled here, whose work I have admired at this blog on several occasions, has just produced a painting that reproduces the vicious anti-Semitic trope of Jewish ritual murder. This lie has historically led to violence against the Jews and, to put it lightly, is a subject unbecoming of a Christian painter. I condemn it in the strongest possible terms. While I used to look to Mr. Gasparro as a prime example of what Christian art could be in our postmodern era, his embrace of imagery more fit for the pages of Der Stürmer means that I can no longer endorse him. Nevertheless, I have decided to keep this essay up online because it enunciates certain principles about art that I think remain important. I hope that my readers will understand that they reflect an assessment of Mr. Gasparro’s value as religious art that I no longer hold.

Recently there came into my newsfeed an article by Hilary White Obl.S.B. of What’s Up with Francischurch?. The piece was an extended criticism of Giovanni Gasparro, an Italian artist whose paintings inspired a few of the meditations I have written before on this blog. As someone who has long admired Mr. Gasparro’s Neo-Baroque art, I was happy to see that Rorate Caeli recently profiled one of his pieces. Ms. White was, it seems, partially responding to this attention. However, the more I read of her article, the more I found myself in stark disagreement with her analysis and broader philosophy.

While I have in the past appreciated her reporting as well as the monastic spirit she brings to her work, I confess that I was surprised at the poor quality of her post. I would not ordinarily seek out controversy, but as it seems that Ms. White’s post is making the rounds of the Tradisphere, I felt it imperative to offer a counter perspective.

There are many problems with the article. It is a textbook example of how not to write about art and theology, failing comprehensively at description, prescription, and imagination. She focuses too heavily on one work, Gasparro’s St. Pius X Pontifex Maximus. When she looks at other examples of his art, her analysis – if that is the right word for her summary denunciations – always remains far too cursory to do justice to such a talented artist. And while she notes that Gasparro is a master draughtsman, she follows up this comment with the presumptive assertion that Gasparro “is someone who still approaches sacred subjects with a distinctly modernist mindset.”

St. Pius X Pontifex Maximus, Giovanni Gasparro. (Source)

There are overarching philosophical problems with Ms. White’s argument. But I’d prefer to begin with her shoddy treatment of the material itself.

To start with a small, but, I think, a representative example; Ms. White claims that in Gasparro’s portrait of Pope St. Pius X, the light falls on the Pope’s face in a sinister way. She writes,

But the painting of Pius X is underlit, a type of lighting that we associate with evil. If you see horror movies, the light is often placed this way on a face to give it a frightening, even demonic effect. It’s what springs to mind: where does a light come from if it’s up from below? Still, is hell’s light this white, electric glare?

This effect, illuminating the facial structure from an odd and unnatural angle – light doesn’t usually come from the ground up, still less heavenly light – the underside of the brow ridge lit up, giving the eye sockets a sickly, sunken appearance, etc… None of that is going to be found in genuine devotional sacred art.

An interesting idea, but one that misses the mark.

For one thing, the Pope is not underlit. It would be more accurate to say that he’s side-lit. There is a striking similarity in the way the light falls in Gasparro’s piece and the photograph of St. Pius to which Ms. White compares it. Nor is side-lighting unusual in Catholic art. Zubarán’s famous St. Francis in Meditation (1635-39) uses almost exactly the same angle for a much more sinister effect.

Her rather contrived interpretation requires one of two presuppositions: first, that the symbolic lexicon of sacred, or, indeed, Western art is so narrow as to entail only a very limited range of connotations in the use of light, and secondly, that Gasparro’s work is intrinsically profane, deceptive, or downright evil. Neither of these assumptions is fair to the the artwork. They obscure its meaning rather than illuminate it.

But this point is relatively minor compared to some of Ms. White’s other egregious analysis. She dismisses Gasparro’s oeuvre as “surrealist, not sacred art,” with particular attention to his common motif of multiplied hands. She takes exception to the way he depicts faces, as well. Once again, we can see this tendency on display in her take on the Pius X portrait:

Giuseppe Sarto – even in death – had a very “beatific” face, handsome and always with a very assured and calm expression. I can’t imagine him ever making a face like the one in the painting. In fact, it looks more like what you’d get if you cloned Pius X and added a few drops of Nigel Farage.

She goes on to suggest that the “lumps and bumps” on the face of Gasparro’s Pius X are unsound, and that his expression inappropriately reflects “apprehension, not adoration.”

