The Ascension fresco at Queen’s College Chapel, Oxford – perhaps my favorite chapel in the entire University. Photo by Fr. Lawrence Lew OP. (Source)

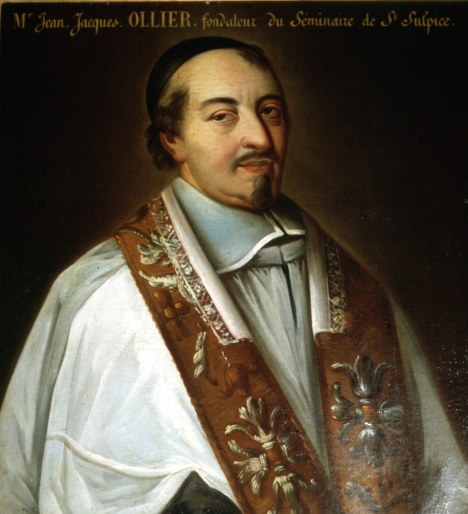

One of the greatest luminaries of the French Church in the 17th century, that period known as the Grand Siècle, was Jean-Jacques Olier. Though barely read today, he exerted a profound influence upon the formation of the French School of Spirituality through his work in founding the Sulpician Order. He was a close associate of St. Vincent de Paul, who always regarded him as a saint.

M. Olier, priez pour nous! (Source)

I have excerpted here his short chapter on the Ascension from his book, The Interior Life of the Most Holy Virgin. I must ask my readers to forgive me for not translating this edifying work, as I did not have the time. Those with French, however, will appreciate the depth of M. Olier’s insight.

***

Le sacrifice de Jésus-Christ étant offert pour l’Église, qui est visible, devait être visible lui-même dans toutes ses parties, afin de nous donner une certitude parfaite de notre réconciliation avec Dieu. Marie, dans le jour de la Purification, avait paru à l’offrande de la victime, en présentant elle-même, au nom de l’Église, Jésus-Christ notre hostie, et en le dévouant à l’immolation. Elle avait aussi été présente à la deuxième partie du sacrifice, à l’immolation réelle de Jésus-Christ sur la croix. La troisième, qui était la consommation ou le transport de la victime en Dieu, avait eu lieu dans le mystère de la Résurrection. Mais cette consommation s’était opérée d’une manière invisible; et la bonté de Dieu voulait que, pour notre consolation, cette partie du sacrifice devînt visible aussi bien que les deux autres, ou plutôt que Notre-Seigneur montât au ciel pour aller se perdre dans le sein de Dieu non-seulement à la vue de la très-sainte Vierge sa mère, mais encore sous les yeux de tous les apôtres par qui l’Église était représentée. C’est ce qu’avait figuré autrefois Élie montant au ciel dans un char de feu à la vue d’Élisée ; et ce prophète avait déclaré expressément à son disciple que, s’il le voyait monter, il aurait son double esprit. Don mystérieux, qui exprimait le fruit du sacrifice, c’est-à-dire l’esprit de mort et de résurrection ou de vie divine, que Jésus-Christ devait laisser à l’Église figurée par Élisée.

Après sa résurrection, il communiquait toutes les dispositions et tous les sentiments de son âme à sa bénite Mère. Il lui exprimait spécialement les désirs ardents qui le pressaient d’aller enfin se réunir à Dieu son Père, pour le louer et le glorifier dans le ciel. Marie, de son côté, éprouvait un véhément désir d’y accompagner son Fils, pour s’unir à ses louanges; et sans doute qu’elle eût terminé alors sa vie et l’eût suivi dans les cieux, s’il n’eût voulu se servir d’elle pour aider l’Église dans ses commencements.

L’oeuvre de cette divine Mère était encore incomplète. Après avoir donné, par Marie, naissance au chef, Dieu voulait procurer aussi, par elle, la formation de tout le corps. Il voulait la rendre mère de sa famille entière, de Jésus-Christ et de tous ses enfants d’adoption. Par zèle pour la gloire de Dieu et par charité pour nous, elle accepte avec joie la commission que Notre-Seigneur lui laisse de travailler à faire honorer son Père par les hommes, et de demeurer sur la terre jusqu’à ce que l’Église ait été bien affermie.

