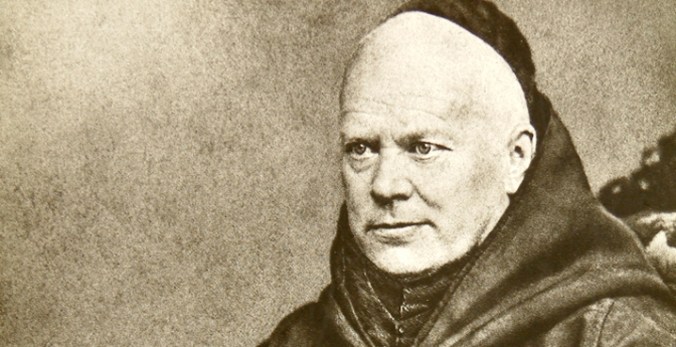

The Holy Face of Christ. (Source)

Dear Miriam,

Forgive me for my delay in replying to your message. You pose an excellent question, one that deserves an honest and well-considered answer. Indeed, I am not sure that I’m entirely qualified to speak on the matter. Not being a Biblical scholar, I can’t discuss the critical questions of authorship, Hebrew grammar, and culture that could be so useful. Alas. Nonetheless, I shall try to tell you what I understand the verse to mean, and why I saw fit to use it.

You ask me about what the Priestly Blessing means—especially what we are to understand by those mysterious words, “The Lord make his face shine upon thee, and be gracious unto thee: The Lord lift up his countenance upon thee, and give thee peace” (Numbers 6:25-26 KJV). You are right to note that there is something odd about this passage.

I believe the prayer is best understood through meditation. Let us look first at the beginning and bulk of the passage:

The Lord make his face shine upon thee, and be gracious unto thee: The Lord lift up his countenance upon thee…

What do we learn from these words? What does it mean to say, however poetically, that God has a “face,” a “countenance?”

First, it means that God is personal. The God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob is not an abstract, nameless force. He is not the Tao of the Chinese mystics—or not just that. Rather, He is someone, a who, an infinite yet utterly unique spirit. This truth entails another; God is relational. The face is the chief organ and sign by which we communicate with other people. The full range of our emotions find expression in the human face. The face becomes a symbol or synecdoche of our individual souls. It is the way we share our hearts. It is the bridge between our interiority and the other. Through speech, a kiss, an exchange of glances, the face mediates our personhood and thus becomes the location of communion.

The use of the word “countenance” in English sums up all these ideas, with one rather startling implication. God Almighty desires to be in a relationship with us. More than that, He wishes to dwell with us. The words of the blessing are not that of a God who will reign remotely. If the metaphor of the “face” suggests personality and relationship, it also suggests presence. God wants us to be wholly His, that He may be wholly ours. That is why He goes so far as to establish multiple, connected covenants with Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses, and David.

But covenants, like great love stories, are exclusive. You are right to point out the negative implication in the verse. If we pray for God to turn His face towards us, then surely God’s face could be turned away from us as well? I think the certain answer of the Bible, not to mention ordinary human experience, is yes. The ancient Israelites believed that they were a privileged, priestly people, subject to a totally unique relationship with God. Yet the whole of the Old Testament’s historical and prophetic corpus also shows that the Nation of Israel repeatedly caused God to “turn His face” away from them, not in loving them less, nor in breaching His covenant, but in permitting them to suffer chastisements that they might return to Him. The Holy only communes with the holy; God cannot abide with sin. And the Israelites often sinned. We all do. Speaking from my own life, I can testify that mortal sin is a terrible thing. To fall away from the face of God, to want to hide from His face as Adam did in the Garden, to feel Him turn His holy face away from you—such is the interior darkness and desolation wrought by sin.

Yet the ground of your question—why God’s face would be turned away from anyone— reveals that whether you realize it or not, you already have a basically Christian idea of God. To the ancient Jews who composed the Priestly Blessing for the liturgies of Tabernacle and Temple, the Face of God only turned towards the Nation of Israel. The idea that God loves all, and loves them unconditionally, is a notion that did not exist anywhere before the coming of Christ.