I’ll admit, the likeness is imperfect. She’s not totally off to note the resemblance with Nigel Farage, an unfortunate quality of the painting. Nevertheless, these indignant statements reflect more on Ms. White’s failure of imagination than they do Mr. Gasparro’s art. Moreover, mightn’t the Pope’s face also convey a whole range of emotions? Instead of apprehension, couldn’t the Pope’s expression show humble supplication? Or simply the holy Fear of God that priests ought to hold in their hearts as they offer the Most Holy Sacrifice of the Mass? And might not Pope Sarto have made much the same face at the altar as he spoke the sacred and secret words to the Almighty? Is she really incapable of imagining him “ever making a face like the one in the painting?” Sure it’s not that hard.

Ms. White continues in this vein at some length.

The “light” from the Eucharist isn’t actually light. It illuminates nothing, there is no reflection of it on the face or hands or vestments. The halo is equally dead as a light source, since it falls on nothing. The only light on the figure is from this lower left white source – like a stage light. The non-light from the Eucharist could be a signal; is he saying, “This is NOT the light of the world”?

One gets the impression that the message of the painting is that Eucharistic theology is deception; there is no light from the Host, the celebrant does not believe; his face says “this is all theatre & flummery”

In fact, the more you look at it, the more the feeling grows that this is actually a parody of sacred art. As a friend of mine commented, “His face in no way looks beatific.” There’s something in this hyperrealism, all the lumpiness and the harsh white lighting, that doesn’t say heavenly to me, but psychotic. They seem like subtle corruptions of reality.

What an extraordinary concatenation of assertions.

A few questions come to mind immediately. First, why must the Eucharist necessarily illumine anything? There are, of course, discernible rays of light emanating from it, and any ordinary viewer who sees the painting would probably understand what is meant spiritually. But why should that light be seen to rest on anything in particular, when it’s already an unearthly light to begin with? Secondly, why do halos need to be light sources at all? David Clayton has argued at New Liturgical Movement that:

…the art of the High Renaissance and Baroque is aiming to portray historical man (and not as with the icon eschatological man united with God in heaven), what the artists are doing might in fact be consistent with this. One might propose that because the aura of uncreated light, the nimbus, would not be as visible (to the same degree at any rate) in fallen man, even if that man is a saint. So it would seem that the artist might choose not to portray a halo very faintly, as a slight glow, or even not at all.

The Madonna Benois, Leonard da Vinci. One of the paintings to which Clayton draws our attention – note that the halos of both are just golden circles, not lights. (Source).

Clayton’s division between iconography and art is an important, to which we will return, in a certain sense, later. For now, I’ll merely note two facts: a) it is extraordinarily commonplace in Western art to find halos that don’t function as any kind of light source, and b) the halo in Gasparro’s painting of the Pope is a diffuse but definite illumination. I can’t help but feel I am looking at an altogether different image than Ms. White, based on how badly she has described it. Instead of attempting to determine what the artist is actually communicating with what he has shown, Ms. White has given us a testimony of her own reactions.

Where she does attend to the painting as such, she uses the overly suspicious hermeneutic of a conspiracy theorist. The least probable and most malignant of interpretations come to the fore. Instead of merely asserting, as she is free to do, that Gasparro has painted a bad bit of sacred art, she instead goes so far as to accuse the artist of parodying the sacred.

There may be something grotesque, kitschy, or even campy about Gasparro’s oeuvre. But the grotesque, kitsch, and camp are three typical Catholic idioms. Look at the little prints of the Sacred and Immaculate Hearts surrounded by roses of all colors, adored by angels in little white gowns. Look at the gargoyles that grow like frightful stone pimples from the corners of our Cathedral spires. Look at the contorted muscles and thorn-choked skin of the Isenheim Altarpiece. Look at the Rococo churches that dot the landscape of the old Hapsburg Lands. Look at the Spanish processions of Holy Week, with all those peaked hoods and gilt statues in the streets. Look for the buskins and buckles of the pre-conciliar clerics. Look at the huge folds of watered silk enshrouding cardinals and archbishops and all manner of monsignori in that more confident age of the Church’s triumph. Look indeed at the splendid choir dress of the Institute of Christ the King, Sovereign Priest in our day! Look at Cardinal Burke in his glorious cappa magna (incidentally, Gasparro has done a charming portrait of him, too).

