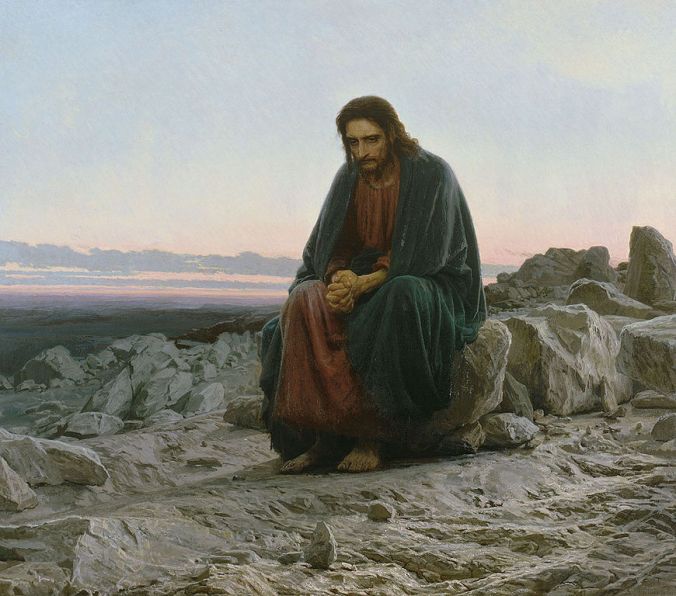

Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane, Veronese. Pinacoteca di Brera (Source)

My Dear Brother Josiah,

I received your last correspondence with a mixture of joy and sorrow. Joy, for all the good news you shared of our friends and familiars; sorrow, for those matters closer to your own heart that weigh so heavily upon your soul. Normally, I would not venture to offer unsolicited advice. However, as you have come to me seeking counsel, I will try to speak from what little light I have been granted. I will offer you, I hope, nothing but the constant teaching of the saints, nor anything I would not myself seek to follow. So much of what I must share is rooted in my own experience, the fruit of suffering not in all respects unlike your own.

You tell me that you worry about God’s blessing. You write that, in view of your griefs, you no longer trust that the Lord will bless you. This is a failure of Christian hope, but an understandable one. Faced with one reversal after another, it is easy to despair. I will point you first to the book of Job, a well from whose water I know you have already imbibed in more bitter times. What else could I tell you? The key practical thing is to recollect often those graces you have received. Savor them. Go over each, holding them close to your heart in memory. Make space in your week – better yet, your day – to ponder the grand and little mercies of God. I commend to you one of the very greatest pieces of wisdom I have received, that “a grace remembered is a grace renewed.” Continual recollection means that we are never really bereft of those graces once delivered unto us.

Look over your current state of life. The world, at least, sees your success. Many would desire your place. Thank God for what He has seen fit to give you so far.

But I know how incomparably small all of those worldly triumphs seem next to the losses you’ve suffered. I see what you mean when you say that you don’t trust God to bless you anymore. You aren’t speaking of those tangible blessings the world prizes in its vanity. You speak instead of the love of those taken from you. That golden blessing is worth all the others combined.

And so, we come to what seems to me to be the basic problem; not despair, but loneliness. The chill that stains even the brightest happiness and reveals the joys of this world to be fool’s gold. Have you considered loneliness in itself? Perhaps you have. It is a dark and loathsome thing. Perhaps you have found it buried down in your soul. A void. A hole that, like a carious tooth, aches and aches until it cries out for your full attention. A little black space at the bottom of things. You carry it around with you and never set it down. Grief carved it out, shaped it to its own image, and colors it even today.