Indeed, the prayer receives its perfect answer and fulfillment when God takes on a human face. Jesus Christ is the Face of God, a divine person who wishes to be in an eternal and perfect communion with all men. That is why He is called Emmanuel, “God with us.” He is our eternal high priest (Hebrews 7:23-28; 9:11-14; 10:10-14).

And as our high priest, He has fulfilled the Priestly Blessing in three ways, all of which were unimaginable when it was written.

First, in His coming. In Christ, God has turned His face towards us—in the manger at Bethlehem, in His ministry among the poor and sick, in His companionship with sinners, in His Transfiguration, in His ceaseless prayer for us, in His cruel and unjust death upon the cross, and in His glorious Resurrection and Ascension.

Secondly, in the heart of the Godhead. By assuming human nature, God the Son becomes a human. By His Incarnation, Death, Resurrection, and Ascension into Heaven, He has brought a human face into the inner life of the Most Holy Trinity. God the Father gazes upon the human face of His Son, and He desires to see all mankind in and through that face. God the Spirit, eternal love, is born forth out of this mutual gaze. The Father and the Son only behold each other in the absolute love of the Spirit.

But what is the fruit for us today? The rest of the prayer tells us:

…and give thee peace.

Peace is not the absence of suffering, but the absence of disturbance. The peace of Christ, the peace “which passeth all understanding” is not to be taken as earthly ease and comfort (Philippians 4:7 KJV). That would merely be the false and facile peace of the world. The peace of God is a foretaste of Heaven, an inner rock upon which we may stand when suffering assails us, a seed of the Kingdom that may render us more perfect imitators of Christ. With the peace of God in our hearts, we may hope to know the true joy that, paradoxically, only grows from the cross. This peace is not a quiet meekness. It is the liberating freedom and security that comes from the knowledge of His love. Peace does not paralyze—it propels. It makes us undertake great adventures for God. Why? Because true peace is communion with God.

That is why I made use of the prayer at the end of my “Letter on Loneliness.” It occurred to me that the torment of loneliness is in some way redeemed if we remember the presence of the God who is love, and thus attain to His peace.

I don’t believe we can hope for the fullness of that peace without the sacraments, especially the Eucharist. It is simply impossible to be a Christian without the Eucharist. Any grace, any glory, any goodness in the world is only granted and sustained by Christ present with us in the Most Holy Sacrament of the Altar. Indeed, the graces of all the other sacraments flow from the Eucharist, since it is Christ Himself.

And it is in the Eucharist that we find the third way that Christ has fulfilled the Priestly Blessing and extended its meaning to all peoples and all epochs. In the Eucharist, we once again come face to face with the God of Israel—quite literally. His Eucharistic Face can be found in any Catholic Church on earth. Go to a service of Benediction. Chant hymns of adoration as the incense flies up like a ghost into the shadowy heights of the sanctuary. Let your soul rise with it, high above the little lights of the candles that line the altar. Then, as the bell rings and the priest lifts the Host, you will see God. Or at least, you will see His veil. He hides Himself under the sight of mere matter. No matter what, He will see you.

Better yet, go to Mass. Go to the Easter Vigil. Go on any Sunday. There, you will not only see God, but hundreds of perfectly ordinary people communing with Him in the most intimate way imaginable—body and soul. That holy act is the true fulfillment of the Priestly Blessing. It is the seal and crown of all the covenants. Not everyone in the world partakes of it—but happy are those who do! They alone know the Peace that was promised, the Peace that is He.

Forgive me if I have rambled. One could, in theory, write whole volumes on the verses you have asked me about. I am sure someone with more learning and a deeper life in Christ could give you an altogether better explanation. But what I have written is drawn ex corde meo. I hope, at the very least, that I’ve answered your question. I’d be happy to continue discussing the matter.

Until then, I pray that the Good Lord blesses you in all your works and ways.

In Christ,

Rick