There is something delightfully other, delightfully weird, delightfully over-the-top about our religion. And surely, all of this is meet and right. The priest is other. The Church is other, and should appear mad in a world gone mad. Flannery O’Connor (probably) said, “You shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you odd.” Whatever its actual provenance, I take this saying as a true maxim of Catholic life in the modern world. I don’t mind if our art reflects that tendency for the strange, even if it disturbs us a little. I would be more suspicious if it didn’t.

We are all of us living as strangers, both to the world and to heaven. Gasparro’s art confronts us with this quality of strangeness, throws it back in our face – and startles us. Good. The Gospel is a very startling tale indeed.

Torculus Christi. Mystic press with St. Gabriele dell’Addolorata and St. Gemma Galgani, Giovanni Gasparro. One of his more overtly weird pieces, but one that is deeply rooted in Catholic mystical and artistic tradition. (Source)

Moving on to a few of Ms. White’s other statements, we come to her distinction between surrealist and sacred art. I happen to be working on a piece right now that will argue that surrealism is an artistic movement that, purged of its original anticlerical animus, can open up plenty of new avenues for a specifically Catholic spiritual art. Indeed, there is already quite a corpus of work that we might reasonably call Catholic surrealism, and I hope to incorporate it into that argument. In the meantime, I refute her argument thus.

Ms. White also takes exception with Gasparro’s very common use of multiplied hands in his paintings. She writes in one of her more patronizing captions,

He seems to be really big into this creepy thing with the multiple floating hands. This is what I would call “schtick” and it is common among highly trained younger artists who think that having a schtick will get them brand-recognition.

This wholesale dismissal is maybe the worst part of the essay. Once again, it evinces a refusal to engage with what Mr. Gasparro has put on the canvas for our consideration, summarizing it tidily in order to condemn it tout court.

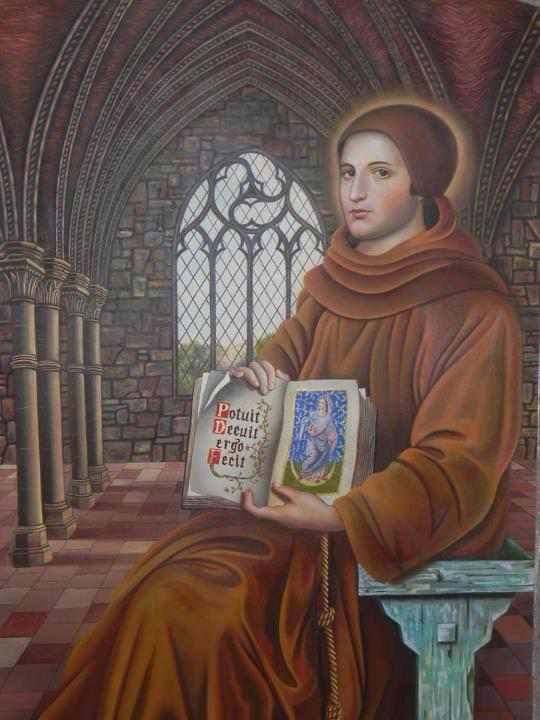

Gasparro’s multiplication of hands – or, in some cases, other body parts – serves two functions in his art. First, it can express the passing of time. In The Miracles of St. Francis of Paola (2015), the doubled set of hands represent discreet acts. Secondly, it can express numerous levels of spiritual meaning that otherwise might be missed through a more conventional image. Manipulating gesture opens up the image. This is particularly true in Gasparro’s Speculum Iustitiate (2014), St. Nicholas of Bari (2016), and his deeply moving portrait of Pius VII, Quum memoranda (Servant of God, Pope Pius VII Chiaramonti) (2014).

The doubling invites the viewer to consider each act or spiritual meaning in turn and to ponder how the subject may be acting in each case. The multiplication of hands invites us into a secondary, meditative dimension of the work. As I mentioned at the beginning of this essay, I have found his work a very fruitful spur to precisely this kind of spiritual meditation.