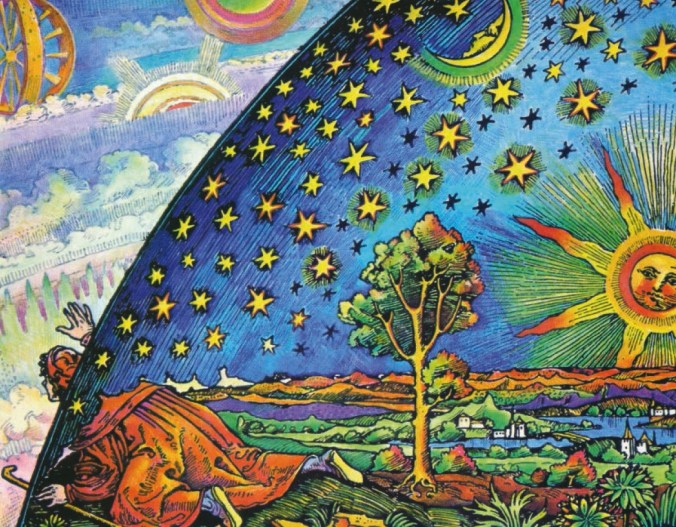

I don’t know if you will always bear that burden. Some of us must. But I would encourage you to embrace it. That emptiness is, in the words of R.S. Thomas, “a vacuum he may not abhor.” Come close to the void. Peer at it. Ecce lignum crucis! It is the cross you have been given. Fasten your heart to its center with the very nails of Our Lord’s passion. Accept His invitation, and you will be able to endure those long and painful hours when hope fails. One day, when you are least expecting it, something may very well happen. You may be at prayer in your room. You may be savoring the Eucharist at Mass. You may be finishing the sorrowful mysteries of the rosary. But suddenly, unbidden, the Holy Ghost will visit you. The darkness will turn to dazzling light. By some strange alchemy known only in heaven, the emptiness will all at once turn into a full fountain of molten gold. The cavern will become a cup that runneth over. The silence will become song beyond sound or human voice. And your heart will be seized by the beautiful and terrifying realization that the Living God sees you. If only for a moment, you will know what it is to be “alone with the Alone.” Then will your heart become one with His. Then will you know a communion that obliterates all loneliness and a joy that erases all grief.

This moment cannot be rushed. God will not come but in His own way and in His own time. All the same, one can prepare.

First and foremost, take your loneliness and grief to the sacraments. When you are at the offertory or some other convenient point at the Mass, give your heart to the Eucharistic Christ. Ask to be alone with Him in the Tabernacle. Cleave to it as to the one rock of safety in a stormy sea. Consider, too, how Our Lord suffers loneliness in the Tabernacle. Think how He is neglected in His tabernacles through all the world. Think how He desires your consolation – yours! Truly, He wishes to make that emptiness in your soul His true and everlasting Tabernacle. Will you deny your Lord? For in the Tabernacle, He is at once most suffering and most glorious. So, too, where you are most suffering, He will render you most glorious.