Le quarantième jour après la Résurrection étant donc venu, Jésus-Christ- se rend à Béthanie avec sa sainte Mère et ses apôtres; là élevant les mains et les bénissant, il se sépare d’eux, et en leur présence s’élève vers le ciel. Ils l’y suivirent des yeux, jusqu’à ce qu’enfin une nuée le dérobe à leur vue; et comme néanmoins ils tenaient toujours leurs regards fixés au ciel, deux anges vêtus de blanc leur apparurent et leur dirent : Pourquoi vous arrêtez-vous à regarder le ciel? Ce Jésus, qui a été attiré du milieu de vous dans le ciel, viendra de la même manière que vous l’avez vu monter au ciel. Ainsi Dieu voulut-il que l’acceptation solennelle qu’il faisait de notre hostie, eût pour témoins non-seulement tous les apôtres et la très-sainte Vierge, qui l’avait produite de sa propre substance, mais les anges eux-mêmes.

En montant dans les cieux, Jésus-Christ élève avec lui tous les saints patriarches et les autres justes qu’il avait retirés des limbes, et va les offrir à son Père, comme les premières dépouilles qu’il a ravies au démon par sa mort. Enfin, dérobé par la nuée à la vue de ses disciples, il laisse rejaillir la splendeur de sa gloire, qu’ils n’auraient pu soutenir et dont il avait retenu l’éclat dans ses diverses apparitions.

Comme les enfants des rois donnent des présents à leurs sujets, en faisant leur entrée dans leur royaume, Jésus-Christ, montant à la droite de son Père pour prendre possession de son trône, voulait envoyer à ses apôtres son esprit et ses dons, c’est-à-dire dilater son coeur en faisant entrer les hommes dans ses sentiments de religion envers Dieu son Père, et achever ainsi son ouvrage. Dans ce dessein et par son commandement, les disciples s’assemblèrent à Jérusalem avec la très-sainte Vierge et plusieurs saintes femmes; et là ils étaient en prière, louant, bénissant le nom de Dieu, et attendant la venue de l’Esprit-Saint. Marie était au milieu d’eux et présidait ce sacré concile, comme ayant, pour aviser à établir la gloire de Dieu dans le monde, une grâce qui excellait par-dessus celle de tous les apôtres. Quoique Jésus-Christ n’eût pas voulu qu’elle fût présente à la Cène, ni qu’elle offrît extérieurement le saint sacrifice, ni qu’elle fût prêtre selon l’ordre de Melchisédech, il voulait néanmoins que Marie, destinée à être la mère des vivants, se trouvât dans le Cénacle avec les apôtres, afin de verser la plénitude de son esprit en elle, comme dans le réservoir de la vie divine, et de la distribuer par elle à tous ses enfants, et aussi pour apprendre à l’Église que jamais elle ne serait renouvelée qu’en la société de sa divine Mère et en participant à son esprit.

A rococo altar depicting the Ascension, Ottobeuren, Germany. (Source)

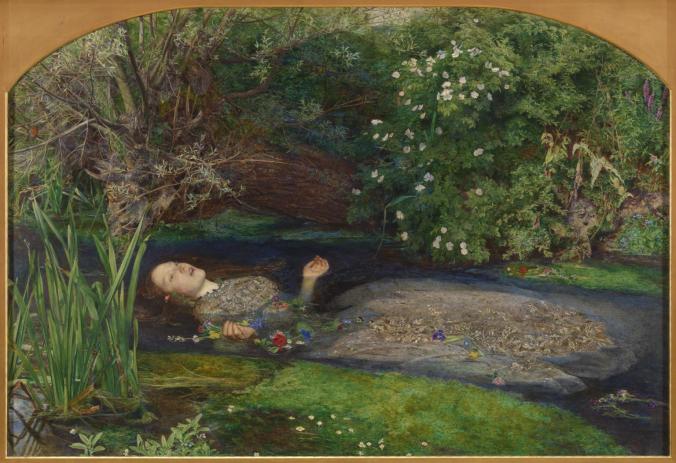

If you’re not just lying about languidly in a meadow, you’re not really doing it right, are you?

If you’re not just lying about languidly in a meadow, you’re not really doing it right, are you? It is also acceptable to lie there with an audience, preferably one enjoying a lovely picnic. And everyone must be the same gender and should, if at all possible, be dressed in very uncomfortable clothing.

It is also acceptable to lie there with an audience, preferably one enjoying a lovely picnic. And everyone must be the same gender and should, if at all possible, be dressed in very uncomfortable clothing.

And of course, you should be arrayed in an artfully disheveled white dress. To get that shabby chic look, you know?

And of course, you should be arrayed in an artfully disheveled white dress. To get that shabby chic look, you know? How you dishevel it is up to you.

How you dishevel it is up to you.