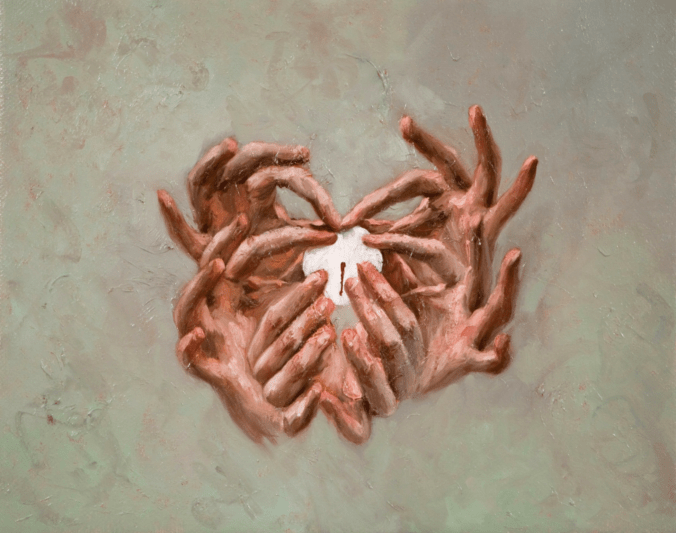

Take one of Gasparro’s finest pieces, Transunstanziazione (2009). I will repeat here what I wrote about it in my Corpus Christi piece:

Three pairs of hands, like the three pairs of wings on the seraphim and cherubim, bear aloft a bleeding host in undifferentiated space. The three sets of hands appear the same—they are, perhaps, the hands of the same priest captured over the lapse of time. This distortion of time and space lends the image a sense of eternity. We are viewing something transcendent. The Eucharist is not just an earthly event. It is also a rite which happens forever in the cosmic liturgy of heaven. And who is the Great High Priest offering that liturgy for us mortals? Who but Christ? In Gasparro’s image, Christ is present as priest and victim.

The three pairs of hands also remind us of the Trinity. When we approach the Eucharist, we truly approach the Triune God. At every Mass, the act of Transubstantiation only happens because of the work of the whole Trinity. Christ offers Himself to the Father in the Holy Spirit, through the hands of His priests and the prayer of His bride, the Church. It is meet and right that we should consider the painting at this point between the Ordinary Form celebrations of Trinity Sunday and Corpus Christi.

The painting has a certain sacramentality, in that, like the liturgy, it captures something of the invisible and manifests it to our earthbound senses. Looking at Gasparro’s painting, we have the sense that we are glimpsing something profound, unsettling, and sacred—something ordinarily hidden from us. Do we not hear the words of St. Thomas’s Corpus Christi hymn, Lauda Sion?

Every time I return to this painting, I find something deeper in it. I’ll add that the multiplication of hands is a trope that exists in the work of that most unimpeachable of Catholic Artists, the Blessed Fra Angelico, who uses it in virtually the same way as Gasparro.

The Mocking of Christ, Fra Angelico. Here he uses hands in the same ways that Gasparro does – to telescope sequential events into one image, to provide an insight into hidden action, and to lead us into meditation. Two of my Facebook friends noticed the formal and spiritual kinship between the two artists. (Source)

Of course, I don’t expect Ms. White or anyone else to have the same approach to every work of art as I do. If she finds Gasparro “creepy,” that is her right. But it is not an argument against Gasparro’s Catholicity. It is a subjective and affective assessment of his art, and thus it lies more in the realm of taste than aesthetic theology. And there’s nothing intrinsically wrong with having and describing a visceral reaction to a work of art. I’m perfectly happy to say de gustibus and leave it at that.

Unfortunately, Ms. White expatiates about what constitutes “sacred art,” which, she claims, is emphatically not what Mr. Gasparro is doing.

She writes,

Knowing nothing about him other than what he paints, I have no idea what this artist intends – and that right there should tell you that he’s NOT doing sacred art – but it seems that in general hyperrealism simply isn’t going to work for devotional art. It’s always going to come across as strange and parodic, because the purpose of devotional painting is not to depict ordinary earthly reality – with all its “warts” – but a supernaturalised, idealised and perfected reality, a redeemed reality, that can only be occasionally glimpsed in this life by seeing the saints.

Sacred art is devotional art. If it isn’t devotional, it’s a parody of the sacred.

Where do I begin?