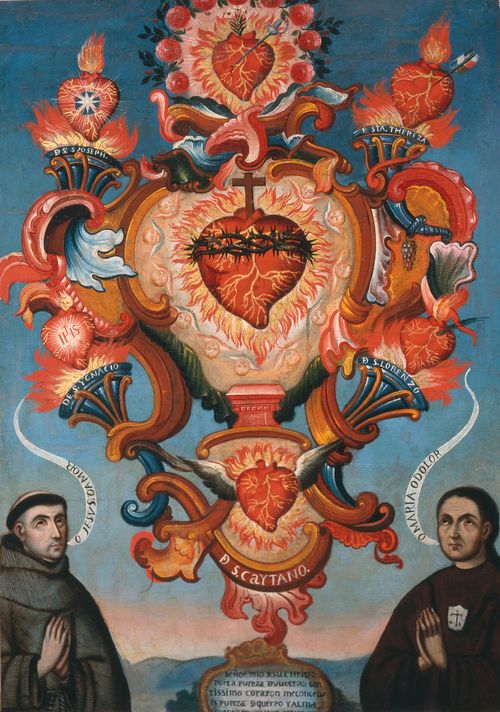

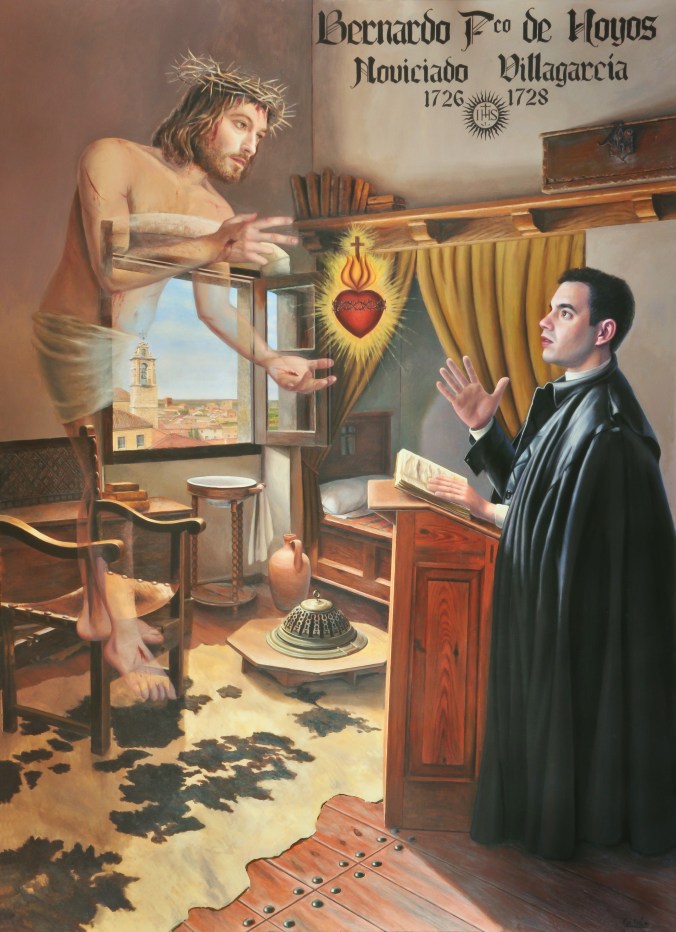

Second, make a point of consciously drawing near to Christ crucified in your daily prayer. One thing I’ve done in the past – though, I confess, I have lately been lax about it – is to pray the Divine Mercy chaplet and dedicate each decade to one of the Holy Wounds. Start by contemplating Our Lord’s feet, His physical presence on Earth during His lifetime and evermore in the Eucharist. Consider His comings and goings, and how He willingly ceases all of that to offer Himself to the Father on the cross. Then consider His left hand, the Kingly hand that holds the orb of the world. Ponder the ways of His Providence. Take heart in His mercy towards the penitent and His just judgment of the wicked. Praise Him for His true and final victory over the forces of evil, for scattering the proud in their conceit. Then, move to His right hand, the Priestly hand of blessing. Think of how He has transformed all things by the peace wrought with His right hand, under the sign of His blessing. Look forward to the world as it shall be on the day of His Wisdom’s Triumph. It is a world we can already enter at the Mass. Bring your gaze up to the Holy Face, wounded by the crown of thorns. Offer him your anxieties, your fears for the future, and all those worries that come from not knowing what you must do or why some calamity has transpired. Consider the crown of thorns as the mortification of your very reason. As Our Lord unquestioningly accepted the will of His Father, may you do the same. But remember to gaze into the Holy Face as into the very countenance of the Living God. Ponder Jesus Christ in His humanity. God is a person; nor is he just any person, but a person who suffered all that we suffer, and more. Finally, move to the wound in the Holy Side and the Sacred Heart. Give yourself up to as pure an expression of love for your Savior as you can muster. Consider the flood of water and blood that fell from those triumphant gates, so rudely torn open. Think, if you can, of the power so much as one drop of either precious liquid would have to redeem not just one soul, but millions and millions of universes teeming with the souls of the very worst sinners. Ponder what it means that you may receive the Precious Blood at even a low Mass. Fix your gaze beyond the Holy Side, passing into the darkness of Our Lord’s chest. Dwell upon the Sacred Hear in its quiet and eternal radiance. Know that Our Lord’s chest cavity is so very much like the void to which I have already alluded, and so like the Tabernacle. For in both, we find the Heart of God! Imagine yourself receiving the Sacred Heart in the Eucharist. Meditate upon the immense fire of Love pulsing there until the last shudder of death – and, as you come to the Trisagion, recall how that love blazed forth again on Easter Morn, never to be extinguished.

Third, keep in mind the words of St. Philip Neri. Amare Nesciri – “Love to be unknown.” One thinks of St. Benedict. In his rule, St. Benedict enjoins his children to overcome the temptations of lust with a similarly simple phrase, “Love chastity” (RB IV). St. Philip’s words carry many meanings. They are a wonderful program of humility, of perfection, of freedom, but also of loneliness and grief. Love to be unknown. Find God in the moment when no one else notices you. Don’t do what you do to be recognized, as the Scribes and Pharisees (Matt. 6:3, 16, Luke 18:9-14). Be content that God sees and knows you. It will take time to grow into this practice, but you will come to recognize its benefit. You may someday find someone to share or alleviate the yoke of your sorrows – maybe even someone to love. But until then, embrace Solitude as St. Benedict would have us embrace Chastity; that is, as a beloved spouse. Focus on that task, the one you have been given for now, and the rest will come to you as God sees fit in His own time. I would wager that it will make you happier and help you love others more perfectly.

Fourth, do not depart from under Mary’s mantle. If you wish to see the very picture of loss, I will show you the woman who, though the only one free of sin among the whole human race, suffered the loss of her parents, her husband, and her son. Turn your eyes to Mary. The sorrows of her Immaculate Heart demand your attention. We have no greater advocate and comfort in our own suffering than Mary, in union with her eternal spouse, the Paraclete.

Finally – hardest of all – you must forgive. Jesus’s death was not just a perfect sacrifice because He was an innocent and willing victim. He forgave His murderers. If we are to have a share in that death, we must learn the extremely difficult discipline of forgiveness. It is the only way we can be truly free.

I would be remiss in giving you these counsels if I did not add with all due caution that, insofar as any of it applies to me, I often fail. But I feel no shame in saying so, since Our Lord is magnified in weakness. Don’t rely only on my words, narrow and feeble as they are. If anything I have said is contradicted by the example of the saints and the teaching of God’s holy Church, refer to their superior model. After all, I’m not a priest. I’m not even all that well versed in theology. Seek out a spiritual father who can help your soul more intimately than a friend can.

For all that, be assured of my prayers and affection. I hope you find the hope that can only come from the Lord, my dear brother. May He bless you and keep you, and make His face shine upon you, and be gracious to you; may He turn His countenance upon you, and give you peace.

In Christ,

RTY