First of all, it doesn’t matter what the artist intends. We emphatically don’t need to know the artist’s intentions to appreciate what exists in the constructed world of the art-object. It can be helpful, but it really isn’t necessary. “Intention” is one of those terms that is always so heterogeneous and slippery as to be virtually meaningless. Consider the range of “intentions” that might be implicit in any work of art. Most artists of the Renaissance probably intended to produce images that would please their wealthy patrons so that they could keep eating. Moreover, it seems that a great deal of eros generated quite a lot of the Western canon. No doubt at times the souls of the artists were illuminated by the grandeur of their work. But we can’t possibly know to what extent the deeply fallible men (and they were almost all men) intended to invest their work with a consciously spiritual meaning.

What’s more, Ms. White’s dislike for “hyperrealism” as well as “surrealism” leads her to miss the fact that Gasparro’s work strikes an incarnational balance between the two. His subjects are recognizably human, but in the strange art-world he depicts, they are charged with the heavy presence of a mystery far beyond their humanity. They share our condition while pointing towards a world that stands beyond it.

It bears mentioning that her dislike of “ordinary earthly reality – with all its ‘warts'” would necessarily strike Caravaggio from the canon of Catholic masters. Of course, Gasparro resembles Caravaggio more than any other artist. Perhaps she would be glad to see him go. Who else would disappear under Ms. White’s discriminating eye? Rubens and his corpulent maidens? Matthias Grunewald and his unpleasant crucifixions? How about Carlo Crivelli and the sly, malevolent eyes he gives to his saints? What are we to do with the Mannerists and all the distended limbs that litter their canvases? And although he was no Catholic, are we to write off the value of Rembrandt’s religious work because he dares to show the uneven surface of human flesh? Would this not be precisely the least Catholic impulse of all – to fly from the corporeality of our existence, and of the way God uses it?

Judith Beheading Holofernes, Caravaggio. This magnificent portrayal of Judith’s triumph over the wicked general is apparently not “sacred art” under Ms. White’s criteria. (Source)

Ms. White insists on idealism and devotionalism in sacred art. Anything that fails in either of these qualities must be consigned to the great heap of Modernist parody.

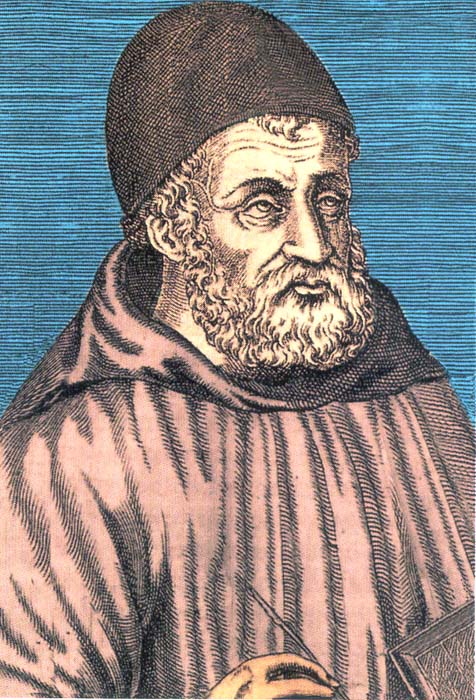

Yet both of these are deeply misbegotten efforts. First, when she speaks of “supernaturalised, idealised and perfected reality, a redeemed reality,” she is using the language of iconography. There is indeed much to commend the hallowed iconographic traditions of the Greeks and Slavs (not to mention the Armenians). But Byzantine icons are subject to strict canons, types, and lineages. An iconographer’s process and material are, to a certain extent, determined for him. Longstanding customs surround the production and ritual use of the icons. Part of the reason that theologians can work from the icons as a source in their writing is that those customs safeguard and guarantee the orthodoxy of the images. And the spirituality they have fostered over the centuries is one I admire; it has quickened my own Christian life.

The Most Chaste Heart of St. Joseph, Giovanni Gasparro. Something nigh-unprecedented like this devotional image would be impossible if Western art followed strict canons like the Byzantines do. (Source)

Nevertheless, that’s not what we do in the West. While some artists have managed to give us glimpses of a transcendent realm of sophianic glory (one thinks of the Cusco School and some of those Catholic surrealists I was talking about), they are certainly not obliged to do so by force of tradition. One can lament the fact that we developed a much freer sense of sacred art. I don’t, both because I like statues and because I think the relative freedom of artists has been an enormous boon to civilization and the Church.

We can definitely learn from icons, in part because they remind us of where our own tradition has been. Before this year’s terrible earthquake, Ms. White’s own monastery had a wonderful fresco that captured precisely this quality of enrichment from the East that can and should be productively pursued by Catholic artists. But we ought not make the spiritual vision of the East normative in the West, just as we would decry any effort to impose Western forms on the East. And so I entirely reject her attempt to foist on Western Catholic art the strict confines of the icons.

Secondly, I’m bothered by instrumentalist approaches to art, including an assessment that rests heavily on whether the piece in question is “edifying” or “devotional.” That’s a largely meaningless standard – much more indistinct than the question of whether something is beautiful – since it places the center of the art’s meaning and quality in the affective response of the viewer rather than its own constructed reality and the way that construction interacts with transcendental standards. Namely, beauty.

The idea that specifically sacred art should be a) “devotional,” and b) in a church is a narrow, limiting, overly contextual approach to art. It is only helpful in the strict sense of guidance for church decoration. If Ms. White had limited the purview of her argument to what should count as specifically Liturgical Art, that is, what type of art should be placed in a church for the public veneration and instruction of the faithful in a ritual context, she might have a point. But she doesn’t write within that important qualifier. Instead, she uses Mr. Gasparro’s oeuvre to think about sacred art in general, and arrives at the rather flattening dictum that “Sacred art is devotional art. If it isn’t devotional, it’s a parody of the sacred.”

Blessed Pius IX Pontifex Maximus, Giovanni Gasparro. Because artists who are really modernist heretics are drawn to depicting Pio Nono in prayer. (Source)

The conclusions she draws are totally unworkable as a Catholic approach to aesthetics. Imagine how much poetry and how much music we would have to surrender if we tried to carry the standards of idealism and devotionalism into the other arts in any kind of normative way.

Catholics should be concerned about the quality and orthodoxy of their sacred art. Insofar as Ms. White’s article represents that concern, it is an admirable effort. I’ll add that Ms. White and I probably share a similar exasperation with some of the trends in poor church art and architecture that are so maddening today. Likewise, we no doubt share a desire for a renewal of the Catholic arts. But Ms. White’s artistic philosophy smacks too much of Savonarola. While she is willing to summarily cast Gasparro’s art into the bonfire of the vanities, I contend that he is one of the Church’s most important living artists, alongside Daniel Mitsui, Matthew Alderman, Raúl Berzosa, Ken Woo, Alvin Ong, and others. I also share Rebecca Bratten Weiss’s views on the arts more broadly. We Catholics, and especially those of us who consider ourselves fairly Traditional, are sometimes too “self-referential” (if I may borrow a term favored by the Pope). As Weiss notes:

Toni Morrison, for instance, is a Catholic Nobel laureate whose works are filled with themes of community and redemption. But the Catholic critics who enthuse over Flannery O’Connor and Graham Greene regard Morrison only as a controversial writer on race relations. “She’s not practicing,” they might say, as an excuse to ignore her. And yet, C.S. Lewis, who is revered in their circles, was never even Catholic at all.

Mary Karr – the keynote speaker at the conference – not only is a Catholic convert, but wrote extensively about her conversion, but is deemed by some not to be a “real” Catholic writer, because of her openness about certain sexual issues. And yet Graham Greene was a notorious womanizer who slept with over 300 prostitutes, was condemned by church spokespersons in his time, and closed The End of the Affair with the prayer: “O God, You’ve done enough, You’ve robbed me of enough, I’m too tired and old to learn to love, leave me alone for ever.”

Perhaps the critics who are timid about these powerful Catholic writers working right now in our midst are waiting for someone else to “baptize” them? Perhaps they are waiting for someone else to say “I heard God there” – because they, themselves, have not learned to open the inner chambers of the ear? Because we do not have a robust Catholic arts culture that teaches us to open all the portals for reception, but instead have embraced a misnamed “Benedict Option” which is all about putting up walls and barriers, drawing those lines in the sand.

I concur, and would extend the same sort of criticism to Ms. White and those who support her view of the arts. Let us not fall into that old trap of mistaking the modern for Modernism. Christ is King over all. Let Catholic artists explore the plenitude of that Kingship over all, in all, and through all – even if looks strange to our worldly eyes.

Christ the King, Giovanni Gasparro. May we always serve Him with ardent charity and zeal for the beauty of His house. (Source)